A sideways look at economics

Cities across the US have faced days of protests following the death of George Floyd after a distressing video of a Minneapolis officer kneeling on his neck for eight minutes and 46 seconds was released. It was the latest example of an unarmed black man being killed by a law enforcement officer. The #BlackLivesMatter movement was sparked by outrage at police brutality, but it speaks to a broader set of injustices faced by African-Americans, including inequalities in economic outcomes and lived experience.

The struggle for black people to receive equality in America has been long and painful. The first slave ship arrived in Virginia in 1619, with legal emancipation not arriving for 246 years, when Congress passed the 13th amendment. Legal discrimination endured for almost another century through the ‘Jim Crow’ era of enforced segregation, which led to the civil rights movement. It wasn’t until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that discrimination on the basis of race was made illegal. In 2008, Barack Obama was elected as the country’s first black president.

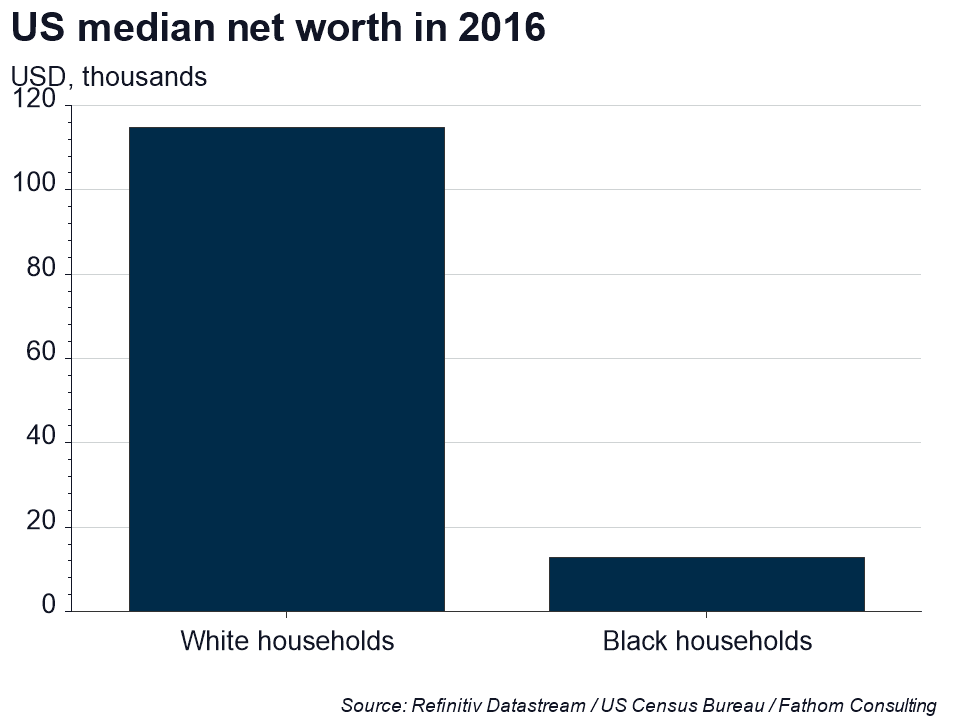

Despite significant progress over the past few centuries, a substantial gap in economic outcomes between races endures. The net worth of an average white household today is nine times greater than that of an average black household. Surprisingly, that ratio has barely budged since the early 1960s, before the Civil Rights Act was passed. Putting to one side the clear issue of justice, this represents wasted potential. As with the gender pay gap, even a cold economic assessment would argue for closing it.

Finding solutions to a problem is always easier when you have a better grasp of its roots. But there are differences among economists on the precise cause of the racial wealth gap. One school of thought is that it reflects a longstanding racial income gap. The median black household earned $41,361 in 2018, versus a $70,642 median income for white households. Cleveland Fed research suggests the racial wealth gap would have mostly disappeared between 1962 and 2007 in the absence of differences in income.

Meanwhile, researchers at the Brookings Institution find substantial gaps in wealth even once you account for differences in income. For example, white households in the top 10% of the income distribution have an average net worth of $1.7 million. That contrasts with a $343,000 figure for black households in that same bucket. They point to research by economists Darrick Hamilton and Sandy Darity that finds that inheritances and other transfers “account for more of the racial wealth gap that any other demographic and socioeconomic indicators”.

But it’s not just economics. Distrust and even fear of police officers is symbolic of a diminished lived experience. The Harvard Economist, Roland Fryer, has found that (controlling for a range of factors), police officers are much more likely to use non-lethal physical force when dealing with blacks and hispanics. That inequality in treatment may surprise some but it doesn’t surprise me. As a teenager in Washington DC, I had guns drawn on me in my own living room after a neighbour confused me with a robber and called the police. It’s hard to account for instances like this, and the many other forms of bias that black people face. At times they make you angry. At times they hurt. More than anything, they weigh on you.

Movement towards racial justice requires progress on both economic and non-economic fronts. If it is income that matters, efforts to improve access to education and to professional opportunities seem like a no-brainer. Meanwhile, racial differences in inheritance suggest an additional reason to think about taxing wealth more heavily than is currently the case. To the extent that current economic outcomes reflect a history of discrimination there is merit to exploring reparations. Of course, protests alone won’t improve the relationship between communities and the police, but they could lead to the implementation of policies that do. Finally, an open discussion about the inequities that minorities continue to face will lead to greater societal awareness, as happened following the #MeToo movement. In time, that should result in cultural change.

I have an Ethiopian mother and Irish father, and grew up in different countries. The US, a diverse nation of immigrants, is the one where I felt most at home. I am in London now, but I plan to return as soon as possible to lead Fathom’s US office. Despite the current situation, I share the view of Martin Luther King Jr that the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice. That doesn’t mean that he sat on the sidelines and just waited for it to happen. The actions of individuals can hasten that process. While the scenes we are witnessing are hard to watch at times, they are also inspiring, and may end up bending a different kind of curve than the one we have recently become used to.