A sideways look at economics

There is a contagion spreading around London, infecting commuters from all walks of life. These gyrating duplet organisms vary in size, shape and colour and are replicating in variants of greater and greater wattage. Once contaminated, a symbiotic relationship is formed… I am speaking of course about bicycles.

Transport for London (TfL)[1] estimates that 1.26 million two-wheeled trips were made every day in the capital in 2023, a 20% increase from 2019 and equivalent to a third of all Tube journeys. While this may seem substantial, London still lags behind more cycle-friendly European capitals. In Copenhagen cycling represents 49% of daily trips, according to data from the European Cyclists Federation, compared to a mere 5% in London. The government hopes that walking or cycling will make up 50% of all journeys in UK towns and cities by 2030, to help meet net-zero targets. In London, mayor Sadiq Khan aims for 80% of journeys to be made by walking, cycling and public transport by 2041.

To encourage this growth in London, war has been declared on four-wheelers, with ever-expanding cycle lanes, the introduction of low and ultra-low emission zones (LEZ or ULEZ) and speed limits being cut to what could be considered a bit slow even by a rural village’s standards.[2] TfL estimates that 22% of Londoners live less than half a kilometre (400m) away from a high-quality cycle path. By the end of 2020, 4% of all Londoners — about 300,000 people — were living in areas covered by the new 72 Low Traffic Neighbourhoods.[3] Former Mayor of London Boris Johnson’s hope in 2010 that “bikes would become as common as black cabs and red buses in the capital” are certainly ringing true.

There’s a plethora of good reasons why TfL should continue developing safe cycle routes across London. Cycling is obviously one of the greenest ways of commuting, after a run or walk. Public transport is the next best option, so how do the two compare? Commuters taking the underground each contribute an average of 0.3645 kilograms of carbon dioxide (kgCO2e) per journey.[4] Commuting by Tube twice a day for four days a week every working week of the year produces 135.30 kg CO2e

equivalent to just under half the carbon footprint of a holidaymaker’s one way trip to Rome.[5] Furthermore, even if one’s own conscience might be cleansed when avoiding the Tube, a substantial number of people would need to switch to cycling before London Underground emissions declined significantly. Clearly the Tube is not as environmentally unfriendly as it may seem compared to cycling.

So what about the cost benefits of cycling?. Taking the average Underground fare to be £4.44 per trip,[6] the same Tube commuting racks up £1,648.13 every year… roughly the cost of eating out out twice a month and consuming an average of 2.47 pints per week in London[7] — or just consuming 4.7 pints a week, if you skip dinner (this TFiF doesn’t discriminate). Furthermore, Cycling UK estimates the average yearly cost of buying and maintaining a bike to be £976.[8] When referenced against doing practically anything else in London, the Tube is reasonably priced.

So if the environmental and cost benefits of cycling aren’t substantial, what is? A study from The University of Edinburgh[9] from 2024 analysing 378,253 people suggests “people who cycle to work are less likely to be prescribed drugs to treat anxiety or depression than those who commute using different modes of transport”. The working Glaswegians and Edinburghers (or Edinburger, Dunediner or Edinbourgeois, depending on who you ask)[10] included in the study lived within around a mile of a cycle path and had no prescriptions for mental ill-health at the start of the study. To avoid potential bias from a generalised linear model (e.g., healthier people decide to cycle more), the researchers adopted an instrumental variable (IV) approach, using the straight line distance from an individual’s residence to the nearest cycle path as their IV. Researchers discovered a 15% reduction in prescriptions for anxiety or depression in cycle commuters in the five years after 2011 compared with non-cyclists, thus suggesting that commuting by bike decreases the risk of mental ill-health. Since the research analyses Scots, one could argue that replicating the study on Londoners could garner slightly different results. However, the positive mental and physical wellbeing effects of regular exercise cannot be understated.

So the question looms; if I live close enough to my office, should I be cycling to work and, further still, encouraging all my friends to do so? The idea of an 8:00am peloton stress-induced cycle into the office, paired with a >50% chance of rain, brings feelings of both appeal and repulsion. While my commute would be reduced by a staggering 10 minutes, 364.5g of carbon dioxide and £4.44 compared to the tube, navigating hoards of Lycra-cladded road bikers, rule-bending moped riders and frustrated motorists makes the savings seem less enticing.

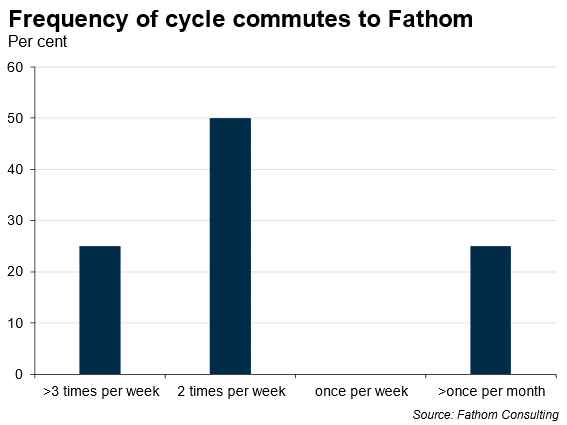

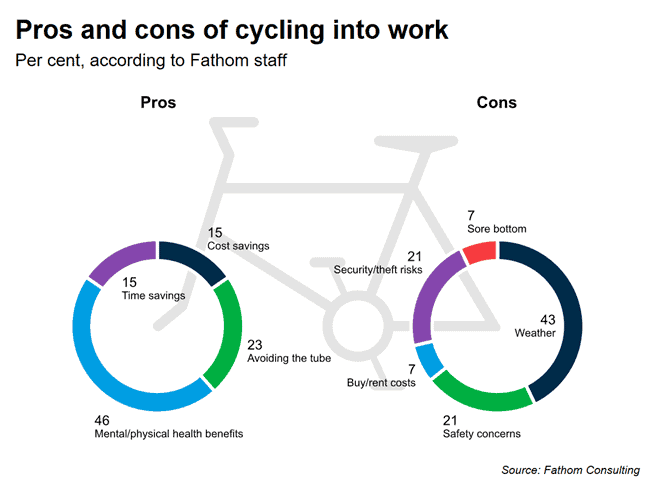

And quizzing both Fathom cyclists and anti-cyclists alike, it’s clear I’m not the only one struggling with the decision. Only four Fathomites had ever cycled into the Fathom office. One cycles into work more than three times a week. Two are on two wheels twice a week, and the final Fathom cyclist only avoids the Tube once or twice a month. It must be noted that since COVID, Fathom has run a hybrid approach to working, with around 50–60% of working hours spent at the office. Of the past and former cyclists, I queried them on the best and worst parts of their cycle commute. Perhaps unsurprisingly considering the analysis above, environmental impact and cost savings ranked last and equal second last (along with time savings) as a reason to cycle, with 0% and 15.4% respectively of the total vote when asked to select the two standout features of biking into work. Unsurprisingly, the main appeal of cycling to work was the mental and physical health benefits, taking 46.15% of the votes.

Turning towards the negatives, it appeared that the lower cycling rates seen in London compared to other European cities aren’t completely down to poor cycling infrastructure. 42.9% of votes cited the weather when Fathom cyclists were asked to provide the worst things about cycling into work. The costs of buying or renting a bike, and a sore rear end, were the least common negatives, each with 7.14% of the total votes. Unfortunately, of the 21 respondents that have never commuted to Fathom avec deux roues, only two plan to eventually cycle to the office in the future.

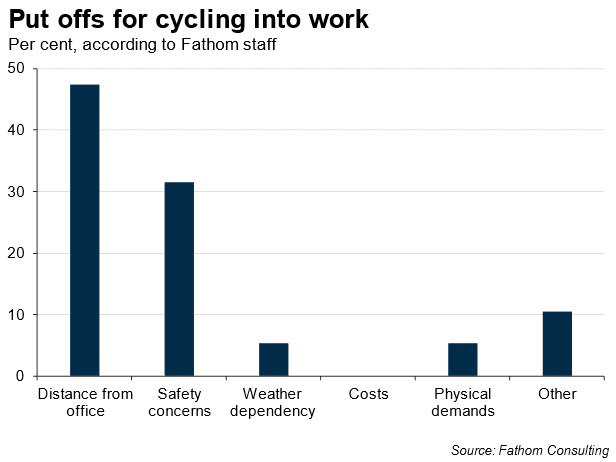

To the 19 that don’t plan to, I posed a simple question; why not?[11]

As explored in a 2018 TFIF on commuting distances,[12] distance from the office accounted for nearly half of the votes for not cycling to the office – which is unsurprising, considering one third of Fathomites don’t even live in London. For the people who cycle, weather is a bigger negative than safety concerns; whereas for the non-cyclists the opposite is true. Maybe more should be done to reassure non-cyclists that it is safe to give two wheels a try.

So, should we dust off the helmet, slip into the clip ins, high-vis up and blast the bike to 110 RPM, come hell or high water, every commute? The answer is, if you live within a reasonable distance from the office and can cycle safely and competently, why not?[13] But just know that riding the occasional Tube here and there won’t break the bank or the planet.

[1] London’s Cycleway network will have quadrupled since 2016 as a major new Cycleway opens in Southwark – Transport for London (tfl.gov.uk) New TfL data shows sustained increases in walking and cycling in the capital – Transport for London

[2] In 2020, TfL changed all the speed limits on its roads in central London from 30mph to 20mph

[3] LTNs, which TfL claims “helps to make streets around London easier to walk and cycle on by stopping cars vans and other vehicles using quiet roads as shortcuts”.

[4] Figure taken from TfL figure of 40.5g CO2e per km multiplied by 9km, the average length of trip on London Underground. Total number of working weeks = 52 – 5.6 = 46.4 https://tfl.gov.uk/corporate/transparency/freedom-of-information/foi-request-detail?referenceId=FOI-1827-2223

[5] Curb6 estimates the carbon dioxide emissions budget for one person travelling from London Heathrow to Leonardo da Vinci–Fiumicino as 286.0kgCO2e

[6] London tube fares 2024, ticket prices updated (londontubemap.org) The average tube fare was calculated taking the average of a trip between zone 1 to 2, zone 1 to 3, zone1 to 4, zone 1 to 5 and zone 1 to 6.

[7] The average price of a pint in the UK and around the world (finder.com) + taking a meal out to be £30 per person = £60 per 4 weeks = 780 per year. (Across 2 weeks, I would estimate the same to be spent on eating out more frequently at cheaper establishments). Pints calc: (1648.13 – 780)/(6.75*52).

[8] How much money can you save by cycling? | Cycling UK

[9] Cycling to work linked with better mental health | The University of Edinburgh

[10] What are natives of Edinburgh called? People from Glasgow are Glaswegians, and from Paisley are Buddies, but no-one I have met know what those from Edinburgh are called. | Notes and Queries | guardian.co.uk (theguardian.com)

[11] Each person was asked to give one vote. Other consists of “Disproportionate number of angry cyclists wearing Lycra” (one vote), and “Unwillingness to ‘faff around with a shower once I get in’ ” (one vote).

[12] An Italian perspective on the British commuter – Fathom Consulting (fathom-consulting.com)

[13] Just a helmet and a leisurely pace will work too.