A sideways look at economics

Was Paul Volcker the greatest Fed chairman, the GOAT of the Fed? He put the inflation genie back in its bottle. Or was it Ben Bernanke, who hauled the economy out of the GFC? Or Alan Greenspan? He oversaw the longest period of sustained growth and low inflation. Perhaps it was Janet Yellen: she navigated the economy back to stability after the turmoil of the GFC and its aftermath. Or maybe it’s Jay Powell? It looks like he’s going to achieve an immaculate disinflation.

The pronouncements of these great people are parsed and dissected endlessly. Fortunes are made and lost with good and bad calls about what they will do next. If only we could see into their minds, we would be able to see… what? The chain of reasoning and other motivations upon which so much hinges – our standard of living; whether we have a job; whether our children will do better than us. The economic world turns on their whims.

Hold on, though. Is this really a good characterisation of how the world works? That a handful of great people make choices, while the rest of us wait with bated breath to see what those choices will mean for us? I don’t believe it is. The most those great people really did was nudge the dial a fraction – important nudges, but nudges nevertheless. That’s the most any of us can achieve in a macro sense. Macro trends are the sum of billions of choices, over which even the most empowered individuals have only slightly more leverage than the rest of us.

As someone famous[1] once said, there are tides in the affairs of men – tendencies for millions or billions of people to make the same kind of choices at the same time. Those individuals who come to be called ‘great’ are usually those who have had the judgement or fortune to take the tide at its flood. I think we are at the turning of the tide in one important sense: away from the cult of the individual and towards a more collectivist spirit. Call it a hunch, it’s no more than that.

In her 1929 novel The Fountainhead (spoiler alert), Ayn Rand describes the struggle between the highly self-actualised individual, our hero Howard Roark, and the enervating, collectivist establishment represented by the villain of the piece, Ellsworth Toohey. Toohey is obsessed by Roark, consumed with envy, and rationalises that envy by seeing Roark’s individualism as unforgivable arrogance. Toohey makes it his business to undermine Roark’s career (in architecture), going out of his way to trash his reputation and scupper his plans. He succeeds, and Roark is ruined, but continues to do his thing without resentment and without deviation. They meet, and Toohey describes what he’s done and why, and the following magnificent exchange ensues:

Toohey: Mr. Roark, we’re alone here. Why don’t you tell me what you think of me? In any words you wish. No one will hear us.

Roark: But I don’t think of you.

Rand famously detested collectivism of any sort, being more inclined towards the idea of individuals with the necessary drive and single-mindedness overcoming their own limitations and all the vicissitudes of life, including the usually malign intervention of others, to pursue self-actualisation and self-expression to the fullest. Ideas like these were to be adopted and distorted by Adolf Hitler and others of that ilk. Rand is often labelled as a fascist, and there are clear overlaps, but my reading (based entirely on The Fountainhead, so I am doubtless missing a lot) is that she was an individualist: for her, power meant power over one’s own destiny, not power over others.

The struggle between Roark and Toohey is the struggle between individualism and collectivism. History tacks between those two ‘isms’. And it feels as though, for the last couple of decades or more, we have been tacking towards individualism. Not always and everywhere, of course: but that has been the movement of the tide.

One manifestation of this is the dominant genre of blockbuster movies. The spirit of the times is often captured in the movies. Right now, it’s all about superheroes of various kinds. Individuals, maybe loners. Outsiders, overcoming their limitations somehow – gifted with a blessing or a curse of difference from the mass of humanity. They are marked out, in their own minds at least, as ineluctably different. As ‘super’. They rise through difficulties and rejection to prominence, to dominance. Only they have the stuff that the world needs to survive, though often the world is ungrateful and doesn’t realise the debt that is owed to the hero. These are the supermen or women. They rise through their own limitations and then, all too easily, slide into the assumption of power over others, used for good or evil. The only real battles, in this genre, are between the superheroes. The rest of us just watch.

The rest of us are buffeted around by life: we are objects that things happen to.

The superheroes alone are subjects: agents of their own destinies, and ours. They are no longer limited by internal contradictions or by received, common morality. They have risen above themselves and, as it usually turns out in these films, above the rest of us too.

Much to the annoyance of my kids (now in their twenties) I have now reached and passed my point of satiation with movies of this genre. I flat out refuse to watch another one. At least a decade must pass, maybe two, before I will review that position. They are boring. The same themes over and over. The same BS. Boring people doing boring things, aided by immensely boring CGI. I’ve had enough.

Yes, yes, I’m just one curmudgeonly and increasingly old bloke. But indulge me. Just call it a hunch.

Batman is not real (sorry). There are real people who are celebrated and wealthy, and style themselves as outsiders, self-made people. But the truth is, that is not usually because they have been through a struggle to overcome the self, even if they think they have — and even if that thought is reinforced by the many hagiographies that subsequently do the rounds. More commonly, they have been lucky with money, perhaps while working hard and making a few good calls. Or sometimes it’s their very emptiness that is celebrated: celebration of celebrity itself. These people tend to dominate the news cycle, with the same impact on me as the superhero movies. I’m bored. Same ole same ole. Show me something else and it’s just possible I’ll tune into the news again, or even (incredible to report) buy a newspaper now and then. But not at present, thank you: you can keep it.

So it is with economics, too. Is Powell the GOAT, or someone else? I confess I find that kind of question less and less interesting.

Macro trends are the results of billions of choices, moved by huge tides, and nudged (at best) by policy interventions.

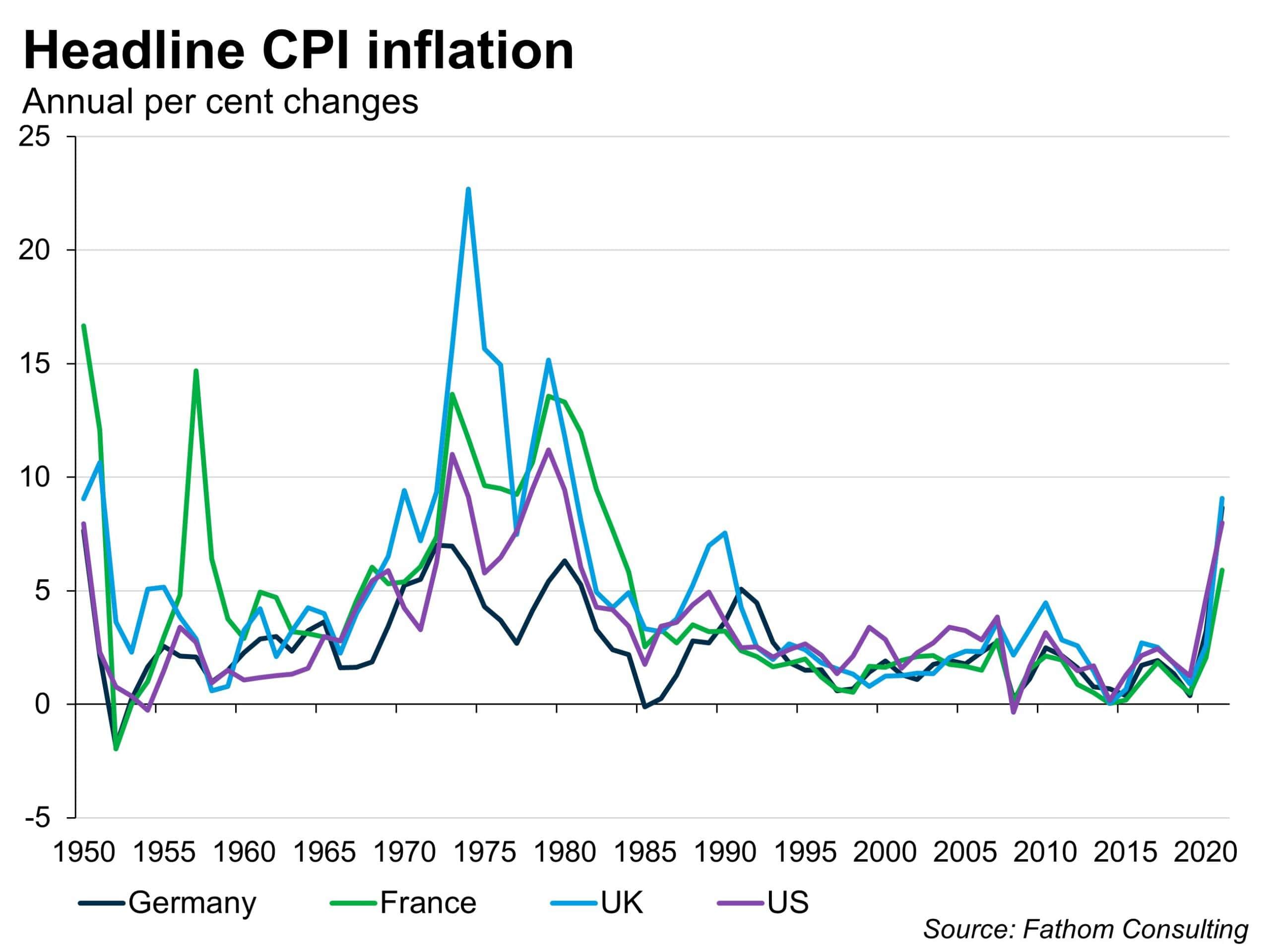

The chart above shows CPI inflation in the US, Germany, the UK and France going back to the 1950s. What is most striking, to me, about this chart is the degree to which inflation has a very similar pattern across all four countries. The tide moves all four; to a much greater degree than the idiosyncratic policy errors or policy triumphs in each one. For the most part, inflation (like other macro variables) is ‘received’, not created or destroyed by great people – their influence is only visible at the margin.

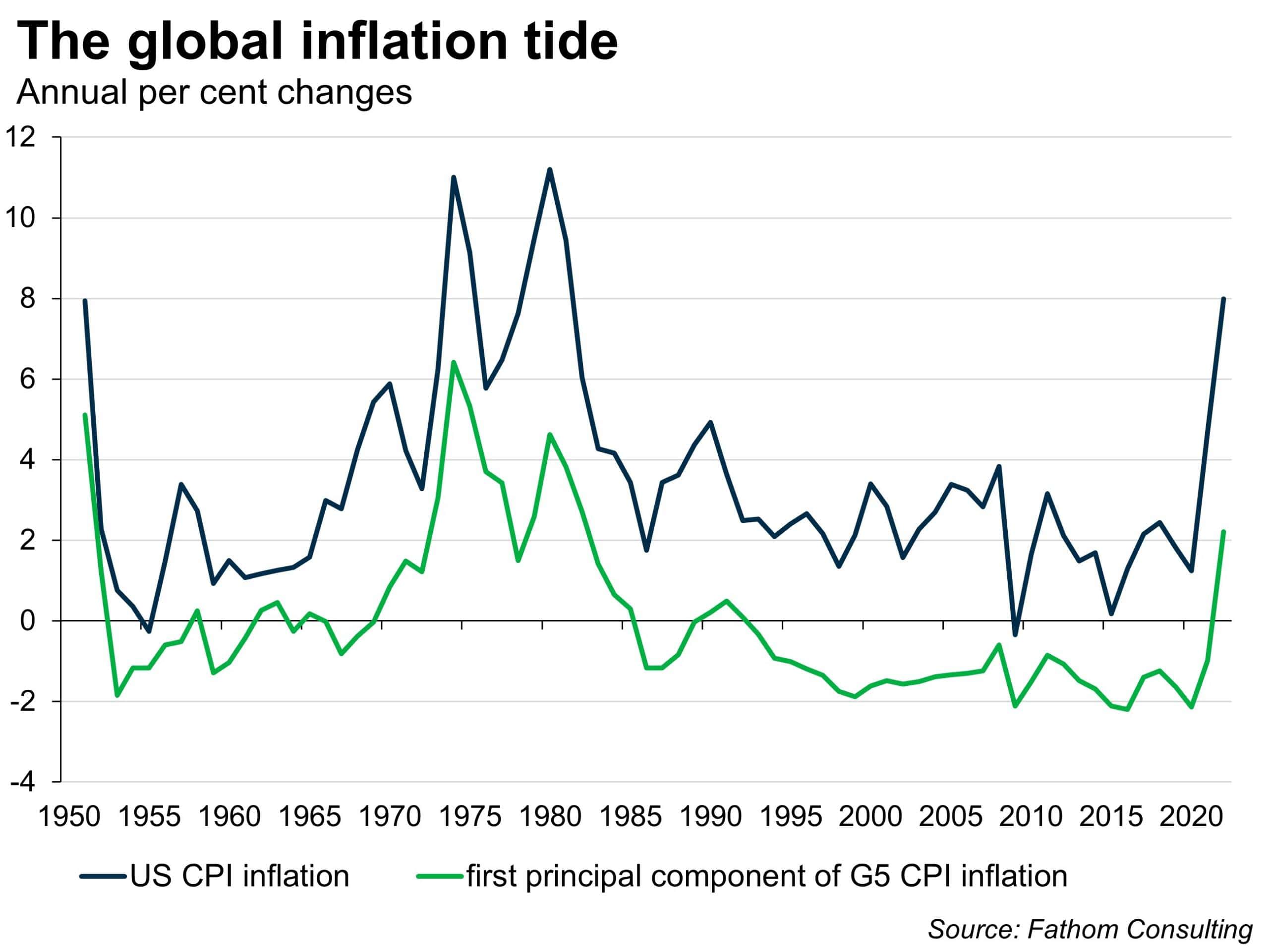

In the case of inflation, the first principal component of inflation across Germany, France, the UK, Italy and Japan (which we can think of as the global inflationary ‘tide’) explains 75% of the variation of inflation in the US since 1950 (in a model that also includes a constant term and the lagged dependent variable). The global tide is pictured alongside actual US inflation in the chart below. The difference between the two, in a sense, captures (amongst other things) the role of the Fed in influencing inflation outcomes in the US. Who is the GOAT? It’s pretty hard to tell.

Of course, this is headline inflation in the US and the first principal component of headline inflation in five other countries. In all cases, the headline numbers are moved by common trends in, for example, commodity prices. I understand that. The bit that remains is the idiosyncratic part and, don’t get me wrong, I understand why it’s important to study that part as best we can.

Going there, it turns out that about a third of the idiosyncratic part of headline inflation in the US can be explained by a constant and by the lagged percentage deviation between GDP and a deterministic time trend: by the Phillips curve, in other words. But two thirds still remain unexplained, and the unexplained component is not just white noise. It is serially correlated, distributed non-normally and exhibits heteroskedasticity too. That’s where you’ll find the role of policy. If there’s a GOAT of the Fed, that’s where you’ll find them lurking: reducing the variance of that component, shifting the mean towards zero or, even better, towards a pattern that is negatively correlated with the global tide. The GOAT will demonstrably pull against the tide.

But the tide remains the dominant force. In the current conjuncture particularly, it’s the tide rolling through inflation everywhere, first and foremost. The role of policy is slight: slightly better in the US than on average; slightly worse in the UK. It feels to me that the focus on the personalities of the policymakers, on the colour of tie they are wearing, speculation on what mood they are in — all that stuff — has been de-emphasised, correctly. It feels as though we understand that there are much bigger forces in play than the fine-tuning that these individuals can achieve at best.

What moves the tide? Billions of choices around the world. The principal component of GDP across the developed world is a good predictor of the principal component of global inflation, with a one-year lag (the Phillips curve kind of works globally, too) – but the part that remains unexplained has strong momentum (the residual depends on its own lag with a coefficient of 0.8). The tide, once it gets going, is strong. As King Knut demonstrated, there’s not much that anyone can do to resist it.

That realisation, of the relative impotence of individuals no matter how empowered they might be, in the face of strong tides that result from billions of choices that generate their own momentum, resonates beyond macroeconomics. Individuals are interesting, but only up to a point. We should also pay attention to the tides in the affairs of men. And, tentatively, I think that is maybe what we are doing.

To be clear: I do not mean that we are all completely impotent. No: each individual has weight, albeit a small weight, and some have more weight than others. It is vital for social progress that the individual should make use of such influence as they have. It is usually close to zero for most of us but, crucially, not actually zero. And there are some individuals who are either gifted or exceptionally focussed and driven in certain fields (or both) – one thinks of elite athletes, international opera singers or, indeed, leading economists. It is glorious to see people at the top of their fields do their thing. Some of what passes for collectivism is often an expression of envy towards these individuals: that is when the collectivist spirit has over-reached itself. Collectivism in its helpful phase is not about cutting down the tall poppies, but about remembering that there is also the field to consider.

The individualist portrayed by Rand is not narcissistic. Roark doesn’t care about what other people think of him. He just knows what he wants to do and goes ahead and does it. He wouldn’t stoop to court public opinion, and he would dismiss market valuations of his efforts as irrelevant. The self-styled supermen who dominate the news are narcissists. Unlike Roark, they want to know what we think of them. The correct response is Roark’s response to Toohey. We don’t think of them. We have better things to do.

[1] For the pedantic: Julius Caesar, Act 4, Scene 3, line 218, Brutus — ironically, shortly before his defeat and suicide.

More by this author