A sideways look at economics

I have just returned from ten days in Gozo, an island off Malta, the supposed location of Calypso’s cave, in which Odysseus was imprisoned for seven long years on his journey home from Troy all that time ago. The island is small – you could drive the perimeter, if there were no traffic, in perhaps 45 minutes. There is no city, but a string of small towns and villages that have spread over time and now mostly run into one another without interruption. The buildings are made of the local sandstone, and are an attractive honey colour as a result. Some are very old, hundreds of years old in some cases, maybe more. But none is as old as the megalithic structure in the middle called Ġgantija, said to pre-date the pyramids and Stonehenge.

This structure has been subjected to many depredations over the last five thousand years: farmers clearing stones to make way for crops; builders recycling the stones into houses or walls; visitors gathering souvenirs and etching their names into the larger stones that remain; archaeologists rebuilding what they believed to be the original structure, adding to or renovating the stones where they felt that necessary; and so on, generation after generation. It is unclear how closely the current structure resembles the original, though there are some elements that are probably intact even over that enormous span of time. Standing in the remains, you command views all around the island, to the cliff edges on all sides.

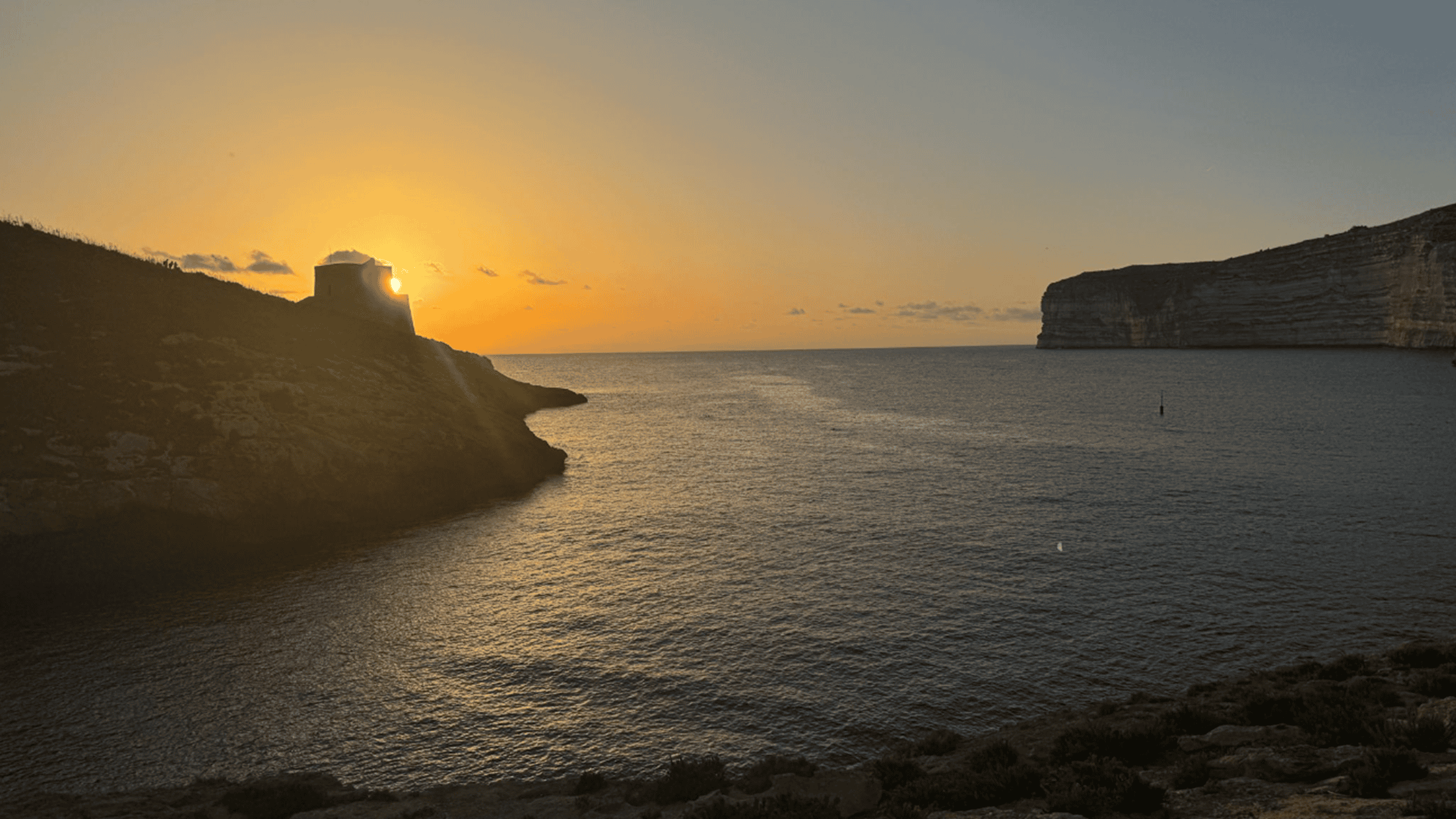

Gozo’s topography is very striking, with tall, striated sandstone cliffs tumbling into the sparkling Mediterranean, punctuated by a handful of narrow inlets that create natural harbours. It is extremely hot in the summer, and the terraced fields were still largely dry, dusty and brown when we were there. The climate has changed noticeably in the last ten years, according to residents: summers have become hotter and drier, and water more scarce the year round.

To walk to the cliff edges from one of the villages, you must negotiate narrow alleyways that give onto crumbling stone paths. Along the way, you will hear the chirping of caged birds and the irregular ‘tac-tac’ of guns. Some of the Gozitan population are obsessed with trapping and shooting birds. They trap small birds and breed them in cages on their roofs. And they use those small birds as bait to attract larger, predatory species, which they then shoot, for reasons best known to themselves: I assume there is money involved. The shooting ranges are littered across the hillside around the cliff edges, and are poorly delineated. So, stumbling up to the cliff path you might find yourself (as we did) stumbling into the shooting range of a large, burly chap ensconced in a low stone hide, who emerges shouting and waving his hands, encouraging you (in no uncertain terms) to stick to the path.

These stone hides appear everywhere. Apparently, the Maltese have a derogation from the EU that permits the shooting of otherwise protected species of birds, for ‘cultural’ reasons.

But the hides are not the only stone buildings going up. Everywhere, in every town and village, there is a forest of cranes. The old stone buildings are being demolished and replaced with new stone buildings, apparently designed to house tourists. For the same reason, existing buildings are being extended upwards and outwards. Empty lots are being filled. And undeveloped land is being developed.

Tourists come to Gozo in large numbers, attracted by its unusual topography and its relatively undeveloped condition, compared to the main island of Malta. Apparently, ten years ago and more, there was a plan to turn Gozo into an ‘eco’ island, protecting both the flora and fauna, encouraging sustainable development of both. That model of development for a small island makes a great deal of sense to me. But it is obviously incompatible with massive construction activity, including the demolition of existing buildings of historic interest. And it is inconsistent with mass tourism too: it is hard to see how the flora and fauna could survive increasing inflows of tourism. Finally, it is inconsistent with a policy of shooting species of bird that are protected elsewhere.

The revealed preference of the authorities in Gozo, as in many other small islands, is a race to the bottom, chasing cheap mass tourism rather than selective, high-end tourism. For the former, you need loads of houses and reliable sun. For the latter, you need a beautiful environment and interesting flora and fauna.

The mass tourism route is deadly for the long-term prosperity of small islands. Every marginal increase in tourist numbers will damage the environment still further, bidding down the revenues the island can accrue from each tourist and necessitating a further increase in the number of tourists. It’s a one-way route to environmental and economic disaster. But it makes a quick buck for those involved in construction activity along the way. This process is already underway, as noted in a recent article in Malta Business Weekly that surveyed local tourist businesses:

“Notwithstanding the fact that inbound tourist arrivals increased by 21% during the first five months of 2024 … tourism operators in Gozo encountered [a] decrease in their revenue during the first half of 2024, compared to the same period of 2023.…Finally, an alarming 85% of respondents believe that the general touristic offer in Gozo is not meeting guests’ expectations due to various factors including excessive construction, lack of tranquillity, poor infrastructure, noise disturbances, and cleanliness issues.”

I would add to that list a concern that the natural flora and fauna are not being adequately supported. Tourism in Gozo, as it is currently structured, is creating a self-reinforcing feedback loop leading to worse and worse outcomes. I am one of those tourists: I have played my part. I feel happy to have seen Gozo, as it is beautiful and interesting. But I feel sad to have contributed, however marginally, to its decline.

Odysseus was another tourist, in a way (though there was no such concept then). In the story, Calypso loved Odysseus the ‘tourist’: in fact, she loved him too much. Her love was not reciprocated. The Gozitan authorities now are repeating her mistake.

If there ever was such a person as Odysseus, and if he ever visited Gozo, that character from one of the oldest surviving stories our species has in its possession would have found Ġgantija already there, already ancient, already much changed from its original form. And, of course, the island itself was there for millions of years before Ġgantija was built. The island will survive its current depredations, though it will be changed by them, as its talismanic monument has been. Nevertheless, I wish we could find a way to treat it, and other small islands, better. Gozo should be paradise; it isn’t, because of us.

More by this author