A sideways look at economics

I had a few friends over for dinner last Saturday, with them all kindly taking the time to travel down to my home in Guildford, from London. It was a nice evening, we had a good chat, and enjoyed some food and wine. It was only when I was clearing up at the end of the night that I realised I was left with more wine than I started the night with! And, that got me wondering, had I turned a profit from the evening?

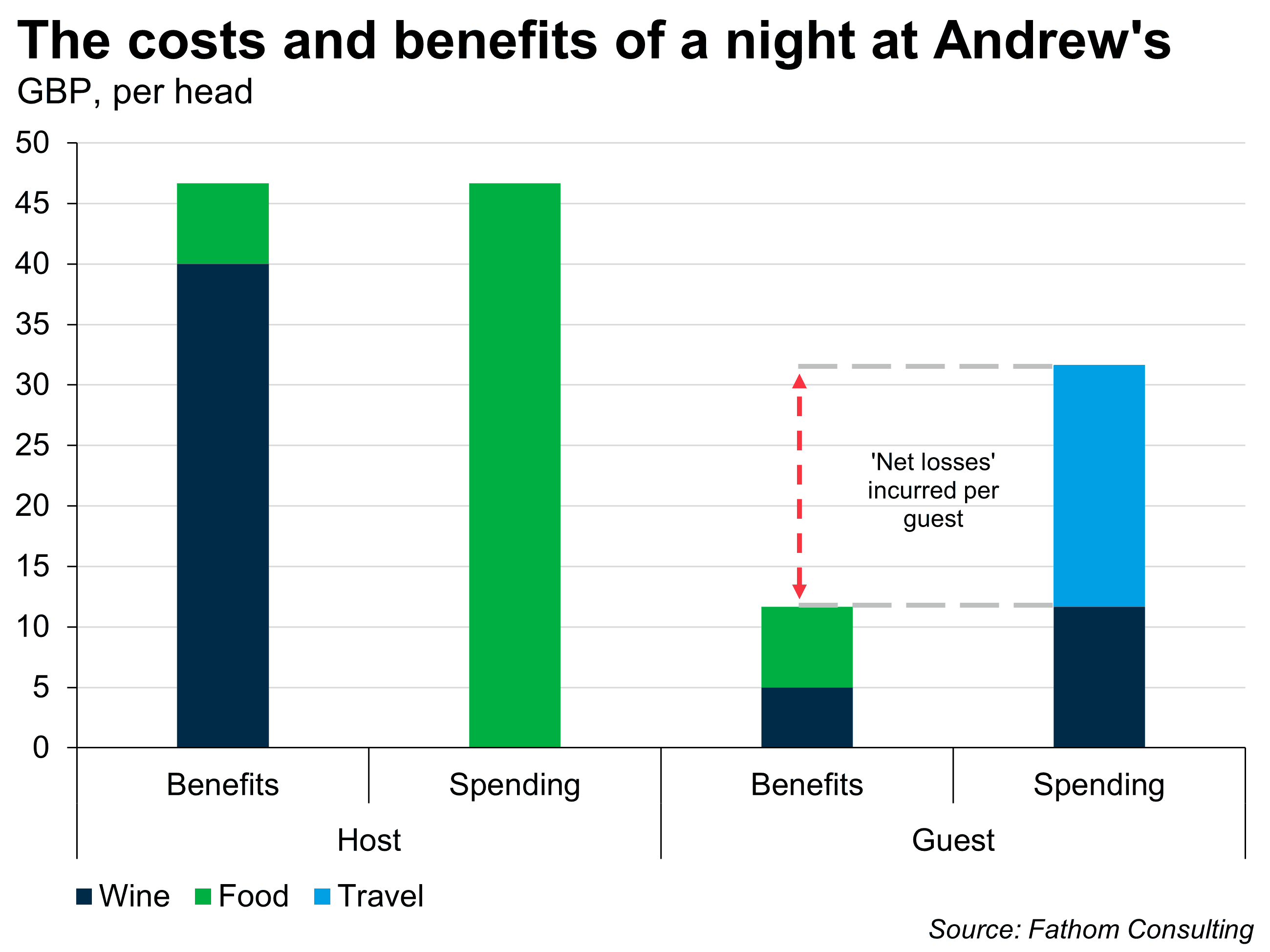

In the UK, it’s customary to bring a bottle of wine to dinner. Two, if you’re feeling extra generous. Saturday’s guests brought seven bottles between six of them, but interestingly we only drank half of that (about half a bottle each). In other words, half of what they bought became a donation to my own wine collection. If we assume (for calculation’s simplicity) that each bottle of wine cost £10, then I received £40 in wine ‘revenue’ (the three and a half bottles left over, plus the half bottle that I drank on the night). Nice!

Of course I can’t treat this all as profit. I need to set that against the cost of the food I provided. To be honest, I have no idea how much I spent on that, but provided that the total I did spend (net of the amount I ate and the leftovers) was less than £40, then I’d be quids in. I think it’s also worth noting here that dinner party food (or at least the kind that I provide, which was mainly assorted nibbles) probably has a diminishing marginal cost — i.e., you need to buy a variety of snacks, which implies a large initial cost for the first guest, but which diminishes sharply as the number of guests rises.

But let’s also flip the problem and view it from my guests’ perspectives. Assuming that I did supply them with my breakeven value of food, would they have broken even for the night? From a monetary perspective, no — especially once travel costs are accounted for. I live in Guildford and my guests all live in London. It cost them about £20 each to travel to my house (and that’s not counting the time it took them to get there, something they most certainly moaned about). As a result, they’d have been suffering a £20 cash deficit. They must have been really keen to come over!

Equally, by hosting I avoided incurring my own travel costs (again, this would have been about £20). But here’s the really interesting point: assuming that we were all indifferent about who hosted, and about the hassle of travelling, what would the optimum dinner party arrangement have been from our group’s perspective? Well, since they spent a combined total of £120 coming to visit me and I could’ve spent just £20 visiting them, the group must be a combined total of £100 down as a result. Imagine instead that the group jointly subsidised me £3.33 each to travel to them. I would’ve been indifferent between that outcome and hosting, and they still would’ve spent less money. In fact, I could’ve asked them to pay me more than that — relative to the actual outcome, they could’ve paid me anything up to £16.66 and they would still have been better off.

So that’s it. In future, I will start demanding my friends pay me an attendance fee. It doesn’t have to be as much as £16, there’s clearly a negotiating space between that and the lower £3 figure. As with any business transaction, it’s my job to push it towards the higher number and theirs to keep it as low as possible.

On reflection, I’m starting to see why you shouldn’t invite economists over for dinner, and perhaps why I may not be invited in future…

More by this author