A sideways look at economics

Everyone loves a rogue. Think Han Solo in Star Wars, Jack in Titanic, Hilts in The Great Escape, and the Artful Dodger in Oliver Twist. And the popularity of silver screen rogues hasn’t gone unnoticed in the world of politics, where in recent years we’ve seen comedian Beppe Grillo, leather-clad Yannis Varoufakis and scruffy-haired Boris Johnson all array themselves in the mantle of anti-establishment rule-breakers (some more convincingly than others) in their bid for high office. Sooner or later, all of them fell from grace. But is there a deeper value to the notion of breaking the rules?

In economics, there’s a lot of debate as to the merits of unorthodox policy, but the orthodox position is that it’s a bad thing.[1] (Hard to ignore the possibility of bias there.) We do, certainly, have two current examples where breaking economic rules has gone horribly wrong:

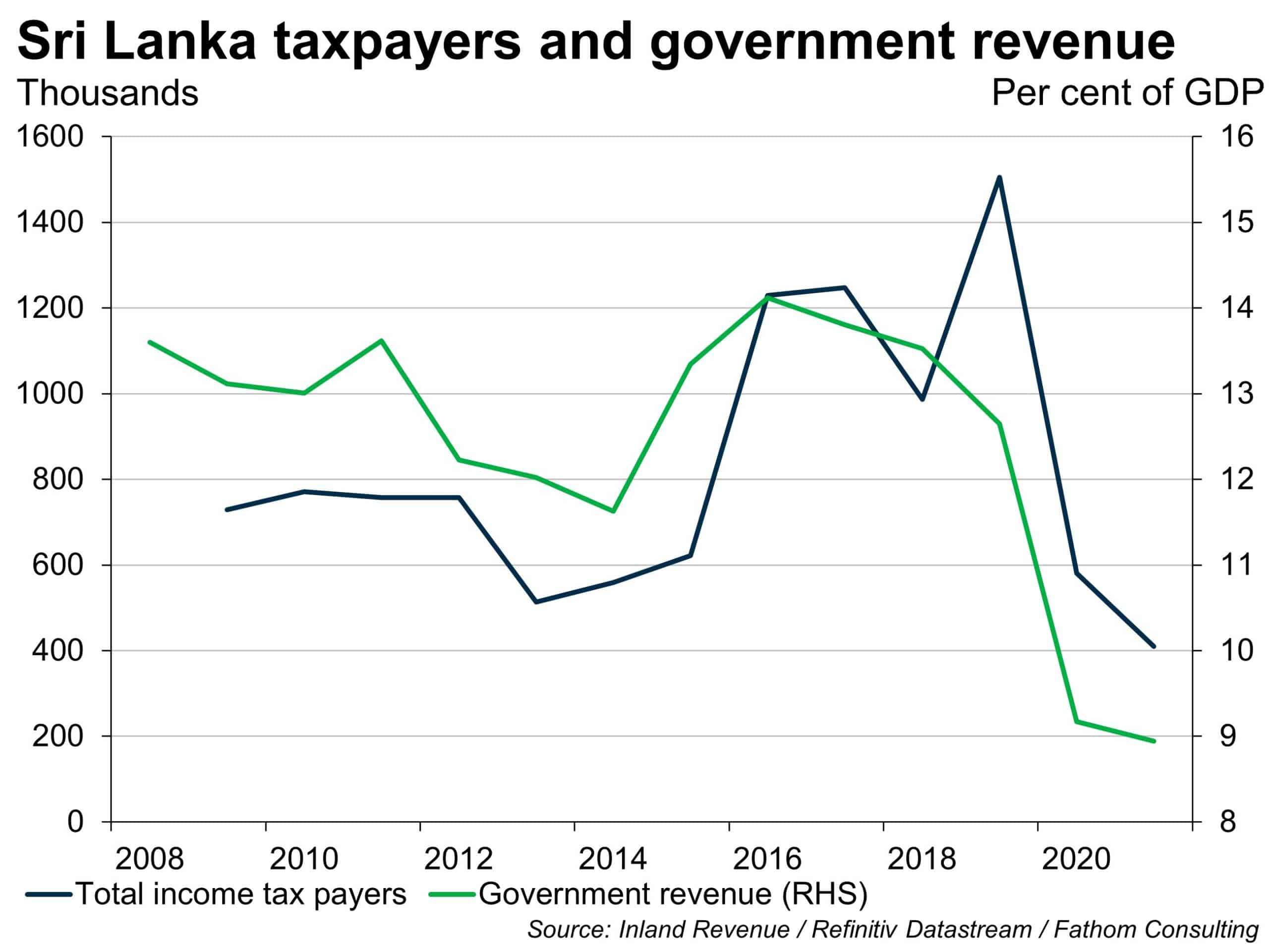

- Sri Lankan fiscal policy: Sri Lanka offers us a cautionary tale as to the consequences of abandoning fiscal orthodoxy. President Rajapaksa’s government cut tax rates shortly after coming to power in 2019. They did this despite pre-existing questions regarding debt sustainability. While there is conceptually a possibility that cutting taxes can increase government revenue (by increasing economic growth and incentivising people to work more), the orthodox position is that this doesn’t hold in practice. Estimates suggest that the number of Sri Lankan taxpayers fell dramatically following the reforms — think how much more tax the remaining taxpayers would have had to pay in order to offset that. Unsurprisingly, the sovereign has subsequently defaulted on its debt.

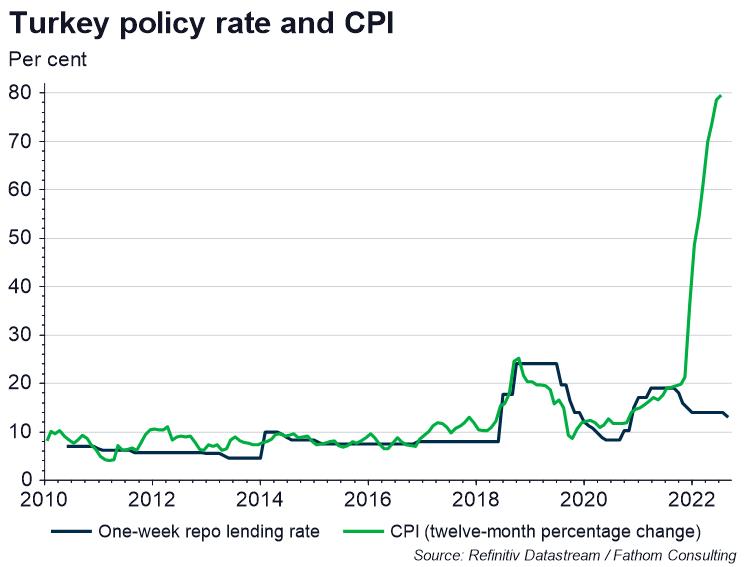

- Turkish monetary policy: if Sri Lanka offers a warning for fiscal policymakers, then Turkey offers one to central bankers. Under pressure from President Erdogan, the country’s central bank began cutting interest rates last year, despite high and rising inflation, arguing that higher rates cause high inflation. Economic orthodoxy argues the opposite, and would have supported raising rates, not lowering them. Less than twelve months later, the country faces inflation close to 80%, up by around 60 percentage points. Economic activity hasn’t collapsed yet (possibly due to the multitude of crisis-fighting measures the government has deployed) but this seems unlikely to last.

So, should we always stick to the rules? Certainly not. John Maynard Keynes famously quipped that he changed his mind whenever the facts changed. He was right — we should always be looking out for new ideas, new theories, new policies. And when we find them, we should rewrite the rulebook. This ‘out with the old, in with the new’ approach underpins Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction which argues that a large portion of economic growth can be explained by the continual death of old firms and the birth of new ones. Stifling that cycle (a process known as zombification) reduces short-term business-cycle volatility but also harms long-run economic prospects. In other words, it produces a simultaneous reduction in both risk and reward. These effects accumulate over time and can be extremely large — for instance, a 0.9 percentage point drop in labour productivity (the fall the US experienced between the 2000s and the 2010s) would leave the level of productivity around 10% lower after ten years.

Most of the time, it’ll be the rogues that break up the old rules-based order. They are the disrupters and insurgents. But a tendency to break the rules means they also increase the odds of trouble further down the line. This leaves two options — either focus on the risk (i.e., back the rogues less) or focus on the rewards (i.e., back the rogues more). That choice should be very familiar to anyone who’s ever thought about how they invest their savings. Obviously, some rogues are only likely to breed chaos (think Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker) while others are playing high-stakes games that’ll either end in success or disaster (think Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games). Never pick the former — it offers high risk with little reward. You might pick the latter. Economics cannot tell you whether you should — that is a choice for you to make.

More by this author

[1] In an influential paper, Dornbusch and Edwards laid out what they describe as the four common phases of populist policymaking from a macro perspective. These phases are:

- Phase 1: Newly-elected governments are proactive and set about tackling the issues that led to their election. Aggregate demand rises and so does output, wages and employment. Great!

- Phase 2: The economy begins to hit bottlenecks as it becomes apparent that the increase in demand is not sustainable. Inventories are depleted, prices start to rise and the exchange rate begins to fall. Not so great…

- Phase 3: The economy’s problems intensify with inflation hitting double (and sometimes triple) digits and the value of the currency plummeting. Tax revenue drops and there is a fiscal crisis. Very bad.

- Phase 4: The government is replaced and fiscal stabilisation typically follows, often with the aid of an IMF bailout. The economy begins to recovery, slowly.