A sideways look at economics

It is exactly a year since we were handed the keys to our first house, and my main memory of the last twelve months is the do-it-yourself spree that ensued. I must confess that I was never much of a DIY type, and sometimes I miss the days of renting when worrying about something that needed fixing ended with a quick phone call to the landlord. But last June I mortgaged my life for a heap of bricks and mortar, and promptly began to DIY the heck out of it: painting, drilling, fitting, fixing, cleaning – even drinking builders’ tea between jobs, which is a new departure for a Greek. Maybe it was the guiding influence of my brother-in-law who is as hardcore a fan of DIY as he is of Iron Maiden. Or maybe the fact that after 14 years in the UK I have acquired the quintessentially British obsession with DIY is an indicator that I am finally becoming ‘Britainised’.

Tea-drinking and DIY are elements of British heritage which in my eyes seem inextricably bound together in the process of ‘nestbuilding’. Various generations of British people I am acquainted with seem to have indeed painted their own ceilings, hung their own wallpaper or built their own garden shed and have been fuelled during their amateur endeavours by tea. In that sense, they have reflected the image of their professional counterparts, the bricklayers and plasterers who constitute the ‘British Builder’ — a figure both reviled and revered but seemingly always thought of doing everything while enjoying a cuppa. The dominance of tea-drinking in British society should be relatively clear to the average reader of this blog given its past coverage. The DIY obsession is a bit more sublimated perhaps — at least it was to me — and here I am attempting to put it into perspective.

To witness how fondly DIY is seen by British people one has to just watch TV. In a world of ever-evolving entertainment options, one genre that has managed to capture the attention of viewers across the UK is property television. From nail-biting high-end estate agency dramas to heartwarming DIY shows, the British thirst for property programmes seems to be unquenchable. It doesn’t matter that you have no intention of buying and/or renovating a house or tackling some major DIY, the allure of property programmes is unparalleled. These shows offer viewers a glimpse into aspirational living, allowing them to momentarily transcend their everyday lives and imagine themselves in different, perhaps more lavish, surroundings.

Accordingly, ads showcasing DIY products strategically flood the TV around the time of the March spring clean. During that season the planetary influences line up to draw British consumers into those temples of the DIY movement – the Screwfixes, B&Qs, Wickes and B&Ms, where new, wannabe ‘British builders’ agonise over the right shade of light blue emulsion, and load their trolleys with rollers, dustsheets and shelving brackets. The spring wave of British DIY consumers is so certain —more certain than the arrival of spring or indeed summer weather — that equity investors are banking on it.

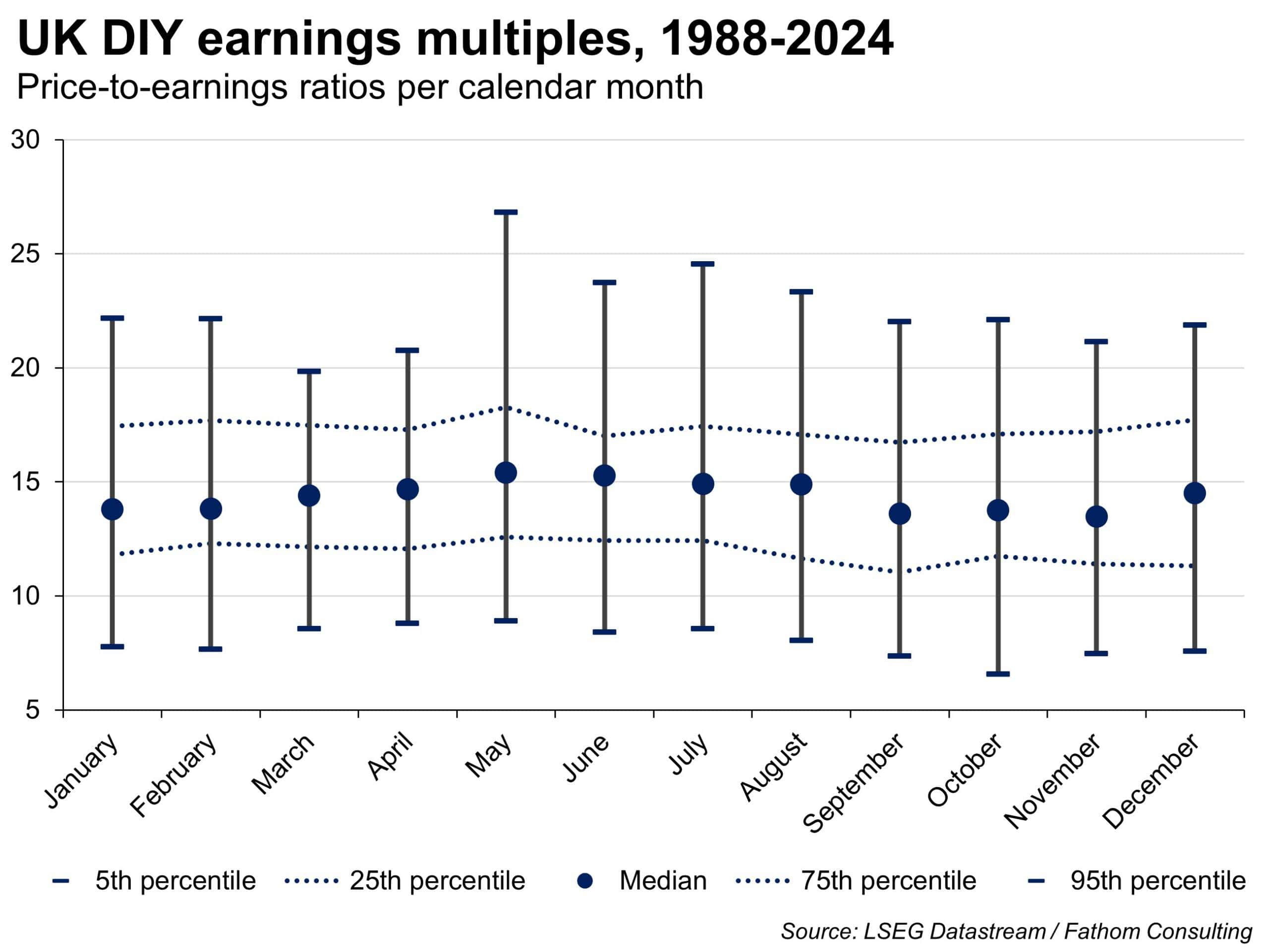

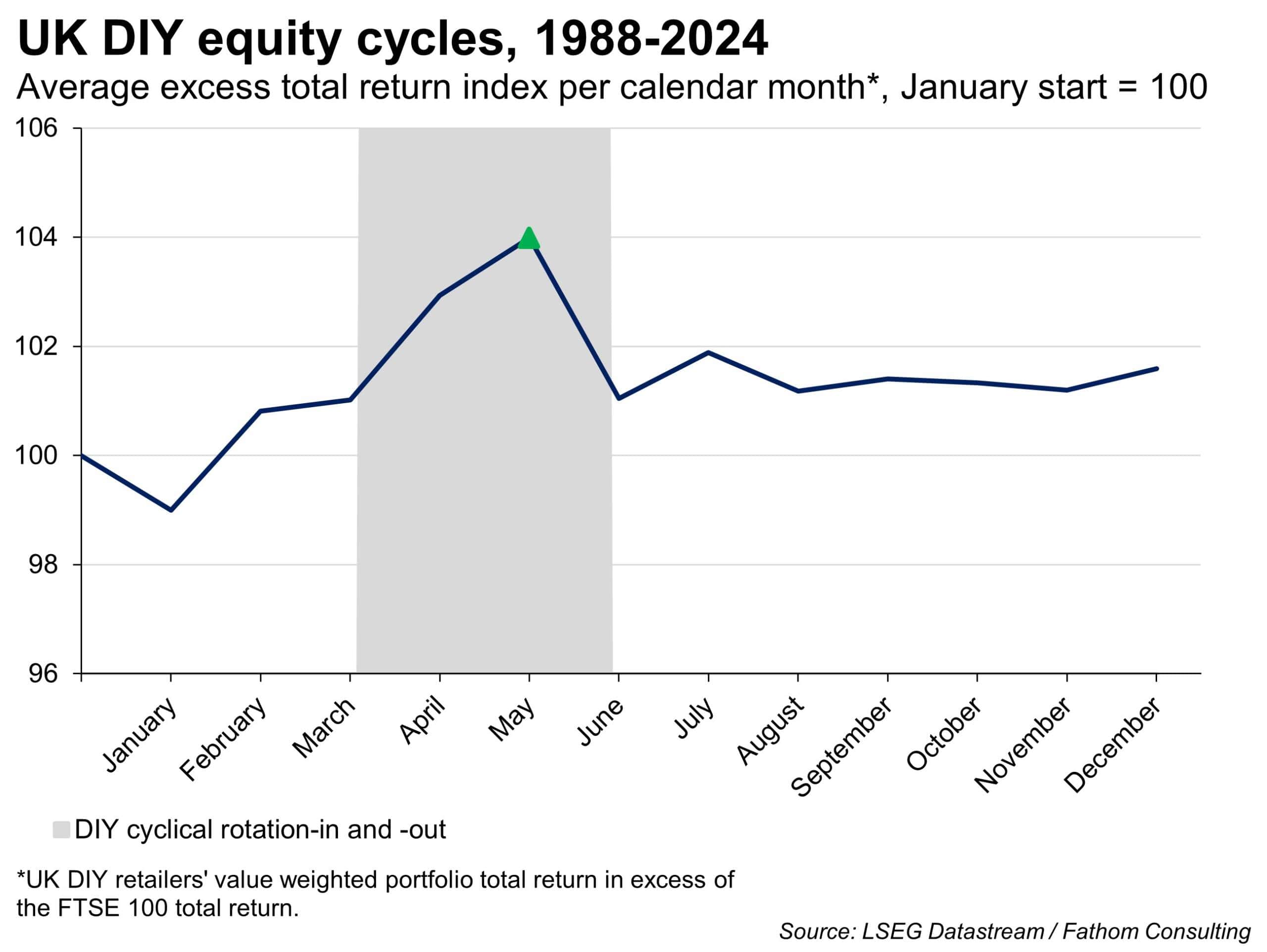

Briefly removing my DIY beanie hat and setting down the mug of tea to return to the day job, I can confirm that the equity returns of the UK’s DIY retailers exhibit strong seasonality between March and July. Equity investors start to buy shares in DIY retailers in March, in anticipation of the revenue spike related to the waves of UK consumers flooding through their doors. Half of that time between 1988 and 2024 equity investors were willing to pay slightly more than 15 times the earnings of the DIY retailers to reap the benefits of the spring growth in DIY sales. Interestingly, 5% of that time investors were willing to pay as much as high as 26 times the earnings of the DIY companies, with these occasions being the two years after the start of the pandemic in 2020. The lockdowns clearly encouraged British homeowners to even greater feats of DIY…

The DIY tsunami usually starts to dwindle once the summer holiday season begins, by which point most equity investors have rotated out of DIY shares, prompting the shrinkage of the valuations range post-May, as shown above. During those months, investors would have enjoyed up to around 4% higher average year-to-May return and 3% March-to-May return than if they had bought FTSE 100 — the index of the 100 largest companies listed in London. Those are not negligible takings for such a simplistic, seasonal trading phenomenon.

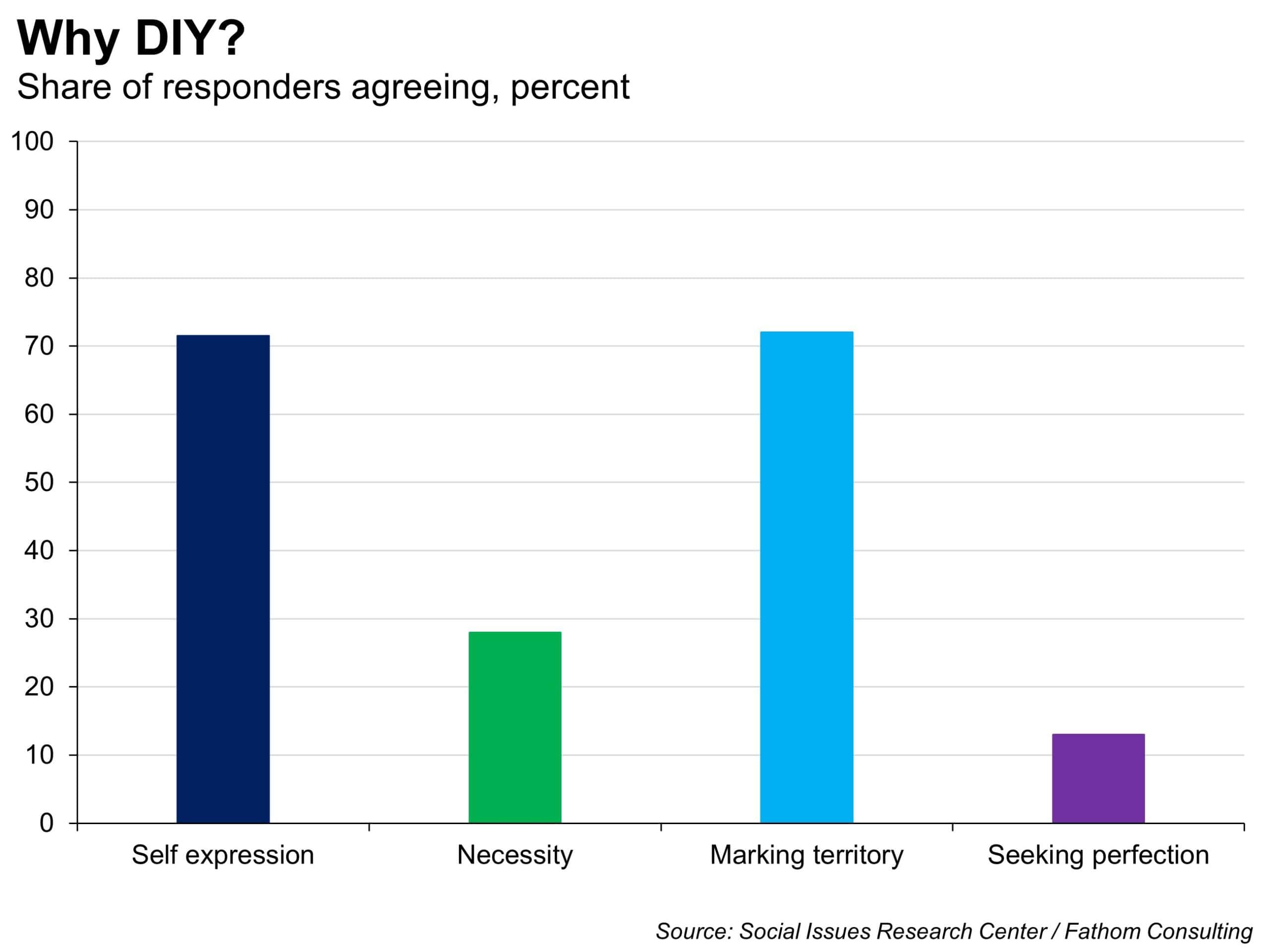

Why do British people engage in DIY to such an extent that their actions create predictable and tradeable socioeconomic patterns? According to a survey conducting by the Social Issues Research Centre the reasons are numerous and complex, as well as not mutually exclusive. Many see DIY as a rare opportunity for creativity and self-expression — 72% of responders agree with that DIY function. For 28% of responders DIY constitutes an unwelcome necessity, driven mainly by economic considerations. There is also a group of people who believe that a building structure can never feel like ‘home’ unless it has been modified enough to reflect that they moved in (72% agree that DIY is a form of claiming your territory). Then there is a final group who believe that if you want a job done well, you must do it yourself (8% see DIY like that).

Thinking about it under these banners, I would classify myself as someone who was sucked into DIY due to necessity,[1] and stuck with it because I and my brother-in-law the DIY champion have — happy to report — a (so far) well-founded belief that if a job is done by us then it is usually done better. In any case, I can proudly report that as of last year I have become a bit of a DIY-er, who is happy to save money and time, while achieving ‘a job well done’ through planning and moments of pause and reflection – with a cup of tea near to hand.

Before /after

[1] My 2023 DIY initiation happened due to time constraints rather than economic constraints. As I was a ‘late bloomer’ important life milestones, such as moving to your house and having a kid that usually happen in the course of years or at least months occurred over the course of one month only for me, as outlined in a previous blog.