A sideways look at economics

The weather was great when I was last home and we enjoyed a couple of lovely family barbecues. You won’t know this, of course, but my dad considers himself quite the expert at the barbecue — as all dads do! That’s why he’s incredibly fussy about allowing his steaks a decent amount of time to marinade. Anything short of four hours and he’ll complain that the taste will be ruined. On the other hand, if my brother is in charge, the notion of marinading won’t even enter his head. What’s all this got to do with economics, you ask? Simple. It’s all about planning well in advance, concentrating not merely on the here and now but on the long-term result — employing what’s called cathedral thinking.

On the day this blog is published I will be on annual leave, in Milan, the home to the Duomo di Milano. This stunning cathedral took nearly six centuries to complete, with construction beginning in the Middle Ages, in 1386, and finally ending in 1965. From the first architect to draw up the plans to the artisan who laid the first stone, workers knew they wouldn’t live to see the completed masterpiece. But they proceeded anyway, knowing that the future cathedral would be enjoyed by many generations to come. This is what cathedral thinking is all about — a commitment to the long-term implementation of a major plan.

It prompts us to view problems such as climate change as a cathedral in the making — a monumental challenge that requires collective effort, perseverance and investment. It urges governments to implement policies that prioritise sustainability, renewable energy and environmental conservation, even if the benefits may not be fully realised during the tenure of current leaders. By adopting this mindset, we can construct a better future for generations to come.

At times, though, it can feel like there isn’t a place for long-term thinking in today’s fast-paced world. In his TED talk, ‘Cathedral thinking is dead. Long live cathedral thinking’, Jonathan Thompson suggests three reasons why planning for the future is less common today.

First, he points out that in the Middle Ages there was little progress of any sort. Living standards were fairly constant until the Industrial Revolution in 1750, and therefore it was easy to predict what life would look like for the next generation, or the one after that. Existing in such a stagnant point of history, Thompson argues, meant that your time horizon was pretty long. Contrast this with today’s economic landscape, characterised by rapid technological advances, where it’s very difficult to predict the future. As a result, our time horizons have become shorter and we focus on the near-term.

Second is the curse of the clock. In the Middle Ages, days were marked by the rising and setting of the sun. Fast forward to today, where the majority of us have a smartphone in our pocket (or, if you’re my dad, a watch on your wrist): we’ve become so consumed by hours, minutes and seconds, rushing from place to place, that we’ve lost our ability to truly feel time in its fullness, to contemplate life years and decades ahead. The contrast between the steak my brother serves up and Dad’s marinaded offering shows how even slightly differing attitudes to time can have a very different end result — in the form of a tastier meal!

Third is the decline of the divine. Religious worship played a huge role in the Middle Ages and was a key motive in the building of magnificent cathedrals as a way of glorifying God. In many faiths, the promise of an afterlife expanded people’s time horizons to think beyond their life on earth. Today, however, far fewer people are religious. Indeed, in the 2021 census, 37.2% of people in England and Wales said they had “no religion”, up from 25% in 2011. Without a belief in the afterlife, people’s focus shifts to success in this life and therefore their time horizons shrink.

I recently listened to an episode of the Hidden Brain podcast featuring Laura Carstensen, a professor of psychology at Stanford University and founding director of the Stanford Center on Longevity. In the podcast, she discussed her research on the science of ageing, most notably her finding that older people are happier. This finding, known as the ‘paradox of ageing’, seemingly goes against a lot of what modern society tells us about growing older, i.e., that our young, carefree years are the happiest of our life. Carstensen, as well as my colleague Andrea in a previous Fathom blog, wondered why the opposite appeared to be true.

After considering a multitude of possible reasons, Carstensen finally concluded that it all boils down to time horizons. As people age, their time horizons grow shorter, and they see their priorities more clearly. Up until this point, researchers had typically used age as the contributing factor for observed differences between the young and the old. Unsurprisingly, the amount of time a person perceives as having left in their life is highly correlated with their age. But Carstensen found that it’s the number of years a person perceives as having left, not the number of years since they were born, that is the most important factor influencing people’s goals and motivation. By imposing time constraints, and thereby altering people’s time horizon, studies have found that preferences change in both younger and older people.

This interesting finding — that people’s motivation and goals change with time horizons — got me wondering whether time horizons may also be affecting the decision-making of those in government.

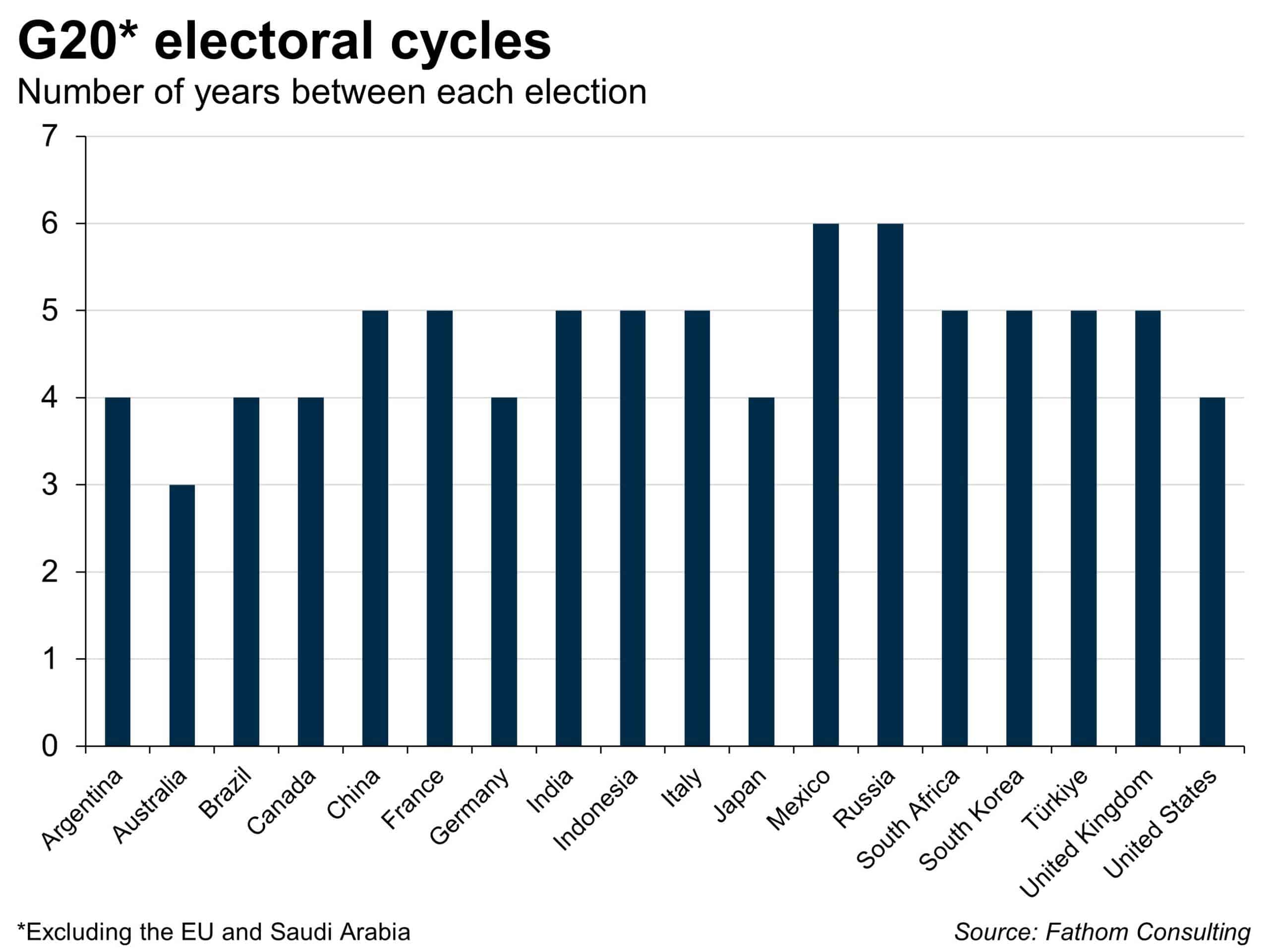

For many politicians and world leaders, decisions are often influenced by the short-term nature of political cycles. The chart below shows the length of an electoral cycle in each of the G20 countries, with an average of 4.7 years. Politicians often face pressure to deliver quick results and show progress within the limited time they have in office. Unfortunately, this can sometimes lead to policies that prioritise short-term gain over long-term prosperity. After all, it’s easier to focus on quick wins that will appeal to voters in the short run and increase chances of re-election, rather than tackling complex issues that may only bear fruit years down the line.

However, such short-term thinking may make little if any progress in addressing the most significant challenges of our time. Let’s take climate change again as an example. This is not a new phenomenon. The term ‘global warming’ first entered the public domain back in 1985 when US scientist Wallace Broecker used it in the title of a scientific paper. By 1988, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was formed to collate and assess evidence on climate change, and by 1995, in its second report, the IPCC concluded that the balance of evidence suggested a “discernible human influence on the Earth’s climate”. So, policymakers have known about this problem for almost three decades, and yet progress has been markedly slow.

Climate change is not the only significant long-term challenge facing governments, of course. Among other things, political leaders must also plan to deal with the effects of an ageing population, the threat of artificial intelligence, and rising tensions between China and the West, to name but a few. So, how can those in power extend their time horizons beyond the current political cycle and plan sufficiently for the future? Maybe they should look at cathedral thinking.

In Wales, it seems like they’re doing just that. In 2015 the Welsh parliament passed the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act to extend politicians’ horizons beyond the next election or budget cycle and govern with future generations in mind. A Future Generations Commission was created to “ensure decisions taken today meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Now, all Welsh public policy and spending must go through the commission to be assessed on a number of well-being goals to make Wales “healthier, more resilient, equal, cohesive, prosperous, globally responsive and culturally vibrant”.

One of the commission’s early forays was to challenge the government’s entire transportation strategy, which at the time focused investment on roads rather than public transport, by asking how they were assessing the carbon impact of their spend. As a sign of the impact the commission’s efforts are having, in February 2023 the Welsh government announced the cancellation of most major road-building projects, using the money saved to improve existing roads and invest in sustainable transport infrastructure instead.

What is the broader significance of this example of modern cathedral thinking? It certainly shows that, given a change in the perceived time horizon, adaptive thinking is possible at government level. It will, however, continue to be an uphill struggle to persuade those in power — both locally and globally — to stop procrastinating and to work cohesively towards a sustainable future, one that transcends political cycles and prioritises the well-being of generations to come. Just like the builders of grand cathedrals, our actions today can have the power to shape a brighter tomorrow. Ciao!

Duomo di Milano | Picture by my friend, Olivia Shaul

More by this author