A sideways look at economics

Every spring, we wage war on our wardrobes, dig through drawers of tangled chargers, and maybe even feel virtuous about evicting a forgotten printer. It is a familiar ritual — a quiet act of self-renewal, part tidying up, part taking stock. And while our homes may get lighter, our systems rarely do. Economies, like attics and garages, are packed with things we no longer need: outdated subsidies, faltering industries, policies built for a different era. Some are too politically sensitive to touch. Others are simply forgotten — buried under layers of compromise and convenience. The result is a remarkable ability to hold on. And a growing cost for failing to move on.

But it’s not just policies and firms. Our mental attics are just as crammed. Outdated assumptions, legacy models and deeply ingrained habits linger well past their usefulness. Zombie firms shuffle along on policy life support. Investors stay loyal to structurally declining industries. Political narratives endure long after their relevance has faded. The cost of holding on is rising — and mostly unnoticed. In the spirit of the time old tradition of a ‘spring cleaning’, maybe it’s time we turned the broom outward. What does it really mean to let go — economically, institutionally, even culturally? And why are we so bad at it?

Our reluctance to let go isn’t a failure of logic — it’s human nature. Behavioural economists have shown that we are deeply influenced by the sunk cost fallacy: once we have invested time, money or emotion into something, we find it disproportionately difficult to abandon it (Thaler 1980). Loss aversion, another cognitive bias, makes losses loom larger than gains (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). We value what we own more than its market worth — the so-called endowment effect.

This isn’t just a personal quirk. Investors hold onto underperforming assets longer than they should, hoping to recoup losses rather than cutting their losses. Governments continue funding outdated infrastructure projects to justify prior expenditures. And firms refuse to pivot away from failing strategies because so much has already been spent building them. The outcome is a quiet but costly paralysis.

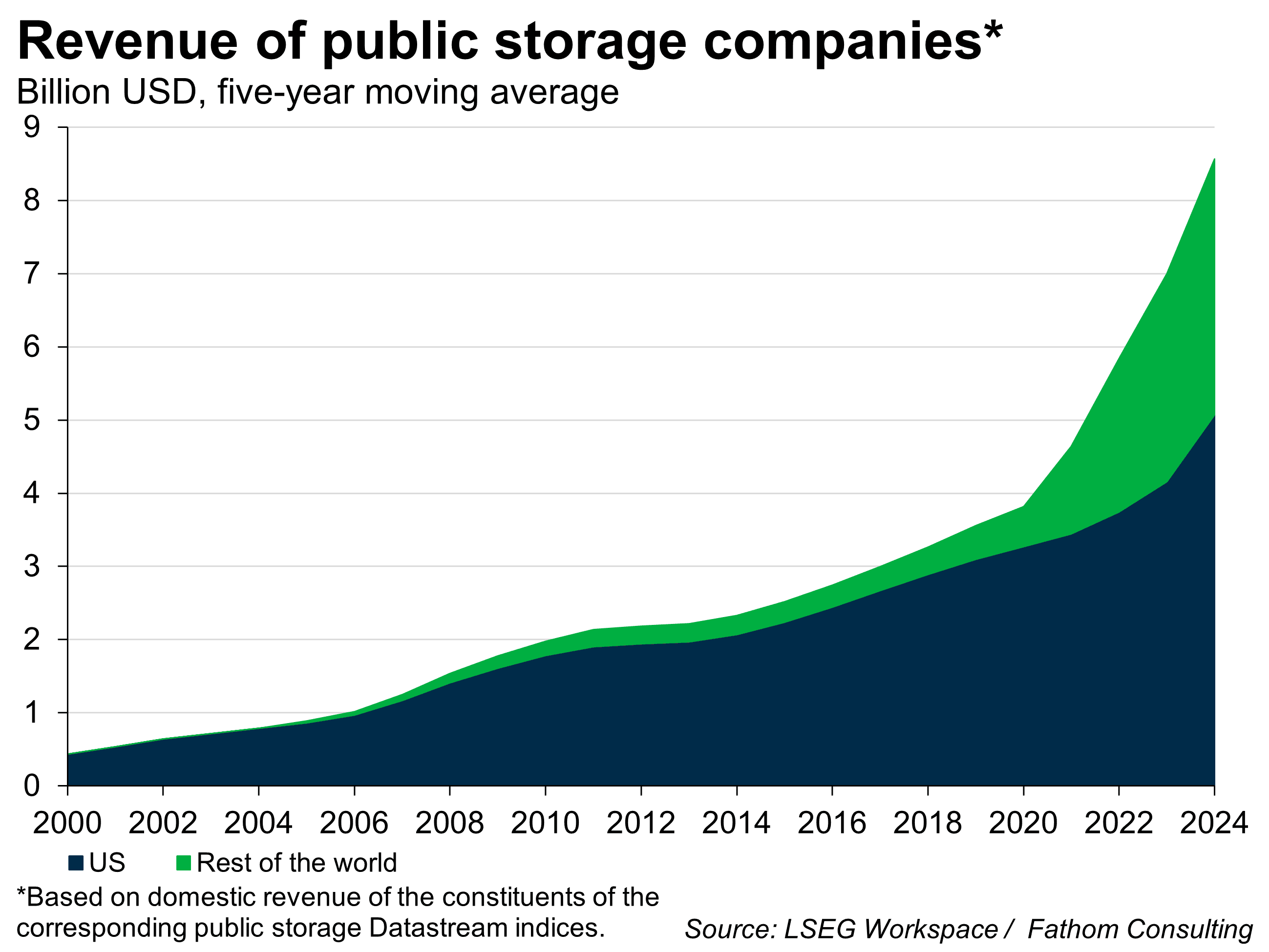

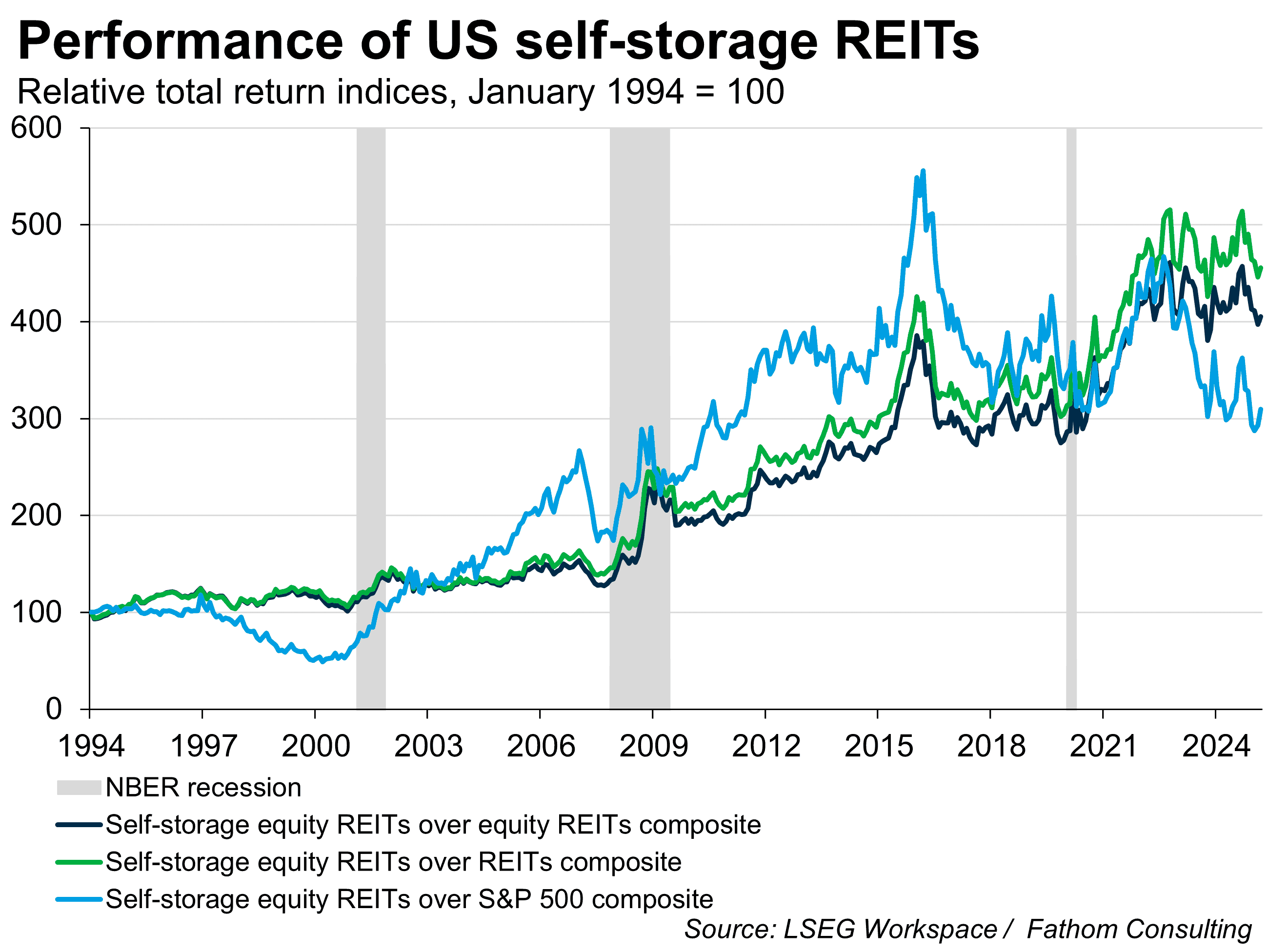

If our private spaces are cluttered, our economies are worse. One of the fastest-growing industries in the US over the past decade has been self-storage — a business largely built on our collective inability to let go. Americans now spend over $5 billion to store excess belongings with public storage companies, often things they no longer use but cannot quite bring themselves to discard. Globally, the figure rises by another $3.5 billion. If overaccumulation had a stock ticker, it might look like the self-storage real estate investment trusts (REITs), which since the end of Global Financial Crisis in 2009 have quietly become some of the most consistent outperformers — not only beating other REIT sectors but also not allowing the S&P 500 to overtake them, Magnificent Seven and all. In a market obsessed with innovation and disruption, it’s a striking reminder: sometimes, the best returns come from simply holding on — for better or worse.

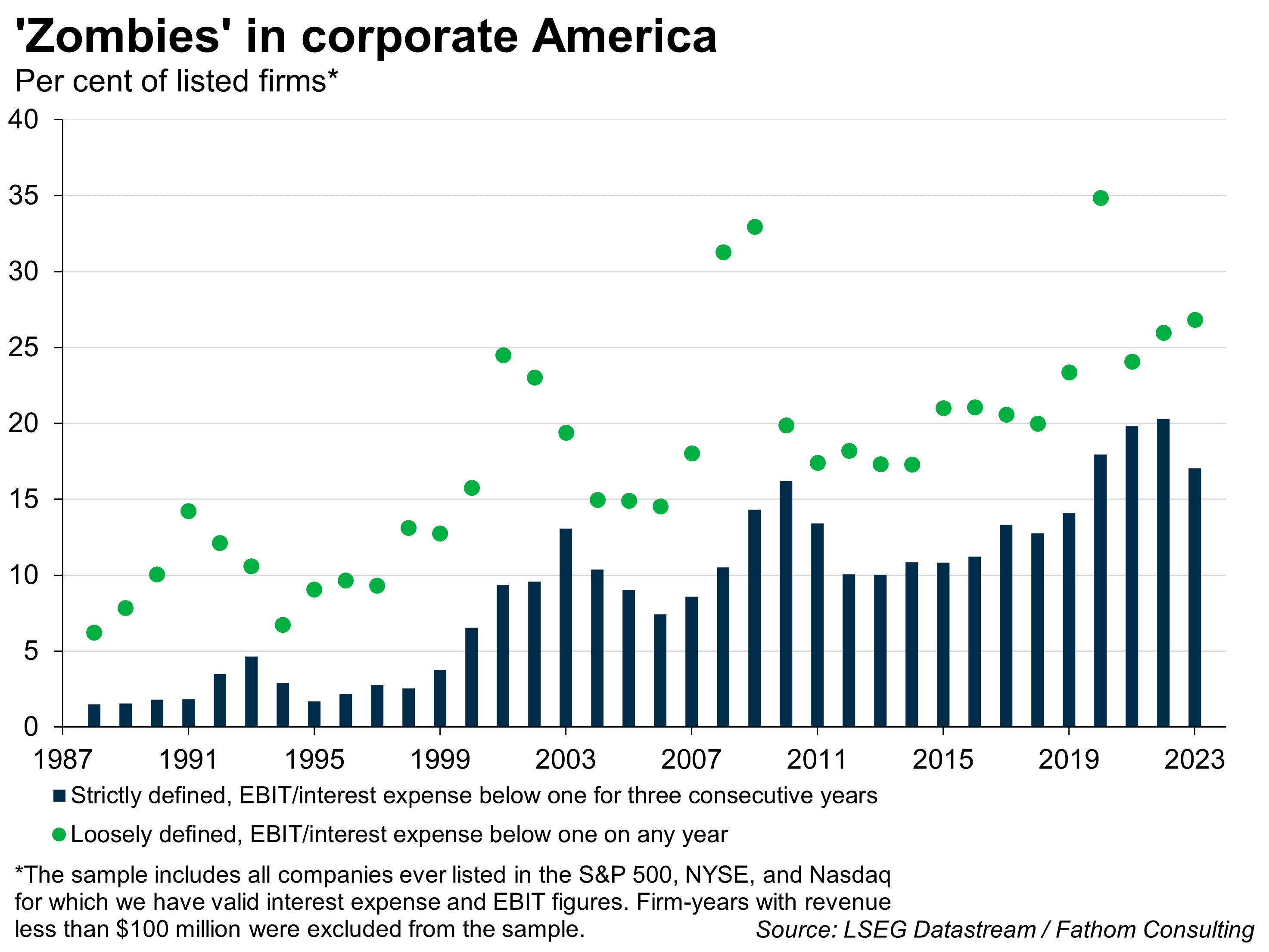

That same impulse — to preserve rather than release — runs through our economic systems. Just as we store unused items in rented units, advanced economies have increasingly sheltered underperforming companies. ‘Zombie firms’ — businesses that earn just enough to cover interest payments, but not enough to grow — have multiplied since the 2008 financial crisis. According to Fathom’s analysis, supported by the work of the Bank for International Settlements, the share of publicly listed zombie firms in the largest economy in the world has climbed from around 4% in the 1980s to over 15% by 2023 (or from 10% to 25% if you prefer the loose ‘zombie’ definition). These US firms tie up capital and labour that could be put to more productive use, yet they persist — sustained by cheap credit, institutional caution and a deep-rooted aversion to creative destruction.

Why do institutions and policymakers struggle to let go? Part of the answer lies in political risk: ending subsidies or shutting down failing firms creates visible losers, while the gains from reform are diffused and delayed. Cultural narratives also weigh heavily. The attachment to coal towns in the UK or manufacturing hubs in the US isn’t just economic — it’s identity-based. Meanwhile, regulatory and tax systems often hardwire inertia into the system. The US tax code, dense with loopholes and exemptions, reflects decades of political compromise few are willing to revisit. Many of these provisions act as hidden, regressive subsidies — politically untouchable, despite their inefficiencies. Similar dynamics play out in Europe, where the Common Agricultural Policy continues to channel billions to farmers with little environmental or structural reform. In Japan, employment protection reflects a legacy of lifetime jobs and rigid labour practices that resist modernisation. We like to imagine policy as forward-looking. In practice, it often serves to preserve the past — and the structures built to protect yesterday’s gains can become the very barriers to tomorrow’s progress.

Letting go has an image problem. We tend to see it as surrender — a reluctant waving of the white flag. But in truth, it’s a form of discipline: the willingness to accept that what worked yesterday may not serve us tomorrow. At its best, it’s a statement of confidence in the future. Consider Apple. In 2007, the iPod was still a cultural icon and a best-seller — the crown jewel of Apple’s product line. Yet even at its peak, Apple chose to cannibalise it by launching the iPhone. This wasn’t just a technological pivot; it was a strategic act of self-disruption — letting go of a beloved product in favour of one that would redefine both the company and the industry. That decision laid the groundwork for Apple to become the most valuable company in the world. Now contrast that with Kodak. Despite inventing the first digital camera in 1975, Kodak clung to its legacy film business, fearing that embracing digital would undercut its core revenue. Management saw the wave coming — and froze. By the time the company acted, it had lost both market share and momentum. What it couldn’t let go of ultimately cost it everything (see the details of the Apple and Kodak case study in Lucas and Goh 2009).

This tension plays out at every level. Germany’s Energiewende — more than an energy policy — represents a national commitment to structural transformation: a deliberate shift away from nuclear and fossil fuels toward a renewable-based energy system. Launched in the early 2000s, it has involved public investment, legislation, and massive infrastructure change — messy, controversial, and politically fraught, but grounded in a willingness to trade short-term comfort for long-term resilience. Letting go also happens more quietly: the factory worker who retrains for a digital job, the teacher who learns data skills, the journalist who picks up coding. These aren’t just acts of survival — they are reinventions. As David Autor (2019) has shown, those who embrace reskilling tend to fare better not just economically, but in adaptability and long-term well-being. Schumpeter called it “creative destruction” — the idea that progress depends on dismantling what no longer works. Letting go, in this light, is not loss. It’s preparation. It’s how we clear space for innovation, productivity, and whatever comes next.

Spring reminds us that renewal begins with release. The things we cling to — old policies, institutions, identities — can quietly become constraints. Left unexamined, they block progress. Economies, like wardrobes, benefit from the occasional clear-out. Perhaps the real invisible hand isn’t guiding markets, but gently prying our fingers off the past. And maybe, in the quiet of a freshly cleaned room or a sunlit policy rethink, we discover that letting go isn’t a loss at all — just a different kind of growth.

More by this author