A sideways look at economics

Summer’s drawing to a close, and there’s huge uncertainty about what is to come. Will a vaccine be approved this year? Will the coronavirus return with a devastating second wave? Will Lionel Messi really leave Barcelona on a free transfer? (Yes, no, maybe so are my unscientific opinions.) One of the stranger aspects of this summer has been the UK government’s approach to indoor dining. Many countries have banned it, out of concern that it’s a ripe breeding ground for the infectious disease that has wreaked havoc on the world. Others have allowed it, sometimes with new rules to keep customers safe. The UK government, by contrast, is probably the only one subsidising it, paying half the cost of food and non-alcoholic drinks at sit-in restaurants (up to £10) Monday through Wednesday in August.

Back in July, when the UK chancellor, Rishi Sunak, announced the Eat Out to Help Out (EOTHO) scheme, it was met with a mixture of bemusement and ridicule. Subsidising restaurants? Another handout to the privileged few, people said. A common view on Twitter was that it wouldn’t work: restaurants were empty, not because the price of starters was too high, but because people were scared of catching or spreading the virus. Others were amused by a government trying to tackle obesity, a risk factor that increases mortality from coronavirus by 48%, while at the same time offering half-price Big Macs. Economists pointed out that eating at restaurants has negative externalities (further spread of coronavirus), and subsidies were the precisely the wrong policy.

Let’s take each in turn.

First, inequality. It takes money to reap the rewards from EOTHO as you need to spend £10 of your own to receive the maximum £10 subsidy. Eating out is a luxury for many and so the scheme seems likely to disproportionately benefit repeat users with resources to spare. With unemployment spiking, and the budget deficit soaring, I can see why some would find it a little weird that HM Treasury should pick up part of the tab. There’s one type of inequality it may be helping at the margin: intergenerational. On the first EOTHO night, I saw a winding line of teenagers outside my local Nando’s. Some younger members of Fathom’s staff were reportedly keen on getting some PERi-PERi too.

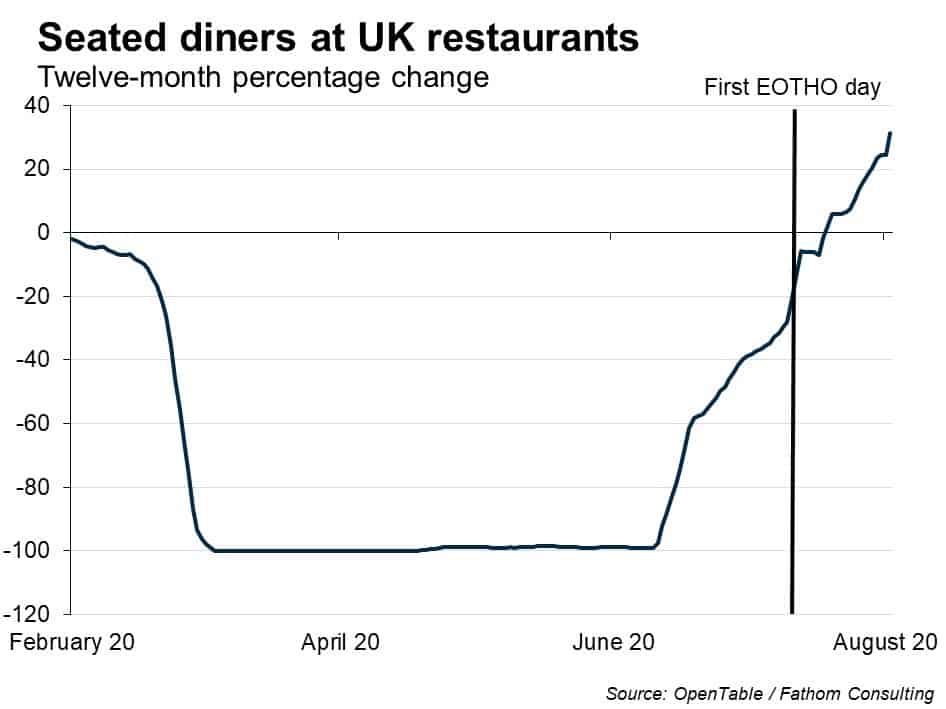

Second, fear. The public probably was initially afraid of eating indoors. In July, the hospitality sector had just re-opened, and a slim majority of Brits thought the easing of restrictions was going too fast. Restaurants were open but not many people were going: takings were down by two-thirds. However, incentives matter. A £10 subsidy seems to have been enough to change the calculus on whether to eat out or not for many. Restaurant trips, which admittedly had been increasing through July, have been turbocharged in August. Visits peak on EOTHO days, but activity has continued to rise through the week, suggesting a legitimate increase, not dislocation of demand. With psychological scarring a looming threat to full economic recovery, it’s easy to see how nudge unit types might see the broader benefits of such a policy.

Third, obesity. There’s not much to say here. Obesity has clear negative externalities on the health system, as coronavirus has exposed, and unhealthy diets play a big role. It’s therefore hard to justify McDonald’s getting a government subsidy. If anything, it should be more heavily taxed. And I say this as someone who loves McDonald’s. In fact, I’m eating a chicken nugget right now.

Fourth, externalities. This maybe the most controversial and ultimately will decide whether encouraging the public to overcome their fear of the virus will eventually be seen as a good or bad thing. In many countries, indoor dining has been found to be a vector that spreads coronavirus. It’s also true that the UK infection rate has increased in August, reaching a post-lockdown peak of 1522 new cases yesterday. However, the rise started in July, ahead of EOTHO, and has decelerated for most of the month. Moreover, the jump in cases has been much less severe than has been seen in France or Spain, where eating out is not being actively supported by government.

Taking it all together, then, EOTHO has probably: made rich Brits fatter and less fearful, while helping to boost economic activity in an ailing sector without sparking a resurgence in coronavirus cases (for now). Was it worth it? I don’t know. It’s hard to think clearly after your twelfth chicken nugget. One thing I do know is that Lionel Messi would fit like a glove on Man Utd’s right wing.