A sideways look at economics

How do you know someone has run a marathon? They will write a blog about it — twice, in my case. I made my way around Dublin last Sunday, committing the original sin of marathons of going out too fast in the first half and then ‘bonking’[1] by the end. Some, including Pheidippides, might argue that running even one marathon is the mistake. He is said to have died immediately after sprinting 26 miles to Athens to bring news of a victory in Marathon. (Pheidippides had reportedly run from Athens to Sparta and back in the three days prior, racking up an additional 300 miles. Tapering, it seems, is one thing that Ancient Greece didn’t invent.) I’m pleased to report that running has had a more positive impact on me than it did on him, clearing my head and providing valuable time to think. During a loop around the National Mall, it dawned on me that there may be lessons for economic policymakers.

Structural forces

Most people tend to focus on marathon day itself. As you locate a quiet spot along the route, compose a witty sign and cheer on your friend or family member, the race seems like the hardest part. In reality, the vast majority of the hard work has already happened in the weeks and months before. Diet, fartlek[2] and long runs. Effort and training over a longer period of time is what determines finishing times. Likewise, many people tend to focus on GDP per capita today, and discount the structural factors that helped to cause it: investment in human and physical capital over years and even decades; regulators with bite, who ensure competitive markets; and stable, predictable macroeconomic policymaking. Many of the decisions that drive living standards today were made long ago. Achieving a high-income economy is a marathon, not a sprint.

Overdoing it makes things worse

If you ask me, the desire for a new PB (personal best) is as universal as the desire for sustained, high economic growth. In my case, it caused me to complete the first 13.1 miles too fast, buoyed by a short-run thrill that discounted future risks. Likewise, a desire to boost economic growth has historically pushed policymakers towards excessive stimulus. The short-term rush feels good. Indeed, for a while, I felt faster than I was. With stimulus, people feel richer — for a bit. The feeling is fleeting. I crashed. And research shows that marathon world records have often been broken with slight negative splits, but with athletes running each mile at roughly the same speed.

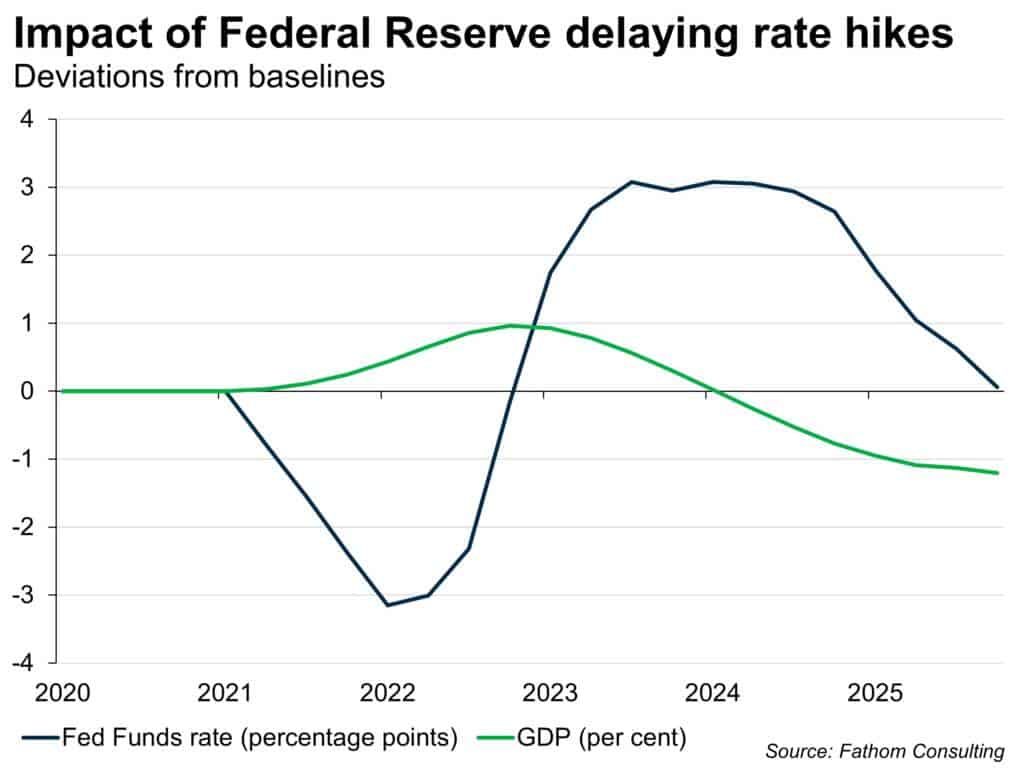

Something similar can be said about policy. Steady changes to policy are thought to achieve the best outcomes. The chart below shows a model simulation of how delaying rate hikes leads to higher policy rates and lower GDP than otherwise. Incidentally, it’s worth nothing that studies show men ‘consistently overestimate their abilities relative to women’ and ‘men slow more than women in the later stages of the race’.[3] They pin this on overconfidence. Assessing whether this finding is true for economic policymaking would be an interesting strand of research. The UK’s experience with Liz Truss suggests misplaced belief in one’s ability is not a uniquely male trait.

Luck isn’t everything

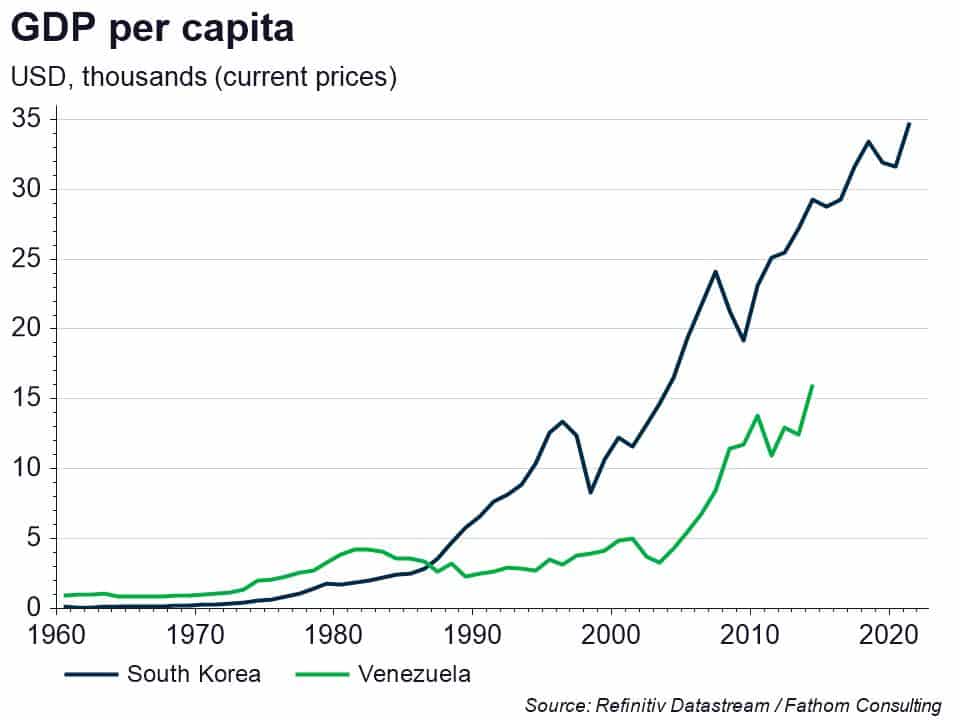

Luck is important but it’s not everything. Most long-distance runners hail from high altitude areas in east Africa. Having a body that is more accustomed to lower oxygen levels helps to drive efficiency. Looking at the long-term performance of economies, some countries are lucky enough to benefit from large stocks of valuable natural resources. But that isn’t the be all end all. South Korea lacks plentiful natural resources, while Venezuela has the world’s largest stock of oil reserves: yet South Korea has managed to increase its living standards by much more. Similarly, Ireland: formerly one of the poorest countries in Western Europe, it is now one of the richest (yes, even accounting for the impact of Apple’s dodgy tax affairs), thanks to investment in human capital and a cross-party consensus to make the country an attractive destination for FDI. The comparisons with running still hold: with the right training, almost anyone can run a marathon in a good time. Admittedly, you probably need to be gifted genetically to win the Olympics. I believe the same is true for a country’s living standards. Reaching the top worldwide involves luck, but there is no reason that currently low-income countries cannot raise their overall living standards materially with the right policymaking.

My form of stimulus led to cramp that was not transitory, and that resulted in a limp finish. Fortunately, five days on all soreness has gone. The looming global recession reflects (in part) excess stimulus a couple of years ago. Soreness from that may linger. But the lesson isn’t to be timid. An excessive caution – austerity in economics – also leads to subpar outcomes. There is a sweet spot where we push ourselves to the limit, but without leading to damage that does more harm than good. In my case, that means increasing my average speed and weekly mileage. For governments, that means stable policymaking and continued investment in infrastructure and R&D. The fruits from these changes may not be immediately obvious. In my case, I’m hoping to see positive results in the London marathon next April. Policymakers may have to wait longer than that, but that should not detract from the urgency of the task. Quite the opposite, in fact – the sooner they get on with it, the better.

More by this author:

A guide to substitution in a high inflation world

[1] A runners’ term for reaching a point of exhaustion where it seems impossible to take another step. (Not the more usual meaning.)

[2] A system of training for distance runners in which the terrain and pace are continually varied.

[3] https://content.iospress.com/articles/journal-of-sports-analytics/jsa0008