A sideways look at economics

Irish voters head for the polls today with housing the dominant issue. High prices are widely seen as a key factor driving disenchantment among young people. The festive season is beginning, so forgive my adding to that disenchantment with what I’m about to say. But decisions taken in foreign capitals and boardrooms may have far greater consequences for Ireland’s economic luck in the coming years than any domestic plebiscite.

Why? Because Ireland’s low effective rate of corporate tax has made the country a magnet for very large corporates. The presence of these huge companies has distorted Ireland’s national accounts data in lots of ways. To give one example, a recent ruling forced just one large US multinational (Apple) to pay the Irish government €13 billion ($14 billion) in back taxes. Scaled for differences in Irish and US GDP, the ruling would be the equivalent of Apple being ordered to pay the IRS $700 billion in back taxes. Not a bad gig if you can get it.

That same corporate tax rate is now making a mockery of Ireland’s official fiscal figures. Apple’s annual revenue totals more than half of Ireland’s GDP (it probably artificially boosts it by significant sum, too), and so its tax bill can have a huge impact on government receipts. With many governments facing the dual headwinds of lingering pandemic debt and high interest rates, Ireland finds itself flush, recently looking beyond a self-imposed 5% limit on the annual growth in government expenditure with an announcement that spending would increase by almost double that amount.

Corporate tax receipts in Ireland have risen from under €5 billion in 2014 to a forecast of almost €40 billion in 2024. At more than a third of total government revenue, they are expected to rise above income taxes in cash terms in the short term. That marks a stark contrast with the average OECD economy, where corporate taxes tend to account for just 10% of total revenue raised. Ireland’s tax base is so concentrated that just three companies paid 43% of all corporate tax receipts in 2022. But the scale of these sums carries with risks, as any changes to the global tax regime, or even to the executive committee of a large multinational, could have profound effects on Ireland’s fiscal outlook.

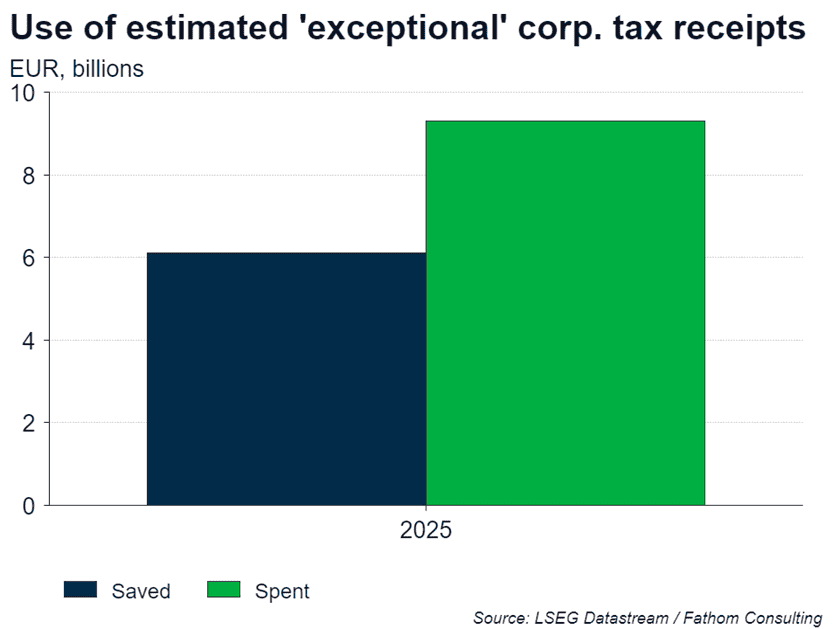

Faced with what seems to be a temporary increase in income, what should the government do? A lesson from Milton Friedman is to respond to one-off changes in income by saving it. Amid uncertainty, governments may opt for a so-called ‘bird-in-hand’ approach, where it only spends the gains earned on historical savings. The overall theory makes sense, but the specifics are challenging. Nobody knows just how long Ireland’s corporate tax windfalls will continue. For now, however, the government is prioritising ‘jam today’. In the most recent Budget, 60% of estimated ‘exceptional’ corporate taxes were spent on pre-election giveaways, with just 40% put into two newly created sovereign wealth funds.

Will this approach to the Budget turn out to be overly austere or overly generous? My suspicion is the latter, and given the country’s recent history of boom and bust, it would have been wiser to focus on building up assets for a rainy day. Whoever becomes the new Taoiseach would be wise to begin planning a US charm offensive immediately. From Ireland’s perspective, it will be critical to ensure that any changes Mr Trump makes to the US corporate tax code do not eliminate Ireland’s ‘exceptional’ corporate tax gains as well. If Ireland’s new leader succeeds in pulling this off, they’ll likely find themselves in good stead come the next-but-one election. Thinking of the country more broadly, perhaps we’d need to stop calling these windfalls ‘luck’. Coming up with a strategy to disproportionately shift global corporate ‘activity’ to your low-tax economy? Easy. Getting away with it year after year? That takes skill.[1]

[1]Lowering corporate taxes is politically toxic (even right-wing candidates struggle), despite a rate as low as zero having theoretical foundations. Ireland accounts for 0.8% of OECD GDP but gets 1.6% of corporate taxes.

More from Thank Fathom it’s Friday