A sideways look at economics

Some years ago, when I was single, I met a girl in a bar. We exchanged numbers and agreed to go on a date. In one of our pre-date text conversations, I told her that I hated emojis. She told me that she loved emojis. There was an awkward pause. We never went on the date. Scroll forward several years and things have changed: not only am I now in a happy, stable relationship, but I have slowly, and reluctantly, accepted emojis into my life. 😊

My position on emojis is still evolving — before writing this post, I thought of them as a bit of fun, and a way to add a personal touch in a message to family or friends. I now know that they’re an increasingly important part of all online communication, and they’re not just used in personal messages. In fact, a 2016 study indicated that billions of emojis are tweeted every month and that approximately one in five tweets contains an emoji.[1] Imagine how many emojis are sent on other platforms such as WhatsApp or Facebook.

Some businesses have copped on to this trend and have started using emojis in their digital communications, especially when trying to appeal to younger audiences. A few companies have even published full press releases using just emojis.

But using emojis can be fraught with risks. Companies, and anyone else for that matter, should be conscious of such risks. For a start, emojis look different on different devices. This is an issue for the likes of the Cookie Monster, who frequently uses the cookie emoji. On most devices, the cookie emoji looks like a cookie, but on Samsung devices it looks like a cracker. Emojipedia kindly let the Cookie Monster know about this problem in a tweet. 😱

🍪 Sorry about Samsung, @MeCookieMonster 😢 pic.twitter.com/DcZiF6SyLD

— Emojipedia 📙 (@Emojipedia) July 9, 2017

Emoji users need to be aware of cultural differences too. In most parts of the world, for example, the thumbs up emoji means something nice or cool. Not in the Middle East. Similarly, you won’t make any friends by using the okay emoji in Latin America. Another potential problem is that some emojis no longer represent what they were initially created to represent. The aubergine and peach emojis, for example, are now more commonly used to refer to parts of human body than the actual fruits. One study found that only 7% of tweets containing the peach emoji were related to the fruit. 😲

Some companies have recognised these potential pitfalls and are taking appropriate actions. In fact, things are getting so serious that one company even hired an emoji translator. That’s right — this actually happened. Last year, a chap called Keith Broni, from Ireland 🇮🇪, became the world’s first person to have the job title of emoji translator. He holds a master’s degree in business psychology from University College London and beat off another 499 applicants to land the job. Clearly, he means business. Just look at what he said to CNBC:[2]

“Emojis allow us to imbue digital messages with the non-verbal cues inherent in face-to-face interaction: they allow us to signify the emotional context of a statement which would normally be conveyed in vocal tone, pose or gesture, rather than just the words themselves.”

Wow.

Emojipedia. Twitter accounts. Cookie Monsters. Emoji translators. Using the words imbue and emoji in the same sentence. 😕 I know, I know. Did I mention the emoji spelling bee? Or Emojicon, a three-day convention hosted by EmojiNation? Or World Emoji Day? 📅 You’d be forgiven for thinking that this all sounds like complete nonsense. Perhaps it is. But there are, just maybe, some useful things that economists can learn from the world of emojis. 😜

The 2016 study by Ljubešić and Fišer analysed 17 million tweets from across the globe. 🌎 Using a technique called clustering analysis, they grouped countries into four broad-based clusters based on their emoji usage. The most distinctive emojis in the first cluster, of mainly rich countries, included emojis of weather conditions ☀ and ‘natural occurrences’ like palm trees 🌴 and flowers 🌺 and very few facial expressions. The second group, which included many middle-income countries, was characterised by more expressive emojis 😘 and happy faces 😎. The most distinctive emojis in poorer countries were sad faces 😢, hand symbols ✋ and music 🎶. In other words: people in rich countries are boring, people in middle-income countries are happy and that people in poorer countries sad, but they like music.

The authors also looked at the correlation between emoji usage and a series of World Development Indicators and found the following:

- Negative correlation between life expectancy and “face with tears of joy” 😂 (-0.675)

- Negative correlation between life expectancy and “confused face” 😕 (-0.585)

- Positive correlations between life expectancy and “dog face” 🐶 and “hot beverage” ☕

- Positive correlations between tax rate and “thumbs down sign” 👎 (0.467) and “pouting face” 😡 (0.461)

- Positive correlations between a country’s trade in services (as a share of GDP) and “slot machine” 🎰 (0.626) and “speedboat” 🚤 (0.579)

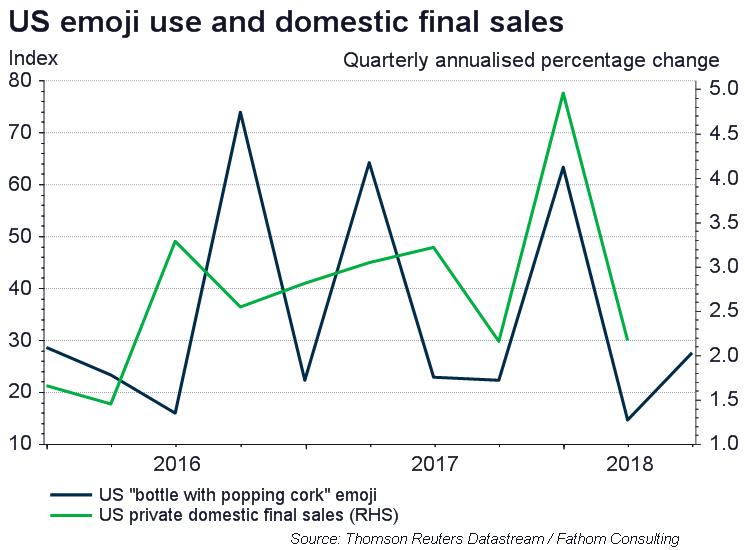

- Positive correlation between GDP per capita and “bottle with popping cork” 🍾 (0.565)

- Negative correlations between GDP per capita and “unamused face” 😒 (-0.428) or “crying face” 😢 (-0.419)

Clearly, cultural differences influence emoji usage between countries, but the economic situation within a country seems to have an effect too, which got me wondering:

Would changes in emoji usage over time within countries reflect changes in the national mood? And could these be used to predict things like changes in GDP?

Hoping to find a trove of data to analyse, I was left slightly disappointed. I was able to find which emojis were most popular across countries, but I was unable to find their use over time. The time series data that I did manage to get hold of was from Google, which shows the frequency of Google searches, by emoji, by country, over time. Nominal data wasn’t available, although it was available on a scale of 0–100 (henceforth called an emoji score), which ranked the number of searches of that emoji across time relative to its peak. I’d have preferred data on emoji use across social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and WhatsApp to emoji searches on Google.

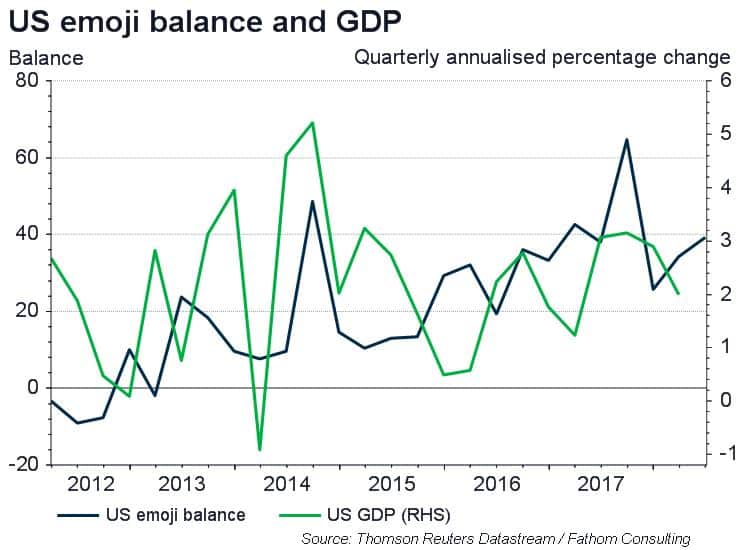

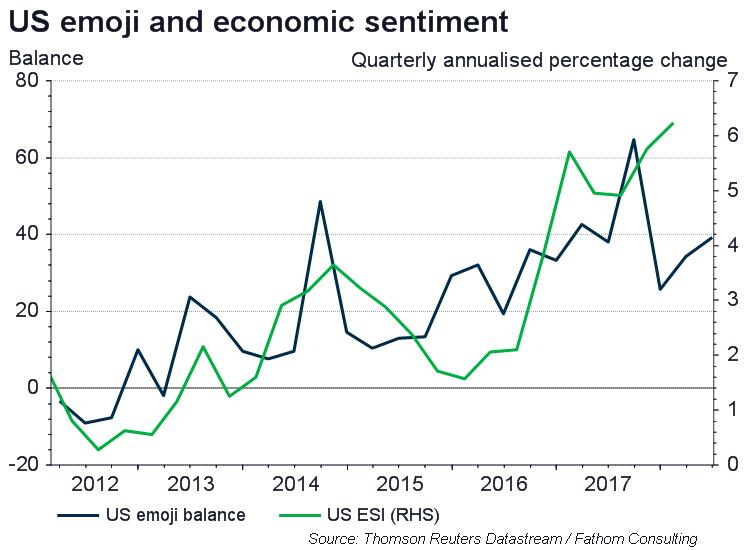

The results were interesting, if not conclusive. I chose the “winking face” 😉 to represent a ‘positive’ emoji and the “angry face” 😠 to represent a ‘negative’ feeling. Subtracting the ‘sad’ emoji score from the ‘happy’ emoji score gives an ‘emoji balance’. I found a weak, positive correlation (0.20) between the US emoji balance and US GDP growth, although there was almost no correlation between the US emoji balance and US payroll growth. There was a strong correlation (0.66) between the US emoji balance and US economic sentiment (reflected by our ESI). There was a very weak, positive, relationship between US usage of the “bottle with a popping cork” 🍾 cork emoji and US GDP and our US ESI. But there was a more noticeable positive correlation between this emoji and the change in US payrolls (0.36) and US growth in private domestic final sales (0.43). The data for the UK didn’t appear to exhibit any clear relationship.

The findings in the US might suggest that changes in emoji usage over time might be useful to predict some economic indicators. There are, of course, limitations to this analysis (including the small sample size and uncertainty about whether Google searches accurately reflect emoji usage on other platforms, etc) and it would be premature to draw any definitive conclusions.

But for those willing to pay, data from the biggest social media platforms could yield more conclusive results. Who knows – such information may well become freely available to the public in the future. The advantage of looking at such data is that they’d potentially be instantly available, which could make them very handy predictors of more traditional economic data releases (like GDP growth or employment growth), that move financial markets. Savvy investors may want to inquire about the availability of such information or keep an eye open for their release. This blog post may not have provided the definitive answer about the usefulness of such information, but at least I can say one thing with more certainty — telling someone that you hate emojis isn’t the best pre-date chat.

Thanks for reading 😘 😘

[1] Nikola Ljubešć and Darja Fišer, ‘A global analysis of emoji usage’, Proceedings of the 10th Web as Corpus Workshop (WAC-X) and the EmpiriST Shared Task, Berlin 2016, pp. 82–89. Available at: http://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W16-2610.

[2] https://www.cnbc.com/2017/07/17/meet-a-guy-who-makes-a-living-translating-emojis.html