A sideways look at economics

The Fathom team is just back from our annual getaway, which we spent in Hinwick House – a stately home on the Northants/Bedfordshire border that offers a mish-mash of 18th-century architecture, antique memorabilia of various vintages, stuffed animals, expensive-looking silverware and vases, an in-tune grand piano, and a truly surprising number of bugles in all sizes. The décor suggests a storied past full of foxhunts, servants and white-tie dinners – think Bridgerton. Most of those stories are however buried in nostalgic pastiche, with many bits and pieces of stuff from history but less of what actually happened in that house. The getaway was grand for all that, and the house very accommodating and enjoyable. Nostalgia is looking at the past rose-tinted, which this house very much encourages you to do. One of the exercises we did at the getaway was to take a more clear-eyed look at our own past, removing the rose tint. When was the best time to be alive? And what are our main concerns for the future?

The best time to be alive is right now.

That is borne out in global data: the average real standard of living is higher than ever, inequality is lower than ever, infant mortality lower than ever, risk of violent death at an all-time low, levels of education at an all-time high, gender inequality lower than ever, the risk of death from extreme weather events is at an all-time low, the human population is higher than ever and reaching a stable plateau, and so on. The human species has never had it so good. [1]

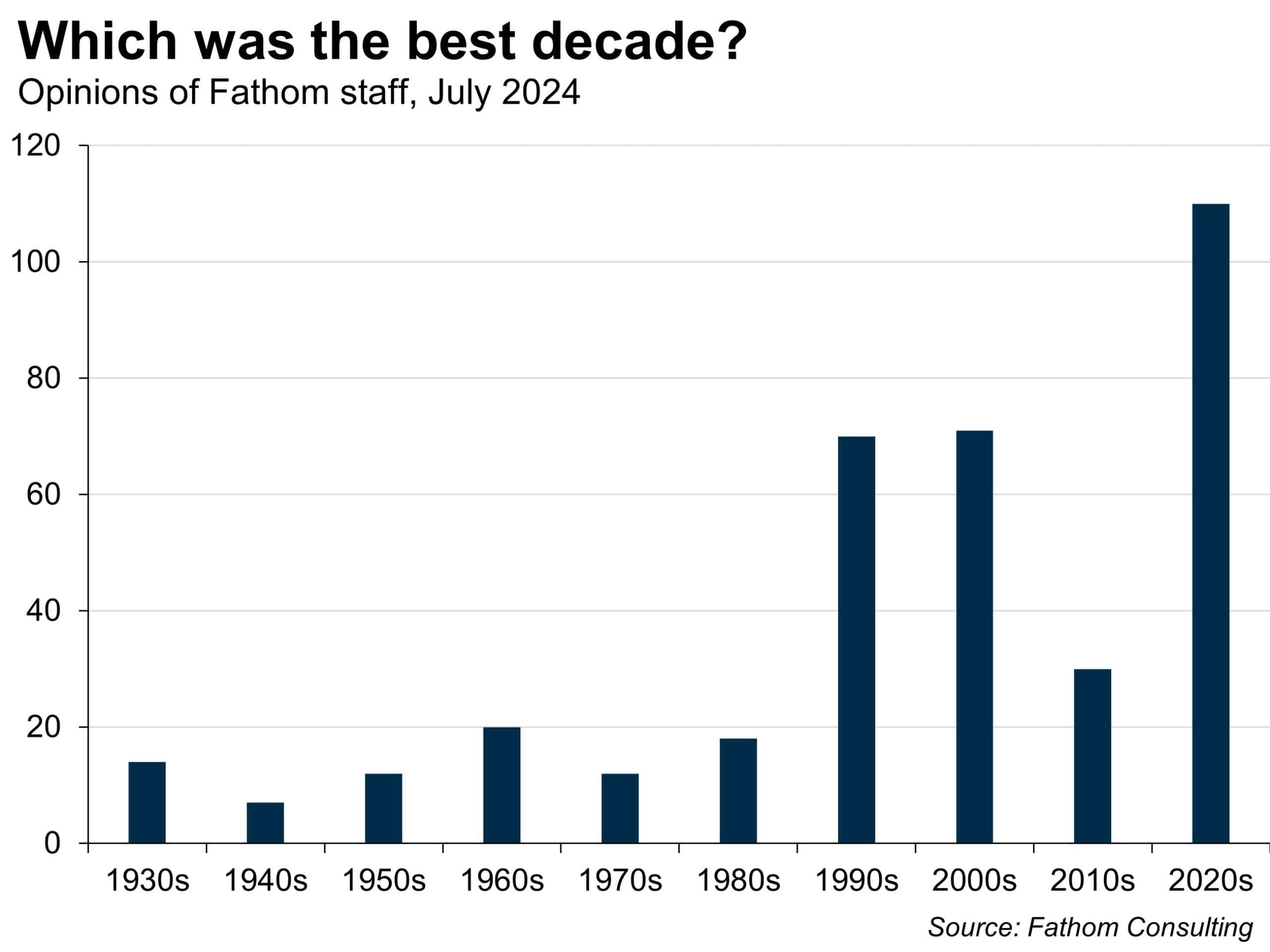

And it’s borne out in responses to a survey of Fathom staff too. The most-favoured decade among Fathom staff on average across the 13 categories we explored is the decade we are now in.

No wonder we’re all so happy.

Just joking. Maybe the disconnect between Fathom’s view, the global facts and the sense that we’re not as happy as those facts suggest we ought to be, comes from this: there are interesting differences in the survey responses across categories. What kind of things are best now? Which were best in the past? In particular, does everyone tend to think the period in which they were growing up as the ‘best’ period in some categories, as suggested by this survey?

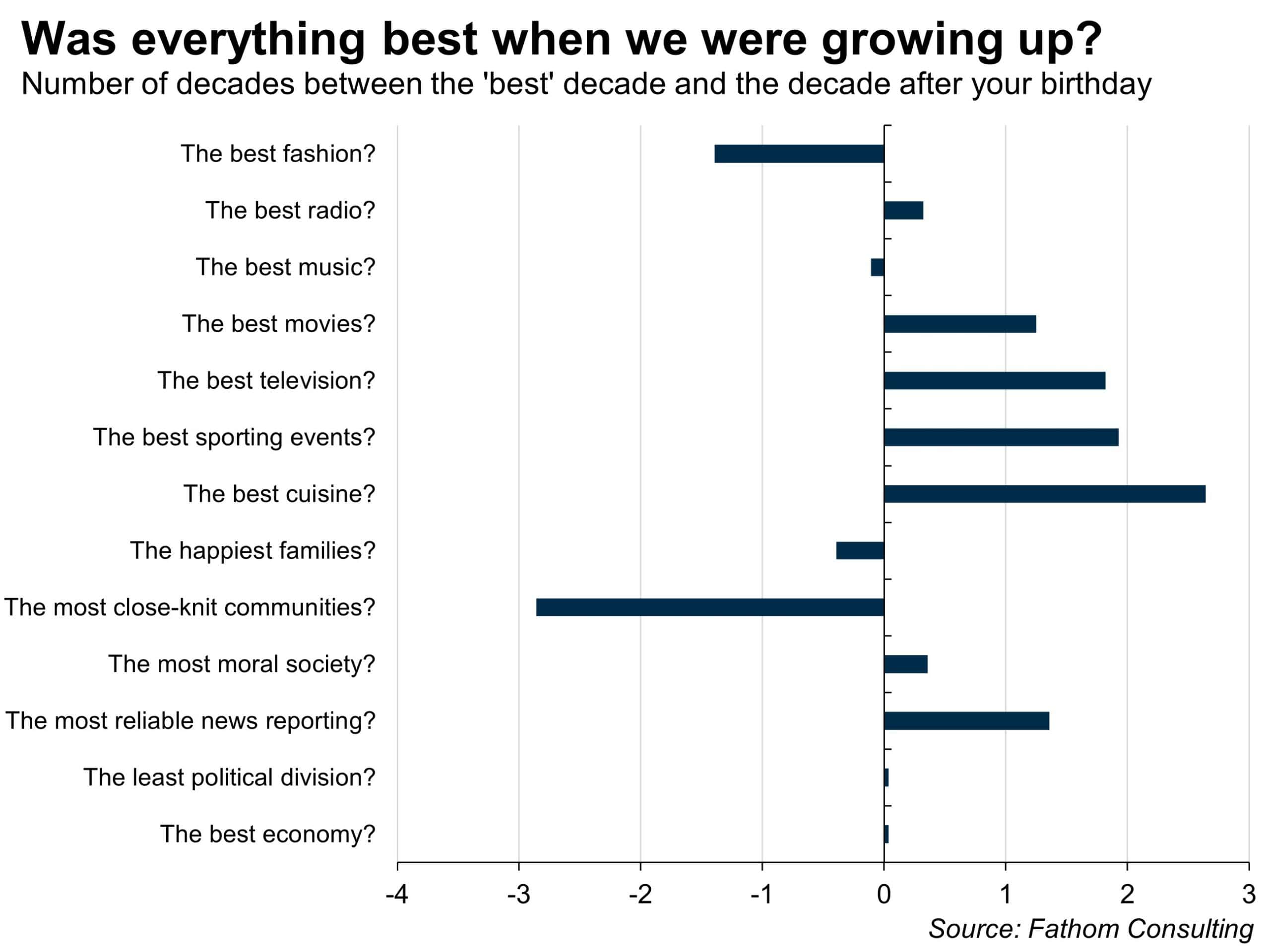

The chart below shows that Fathom staff tend to believe we were best-dressed, happiest as families and closest-knit as communities in the decade in which we were born or earlier than that; that the best music, the best economy and the least political division were in the decade in which we grew up (the decade after the one in which we were born). But everything else has got better since then: TV, film, sports, cuisine, morals and (surprisingly to me) the reliability of news reporting.

Maybe the sense of missing happiness springs from that difference. Could it be that close-knit communities and happy families contribute more to our well-being than good sports, TV, movies and the like? Sounds plausible.

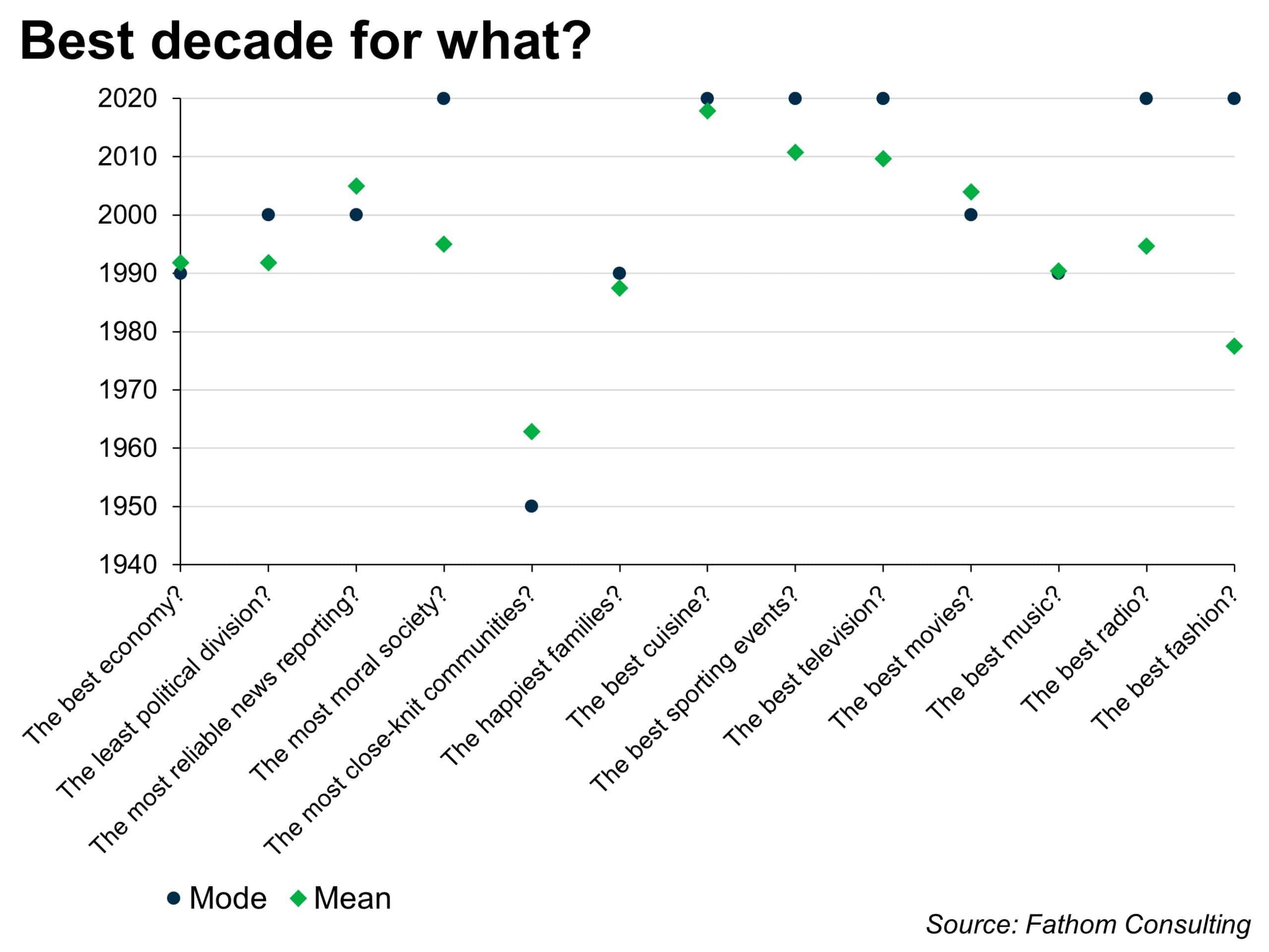

Even so, it does not detract from the fact that the current decade is judged the best overall. The chart below shows the mean and mode ‘best’ decade for each category, and the 2020s wins in 6 of the 13 categories.

Some of these categories would probably have had a similar structure no matter when this survey had been taken. The best fashion? It’ll be whatever people are wearing now, probably. Ditto the most moral society: it’s hard not to implicate oneself in a judgement that society is immoral – or it would be odd if that were the average feeling. Not impossible, of course, since the average person believes themselves to be an above-average driver, for example. And if we did not think now had the best cuisine, the best TV, the best movies, then that would point to a clear arbitrage opportunity that could easily be exploited. That said, my own memories of the 1970s was that the ‘cuisine’ of the time, if you could call it that, was so awful that almost any previous cuisine, real or imagined, would have been better. And I remember a scene in the 60s movie The Ipcress File where Michael Caine’s character is called a ‘gourmet’ on account of having selected a tin (yes, a tin) of ‘champignons’ from the unrelieved rows of tins that constituted the entire offering of the supermarket he was visiting with a colleague. Happy days.

The category ‘Most close-knit communities’ stands out to me. The mean and mode are both well before most Fathom staff were born. This response has a strong whiff of nostalgia about it to me – a feeling that in this important sense life was ‘better’ in some imagined past. Better? Well, different. To me, ‘close-knit’ can be read in two ways. It speaks of supportiveness and cohesion, the feeling that one is not alone and will be noticed and cared for by one’s neighbours. But it also suggests control and lack of mobility: one has to make the best of whatever one is born into, no matter how restrictive or authoritarian that might be. It’s not clear to me whether living in a more close-knit community would contribute positively or negatively to my happiness. A bit of both, probably, netting out at zero.

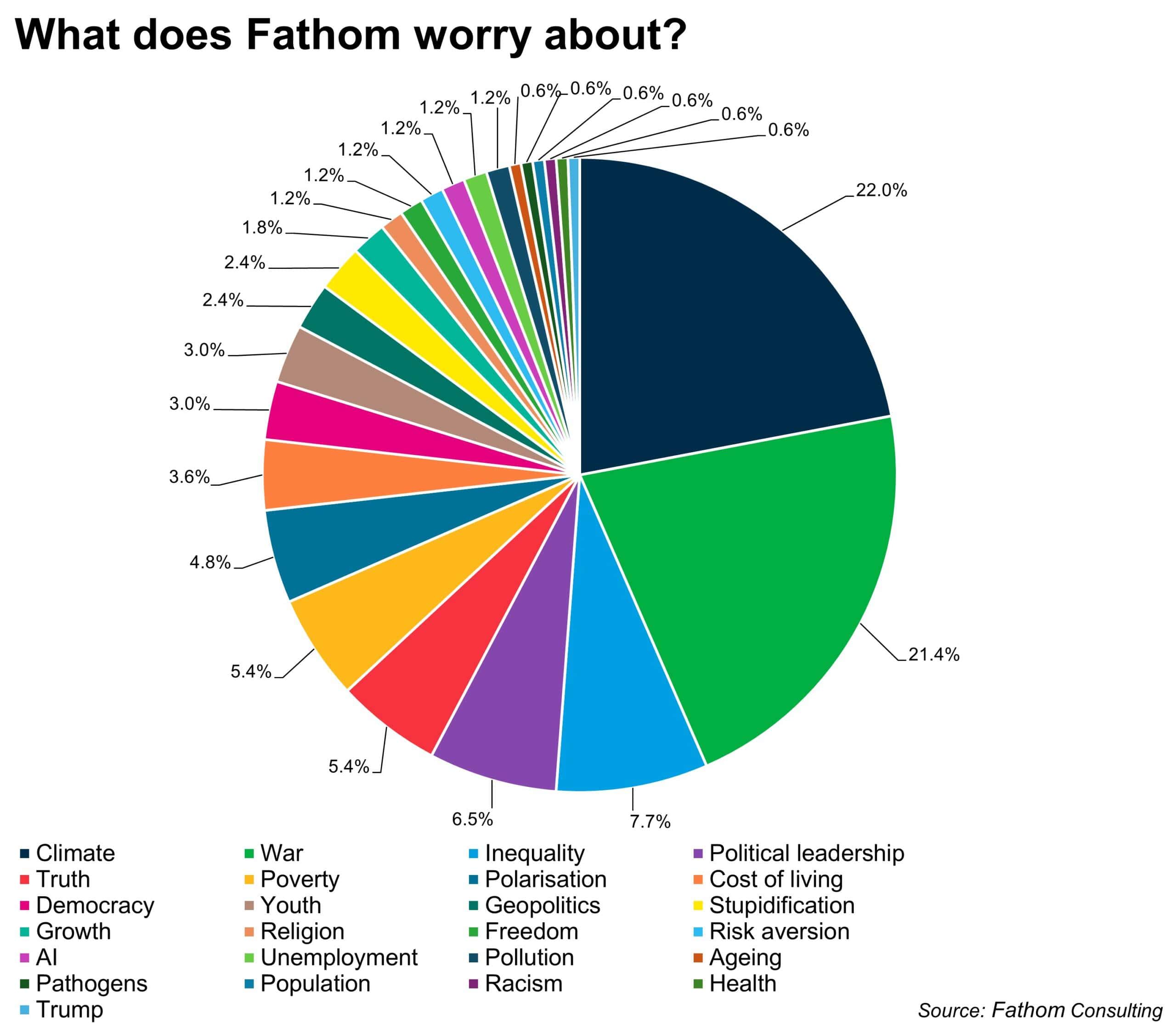

But one’s wellbeing is not just about where things now stand. It also involves judgements about how things might evolve in future. Another question we asked of Fathom staff was to name the three issues that most concern them in the world right now. The answers (weighted by the importance attached to each question) are captured in the chart below.

Risks to the climate and the risk of war are the top two concerns among Fathom staff, far ahead of any other issues. These issues loom large for either or both of two reasons: the risk of something bad happening is judged to be high; and the impact if that were to happen is also high (and negative). So the best decade (now) is fraught nevertheless with a sense of possible impending doom. Perhaps that is the reason for the perception of a happiness deficit?

I think not. I am older than most people at Fathom, and I cannot remember a time when there was not an air of impending doom. And the literature I have read suggests that same sense has inhabited all ages. I think it is part of the human condition and a consequence of progress. It feels unreal that life now is so sweet compared to the past, for a large and increasing proportion of the species. It feels like something big is bound to go wrong. Surely some revelation is at hand? Surely the other shoe will drop?

Maybe it will; maybe it won’t. But I’m not sure the risk is bigger now than it was when, for example, the USA and the USSR were on the brink of all-out nuclear war; or when the fascists were in government in mainland Europe; or when Marx and Engels were writing about the conditions of the industrial working classes in Britain; or when the Spanish flu killed more people than the Great War that preceded it; or at many other equally grim periods in history.

That perspective might come from my relative age compared to other members of Fathom staff. Those of us born in the ‘60s are generally a little more concerned about the climate than the Fathom average, but a lot less concerned about war. Certainly, it does not appear to reflect my role in the company: in the management team (of which I am one) the proportions concerned about both war and the climate are even larger than across the rest of Fathom. I guess I’m an outlier.

Final provocative thought from an outlier: the world is a risky place, as it always has been. But for most humans alive right now, the risks are substantially smaller than they have been at any other point in human history. Maybe that’s the problem for the increasing proportion of humanity for whom historically prevalent risks have, so far, diminished? It doesn’t feel real. It feels like payback is due. Maybe that’s the source of the happiness deficit?

As the perennially anxious earthworm said in Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach: “The problem is… the problem is… well the problem is that there is no problem.”

Dinner at Hinwick House

[1] Please do not infer from this that I believe human suffering to be trivial or non-existent currently. There is still an enormous amount of avoidable suffering which is not tolerable and should be addressed as a matter of urgency. That is true in my opinion and in no way contradicts the statement above.