A sideways look at economics

Renowned economist, Alex Edmans, recently presented to Fathom on the topic of bias in data. One example cited a study that claimed breastfeeding leads to more intelligent babies. Delving further into the study, mothers with higher education and more supportive home environments were more likely to breastfeed, meaning that the correlation could be due to the mothers’ home environments rather than breastfeeding itself. That the underlying data is, first, correct and, second, analysed in a non-biased way, is crucial in research. For a macroeconomic consultancy such as ourselves, it’s at the centre of what we do. We never claim to know 100% of the truth, though our aim is to get as close to the truth as possible. That does not mean that we are never subject to bias. In fact, I recently came across an article about flawed data in blue zones, a topic I covered in a TFiF not too long ago.

Blue zones are areas of the world with the highest healthy life expectancy and a high probability of reaching 100. Five blue zones have been identified in the world — the Barbagia region (Sardinia), Ikaria (Greece), Nicoya (Costa Rica), Loma Linda (US) and Okinawa (Japan). In a popular Netflix series, a new blue zone is visited in each episode, as they try to explain why people in these zones live longer lives. Common traits across the blue zones are eating non-ultra-processed foods, a sense of purpose in life, moving ‘naturally’ (e.g., living on top of a hill or doing gardening every day), and connecting with the local community. One thing that I found particularly interesting, and pointed out in my TFiF, is that blue zones are not located in particularly wealthy areas, going against the global trend of higher income leading to higher life expectancy.

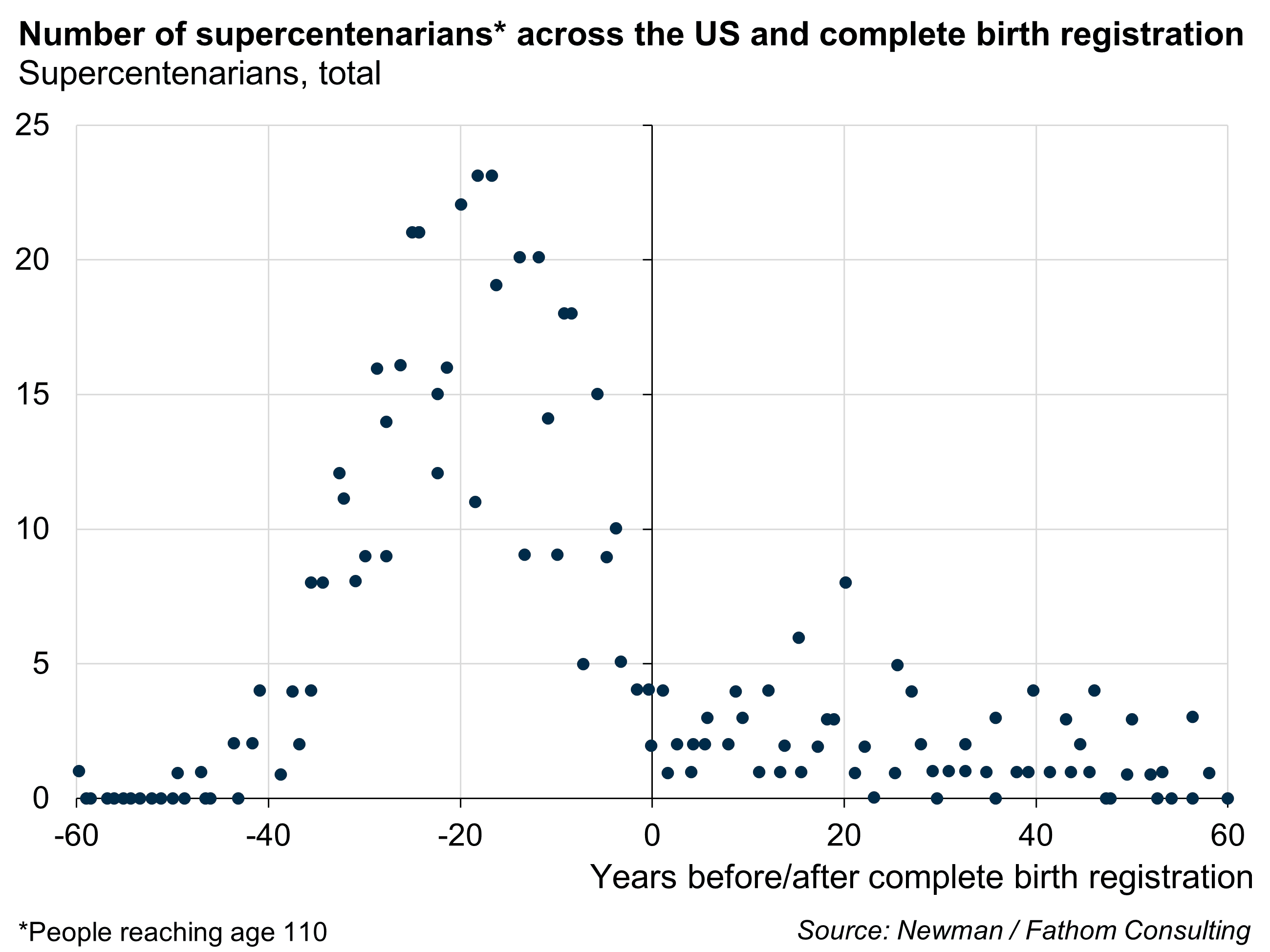

However, there may be another reason behind the blue zones going against the global trend; errors in data. In his research paper,[1] Dr Newman (UCL Centre for Longitudinal Studies), looking at data from the US, France, Japan, England and Italy, finds that indicators usually associated with shorter life expectancy, such as low income and poverty, are positively correlated with the share of people reaching the ages of 100, 105 and 110. Looking at the probability of survival at every age below 90, he finds the opposite effect. In the US, after the introduction of state-wide birth certificates, the number of people above 110 fell sharply (note that the US as a whole is not a blue zone). According to Newman, Sardinia, Okinawa, and Ikaria correspond to regions with low incomes and short life expectancies relative to their national averages. He claims that the underlying data for blue zones may contain errors, perhaps in certain cases motivated by pension fraud.

Loma Linda, one of the blue zones with a very high average life span, was found to only have an average life span according to independent estimates by the Centres for Disease Control. The Nicoya blue zone’s old-age life expectancy turned out not to be extraordinary, after it was uncovered that 42% of Costa Rican citizens over the age of 99 had mis-stated how old they were in the 2000 census. In 2010, 230,000 Japanese people over 100 years old were found to be “missing, imaginary, clerical errors, or dead” (Newman, 2024). Furthermore, in 2012, 72% of Greek centenarians were, in fact, dead, likely due to pension fraud.

There may still be lessons to be learned from blue zones. For example, Newman’s study does not go into detail about Ikaria, Greece. Furthermore, the author’s debunking of Okinawa seems to focus on current data on the population’s health, which has been deteriorating in recent generations. Newman focuses on data on centenarians and supercentenarians in the US, France, Japan, England and Italy, which cannot be used to make assertions about all blue zones. Finally, the blue zone project did undertake data verification itself — they travelled to the blue zones to cross-reference available documentation. However, Newman’s paper does point out errors in the data of the blue zones of Loma Linda and Nicoya, and highlights the issues of finding credible longevity data.

It looks like the blue zones project and Newman’s paper may both be subject to confirmation bias, which is when one interprets data based on existing beliefs. According to Edmans’ presentation, when presented with information that counters your existing beliefs, the same part of your brain (the amygdala) is activated as if you were to be attacked by a tiger. The blue zones project, in its mission to seek the truth behind blue zones, and why people there live longer and healthier lives on the one hand, and Newman in his mission to debunk the blue zones, on the other, may have been subject to such bias. I was as well — when watching the Netflix documentary on blue zones, and saw the remarkable effects that implementing the results of the blue zones project had on areas in the US, as well as the touching stories of the elderly interviewed, I wanted to believe that the underlying data was true.

So, why is it important to avoid bias? Generally, it is unethical to present wrongful data, as this can have implications for people’s decisions. In the case of blue zones, claiming that blue zones are fake news (Newman) on the one hand and claiming to have the recipe for longevity (blue zones project) on the other, casts doubt about what factors lead to long lives, which can affect the measures and decisions people take to live healthily. Furthermore, one of the indicators that governments look at when allocating money is the share of the population that is of an older age. If the underlying data is wrong, this may lead to wrongful distribution of government funds. From Fathom’s point of view, it is crucially important that we check whether the underlying data for a project is credible (e.g., through a verification process, as we do for our Capital Flows Tracker), and that one person’s view on a topic does not affect the analysis (e.g., through multiple peers reviewing each research piece). These processes are important to ensure clients receive the full picture, and not just the assumptions of one person.

[1] https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/704080v3

‘Thinks and Drinks’ and the sunk cost fallacy