A sideways look at economics

The Milles Collines is a beautiful hotel in Kigali, perched atop one of the hills that gives Rwanda its nickname: the land of one thousand hills. The back terrace looks out onto a tropical garden dotted with bougainvillea. Today, it is an oasis of calm in a peaceful city, but it was made famous as an oasis from unimaginable violence when 1000 people sheltered there during the country’s 1994 genocide. During my recent sabbatical, in the tranquil setting among chirping birds, I was left to ponder criticism about its long-serving president: Paul Kagame. Freedom House, for example, classifies the country as ‘Not Free’ with a Global Freedom Score of 21. But the country’s economy has performed well. Is there a dichotomy between political freedom and economic progress?

Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, is neat and orderly. Each month, residents take part in a compulsory community clean-up, a practice described as ‘mandatory volunteering’. The country was one of the first in the world to ban plastic bags and airport authorities will confiscate any they find you with. Tree-lined streets buzz with the soft hum of motorbikes whose drivers carry spare helmets for their passengers. Traffic is light, but it is dealt with calmly; a stark contrast to the constant honking I recently encountered in Addis Ababa. By all accounts, the city is safe, with law enforcement visible throughout. Local residents assured me that corruption was so rare as to not enter conversation.

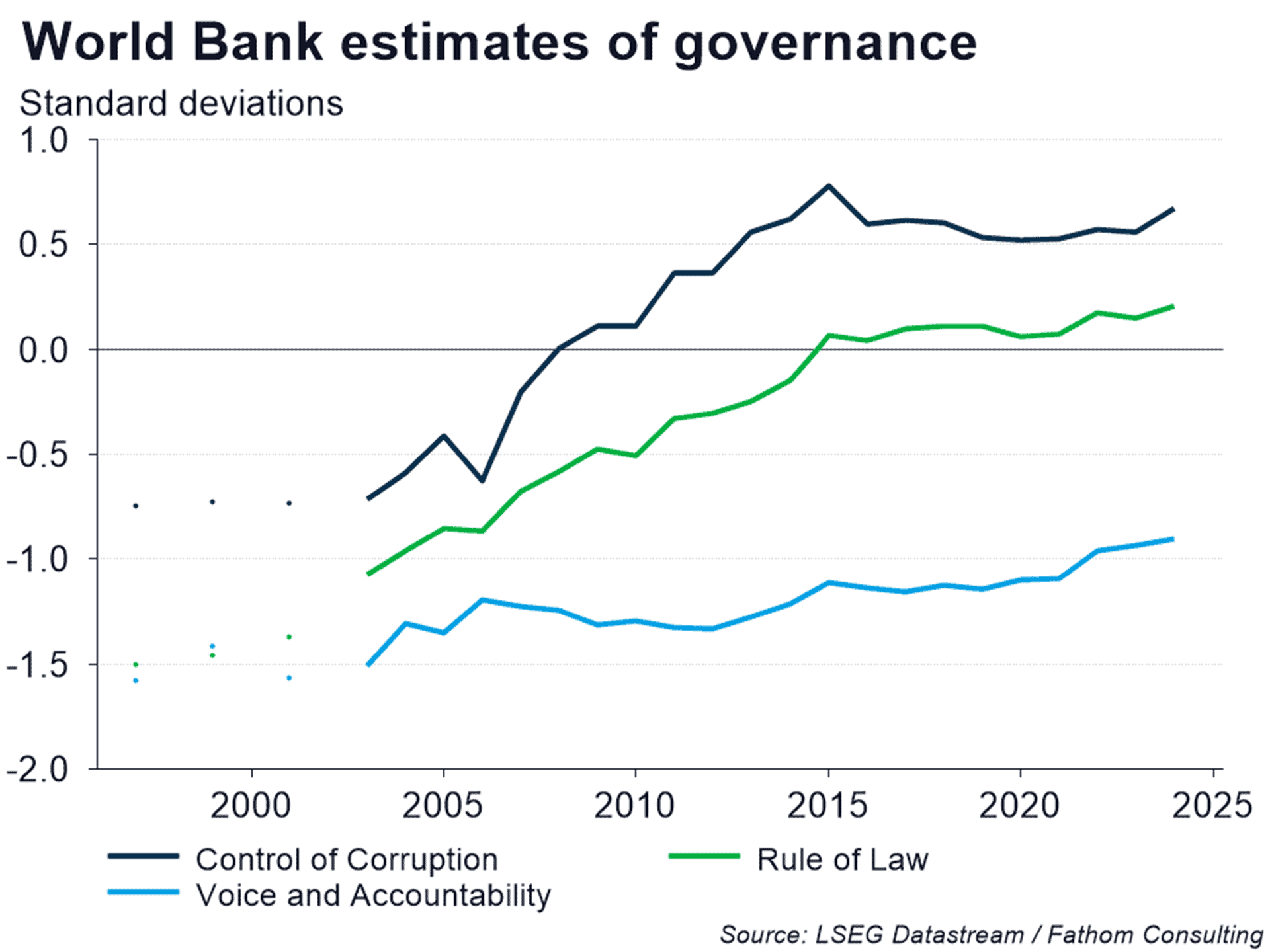

These intangible experiences are reflected in Rwanda’s improving Fathom Political Index score, observed during Mr Kagame’s reign. The Voice & Accountability metric remains floundering in negative territory, implying a democratic deficit. However, the country has made notable progress on the Control of Corruption and Rule of Law sub-indicators. We have previously pointed out that the list of high-income countries is filled exclusively with democracies, commodity exporters and city states. In fact, being democratic is close to a pre-requisite for achieving high-income status, or, at least, being rich strongly correlates with adopting democracy. There is no such clear link among poorer countries.

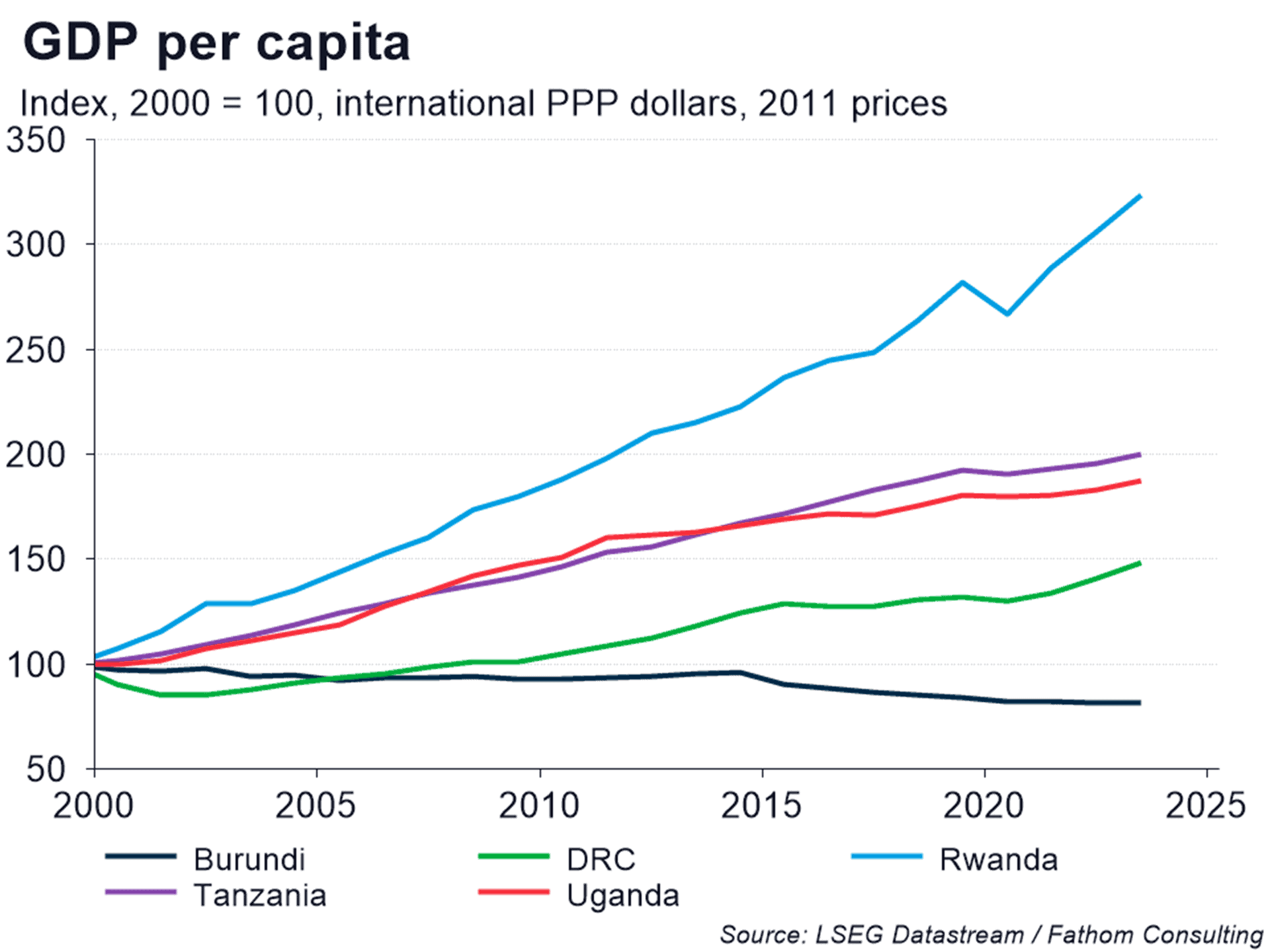

Domestic stability and a well-functioning government are not societal cornerstones, they also help with economic growth. China is perhaps the most famous example of a country that has grown rapidly without democracy or even democratisation. Rwanda appears to be modelling itself on a Chinese-style form of governance, with a large role for public investment and a desire to replace imports with domestic production. Since 2000, when Mr Kagame came to power, this model has achieved success. The country has outperformed its regional peers economically, achieving a much faster increase in living standards than any of its neighbours. Rwanda is now second in GDP per capita (PPPs) among countries it shares a border with.

The human capacity to go through hell and keep going is astounding. From an outsider’s perspective, Rwanda’s society, after its horrific trauma, appears to have rebuilt the country tremendously well. Many in the country credit this to the person who has been ruling for most of that time. The bartender at Milles Collines joked that he was disappointed with the most recent election result, where Mr Kagame received 99% of the vote. He felt the president deserved 100%. I am writing this from the UK, a peaceful and prosperous democracy. It would be wrong to declare that other people ought to sacrifice political freedom for stability and economic growth. However, I was somewhat reassured when the bartender later went on to complain about the price of rent. I guess in countries around the world, Democratic or not, rich and poor young adults can all agree that rent is too damn high.

Rwanda’s national mourning period begins with Kwibuka (Remembrance), the national commemoration, on 7 April and concludes with Liberation Day on 4 July.

More by this author