A sideways look at economics

Given recent passionate debates by colleagues Erik and Elisabeth about economic models and ’rational man‘ — homo economicus — how could I pass up this opportunity, on Friday the 13th, to write about empirical economic evidence for superstitions?

Friggatriskaidekaphobia, or the fear of Friday the 13th, has proved to be a persistent Western superstition, rooted in Christianity and Norse mythology.[1]

Christians believe that Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus Christ of Nazareth, was the 13th guest at the Last Supper, which took place the Thursday night before the crucifixion. Similarly, the Norse god of mischief, Loki, was the 13th, uninvited guest at a dinner party of the gods in Valhalla, where he commissioned the murder of the god Balder, plunging the world into darkness.[2]

But as economists, why should we care about these deep-rooted cultural and spiritual beliefs about Friday the 13th, or any other superstitions for that matter? Typically, as an economist, I would say: “well, it depends”.

The economic value of superstitions

Whether from the orthodox or heterodox tradition of economics, it’s impossible to deny that superstitions can affect human behaviour and, in turn, affect the allocation of economic resources according to the Journal of Economic Psychology.[3] However, the journal wrestles with a paradox niggling at us economists: “If people are rational, it is puzzling why superstitions persist”. Using evidence of risk-aversion on Fridays alongside a game-theoretic model with rational learning, superstitions as beliefs about events are taken off the equilibrium path and characterise the conditions under which a false belief can persist. Two important implications follow from this research: first — under the rationality assumption, some superstitions can persist; and second — in equilibrium, persistent superstitions in turn do affect the behaviour of people.

The first assumption, that rationality and superstition can exist side-by-side depends on the nature of the superstition. Many superstitions are rooted more in commonsense than in folklore – such as opening umbrellas inside or breaking mirrors, both hazardous. Take walking under ladders, which several of my (seemingly rational) colleagues at Fathom tell me they would not do. Some point out it is a practical health and safety concern – where there are ladders there are likely to be workmen overhead. As for the practice being potentially unlucky, some shrugged: “why take the extra risk [of bad luck] when you can easily walk around it?”

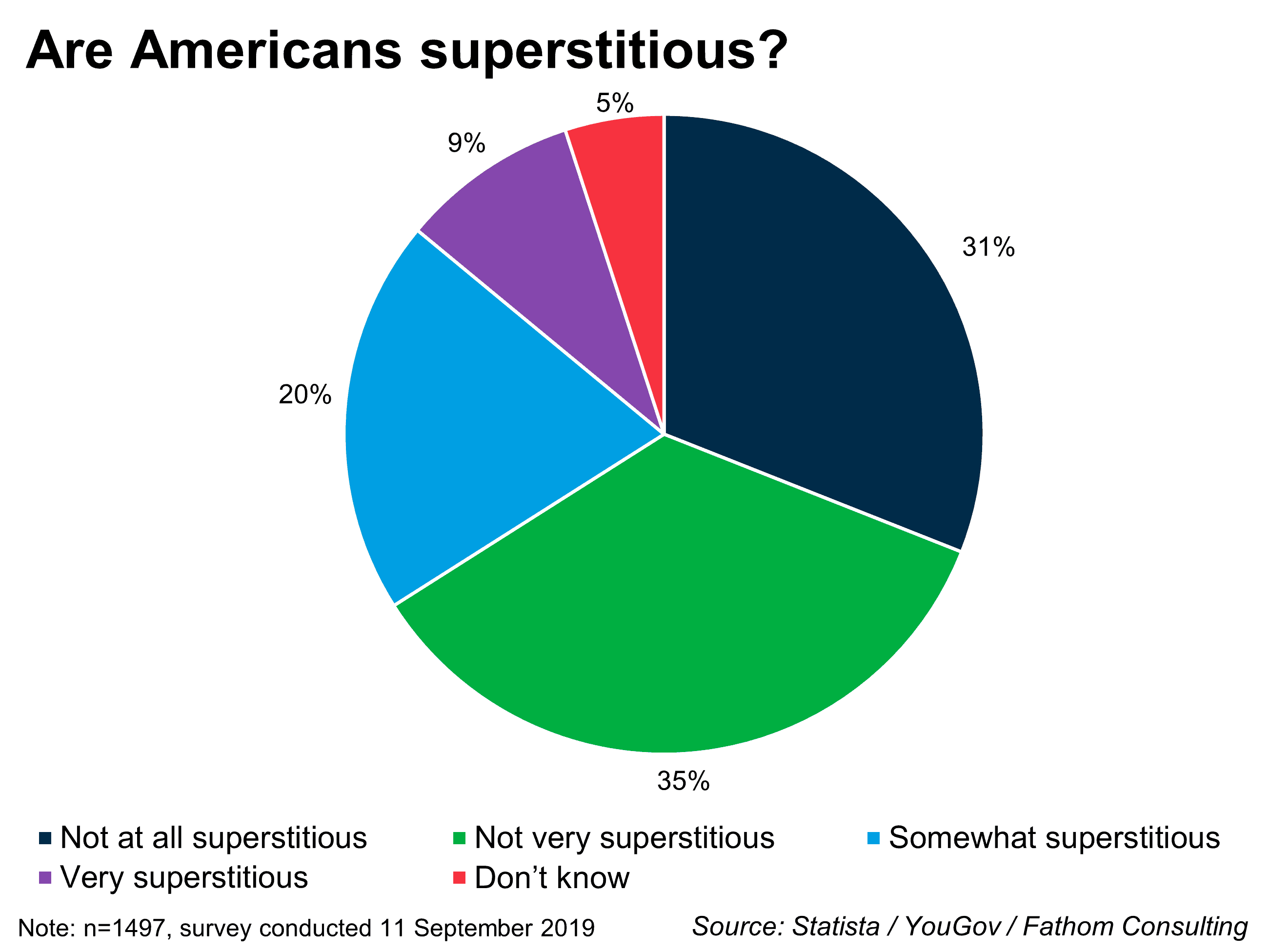

I guess this kind of seemingly rational arbitrage reveals that most people, including economists, are secretly more superstitious than they would like to admit.

But what is the idea of ‘luck’ really? It is believing that the negative/positive outcome of any event is brought about by chance, or some other force other than your own actions. Superstitions double down on this with the belief that supernatural influences, especially moonlight, sigils, magic rituals or lucky charms can guarantee a particular outcome. Yet, here we are, in the 21st Century, with our technological and scientific progress, seeing a resurgent witchcraft and new-ageism embraced by ‘Gen-Z’ under the guise of ‘self-care’ as an alternative to political, religious and economic systems that have not delivered.[4][5] This has led to the resilience of seemingly irrational superstitions and other magical beliefs drawing debate about their significance for observed phenomena, economic or otherwise.

On the one hand, could it be that the horror show of our politics has elicited a shift from patriarchy/authoritarianism and towards witchiness/decentralisation? On the other hand, could it be that science itself has delivered magical objects that Gen-Z has grown up with? If we could teleport an average Celtic Druid to 2024 here to the peak of the Anthropocene epoch, with its smartphones, electricity and airplanes, they would undoubtedly see our world as filled with magic.

Source: Microsoft Copilot / Fathom Consulting

Magic vs religion and science

The idea of magic has always existed in opposition to as well as in parallel to religion and science as a fundamental pillar of knowledge. In a recent book on the history of magic, the archaeologist Chris Gosden [6] explains how magic evolved as one of the great strands of practice and belief throughout human history, in all cultures and continents. Magic, says Gosden is, for human beings, the way in which we have explored our connection to the universe and power to act on the world. Yet it has developed a bad reputation, despite having been with us for millennia, and notwithstanding its profound influence on scientific ideas.

Science evolved directly from magic: the roots of chemistry are in alchemy; the logic of mathematics is anchored in mysticism; and metaphysics underpins enquiry in quantum physics. Ergo, the formal study of economics evolved from the philosophy of The Enlightenment.

A key difference between science and magic of course is that one is meant to be explainable, and the other is essentially an act of faith. A small overlap may exist, however, and what could not be explained and deemed magical at first could find a scientific explanation later on. In extending the metaphor further, it could be said that there are many false positives (Type 2 errors) in magic.

Philosophy, religion and science also have malleable boundaries depending on the hegemonic ideology. For example, the economist Benno Torgler in his research on determinants of superstition found that “people from formerly Communist countries show a particularly high degree of superstition [because] superstition substituted the religious beliefs and activities eradicated during the Communist era,”.[7] Similarly, the supremacy of STEM subjects following The Enlightenment displaced belief in God and the authority of the church with an accompanying disdain for the humanities. Nonetheless, as Gen-Z has shown, magic remains a core branch of human belief systems, alongside science and religion, in relation to the ways in which the world can be understood and, as such, superstition with all its lucky charms and rituals will never disappear. So, with all that covered off, the question begs: how pervasive is the idea of magical thinking in economics? Well, it depends.

Rational expectations as magical thinking

A centrepiece of economic rationality is found in asset-pricing theory, particularly in the so-called Rational Expectations Hypothesis (REH), which presumes that economists can model exactly how rational individuals comprehend the future. Alec Balasescu and Apurv Jani[8] assert that REH itself is a form of magical thinking because it supposes that each of the many models devised by economists provides the ‘true’ account of how market outcomes, such as asset prices, will unfold over time. They say:

The Asset must also provide the promise of a better future through a simple action. If this sounds like magic, it is because it is magic by the book. It describes a combination of beliefs and actions backed by rituals meant to reduce uncertainty in situations of risk.

The ‘thought experiment’ presented by Balasescu and Jain is extremely useful in demonstrating how the empirical supremacy of so-called ‘rational’ systems of knowledge, like economics, rely on similar mental toolkits to more ‘irrational’ systems like magical thinking. On the other hand, an economist devil’s advocate might contend that the point of the strength of the REH is precisely that it is false (it is an assumption after all), and yet it does not invalidate certain types of economic outcomes and equilibria that can be falsified in spite of the assumption.

Investing and magical thinking

In orthodox economic theory, where the REH holds, investors are meant to be rational actors with rational expectations. However, in behavioural economics, human irrationality and bias are factored into expectations around asset prices. The theory of manias, panics and crashes, as explored by Kindleberger and Minsky, is a useful lens through which to explore expectations as magical thinking in investing.

The behaviouralists[9] feel that the rational school of economics doesn’t recognise the irrational ‘humanness’ of humans, whereas proponents of the rational school, such as Eugene Fama, contend that behavioural economics and finance lacks structure and opportunistically interprets random events with expedient anecdotes. “Neither of these schools make endogeneity a central feature of the system”, say Balalescu and Jani. On the other hand, the explanations based on endogeneity, such as the ones offered by Minsky and Kindleberger almost eliminate individual human behaviour. Here, anthropological concepts such as myth, ritual and magic become useful tools for seeing the financial market as a structure that explains and reflects human behaviour. This also bakes in the tendency of human beings towards narrative thinking when attempting to explain phenomena. And narrative thinking is the ur-magic, since it ideates the self-fulfilling prophecies that manifest beliefs. Asset prices consequently either soar on euphoric market streaks or decelerate at speed in debilitating bank runs and market crashes.

The Financial Times recently interviewed Eugene Fama, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), which purports that stock market prices at any time incorporate all available information and as such reflects the rational expectations of market actors. The FT’s Robin Wigglesworth therefore describes the EMH as the closest finance has to a “theory of everything”.

In this interview, Fama also says the efficient market hypothesis is just “a model … it’s got to be wrong to some extent. The question is whether it is efficient for your purpose. And for almost every investor I know, the answer to that is yes. They’re not going to be able to beat the market so they might as well behave as if the prices are right”.[10]

Fama here indicates that these two schools of thought may not, in fact, be as bifurcated as they first appear, in encouraging us to see EMH as a thought experiment. Moreover, could it be that the market may be efficient precisely because everyone is trying to beat it? If none tried there would be substantial arbitrage opportunities that would entice new entrants and make it efficient again.

Stock prices and Friday the 13th: the empirical evidence

Investors are notoriously superstitious and in addition to their beliefs about stockpicking on Friday the 13th, they also believe that investing on a full moon can hex their portfolios.

I like to think about this kind of behavioural irrationality in investing as an economic ‘friction’ destroying efficiency maximisation, alongside regulation and market manipulation.

One fascinating origin story for Friday the 13th anxiety in stock markets, is actually about market manipulation. A novel published in 1907 by TW Lawson, titled, erm, Friday, the Thirteenth,[11] entrenched the belief. In the plot, an unscrupulous broker takes advantage of the superstition to create a Wall Street panic on a Friday the 13th. Lawson wrote prodigiously on the issue of market manipulation, and his exposés of stock-promotion and insurance practices helped bring government regulation into financial services. Lawson leaned heavily into the popular panic literature about investing at the time and was also the author of Frenzied Finance.[12]

Today, there is a whole literature on Friday the 13th as well as on stock return effects of other days of the week, or times of year. For example, ‘the January effect’ is the tendency for increases in stock prices during the beginning of the year, because of factors such as consumer sentiment and year-end bonuses. “The October effect” presupposes a greater likelihood of financial market crashes.

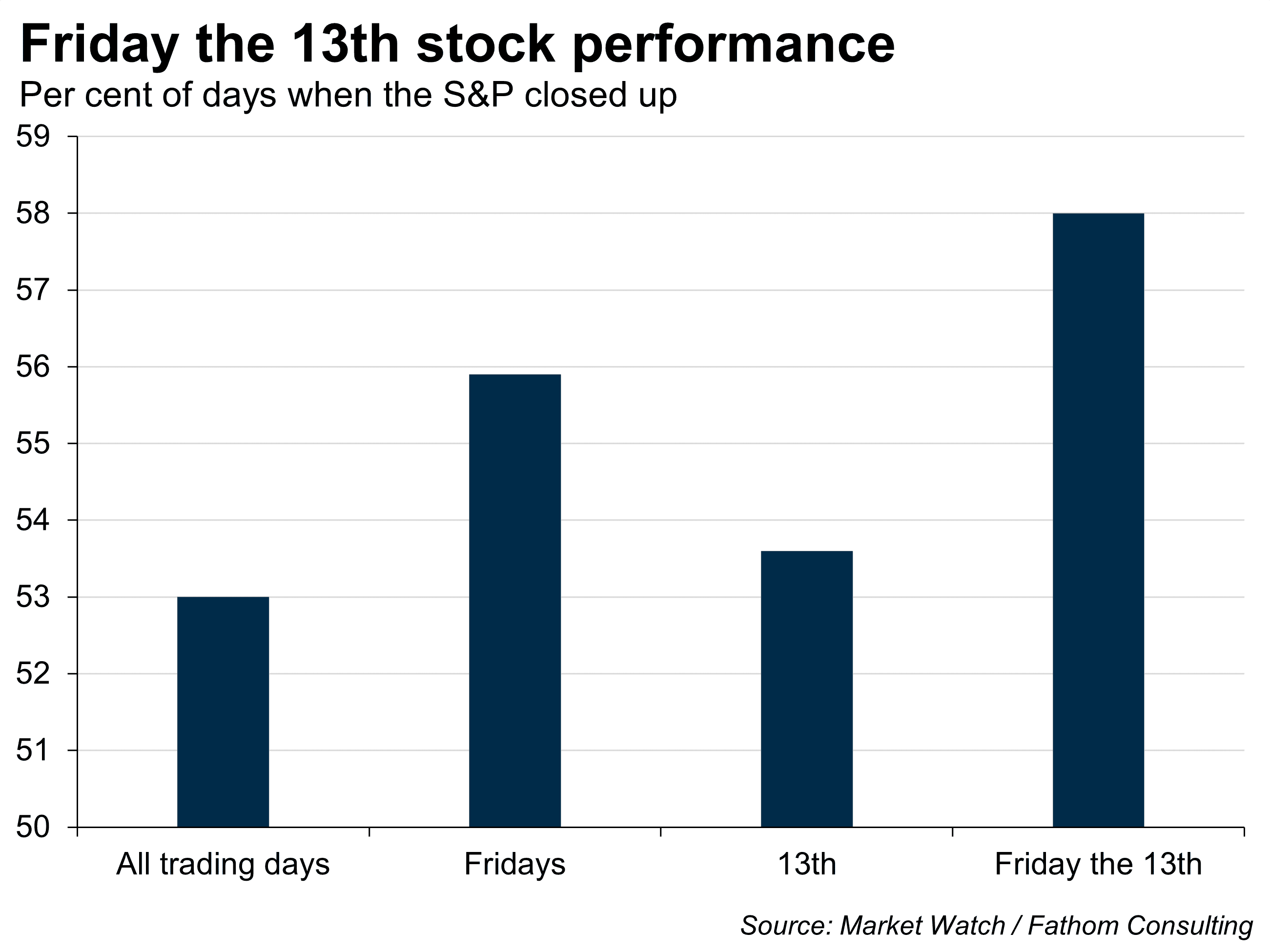

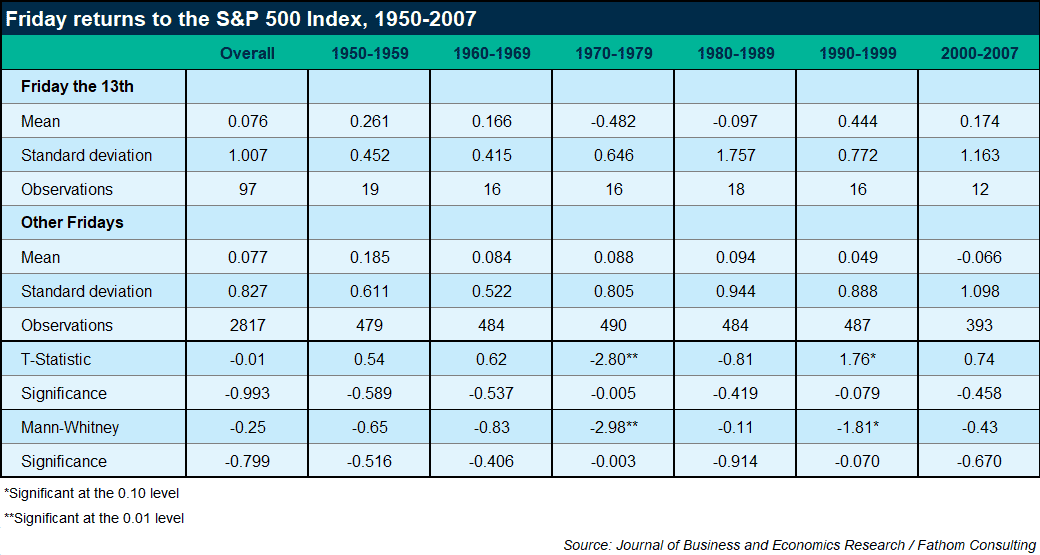

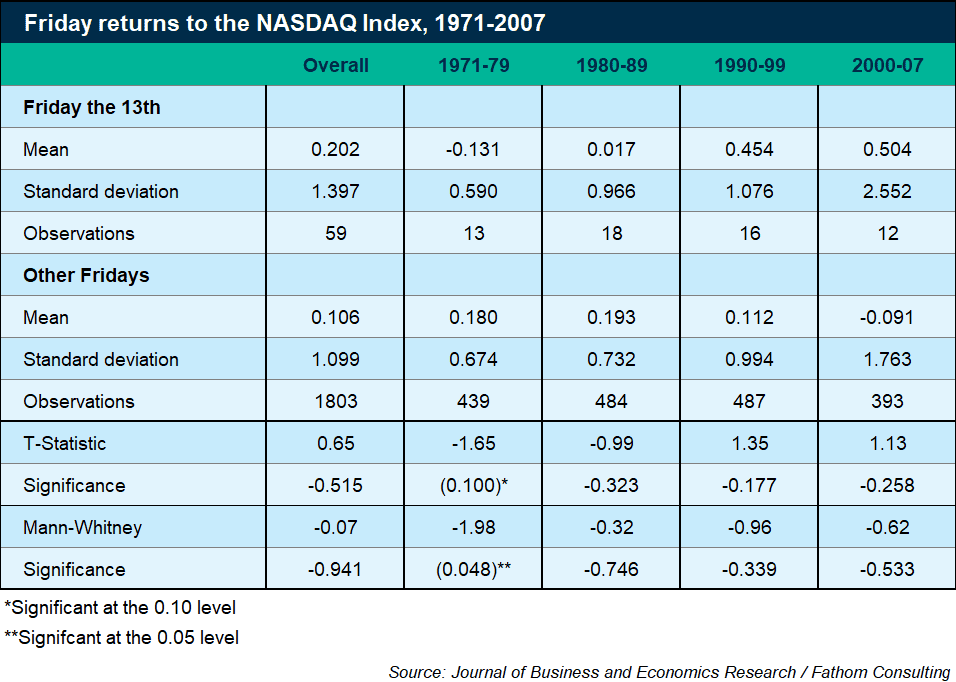

One particular seminal paper, in the Friday the 13th literature genre, is by Kolb and Rodriguez (1987),[13] has mixed results. On one hand, it shows that value-weighted index returns have been negative for Friday the 13th, on the other, it acknowledges that day-of-the-week literature often reports a positive, and unusually large, mean return for Fridays. A later paper by Prof Jayen Patel in (2009) re-examined Friday the thirteenth effect in the S&P 500 index and the NASDAQ index, which included more recent time periods and is more useful. The outputs are shown in the tables below.

Patel’s results are consistent with “earlier findings that the Friday the thirteenth effect was only documented in the 70’s and moreover, that most of the Friday the thirteenth literature finds that returns are actually higher than that of other Fridays in recent years”. It also reinforces the conclusion of Dyl and Maberly (1988) and Chamberlain, Cheung and Kwan (1991) that the US stock market does not demonstrate the Friday the thirteenth effect.[14] So is Friday 13th really more unlucky for investors? Well, the theory and evidence show that it depends.

[1] However, in Asia, , 4 is the unluckiest day, where the pronunciation of the word ‘four’ sounds the same as the word for ‘death’ in both Chinese and Japanese. While the number 13 could be considered unlucky tangentially and numerologically in Asia by adding 1+3 = 4, triskaidekaphobia is a relatively new import from Western culture, particularly in Japan.

[2] Incidentally, Fridays are also the day of Norse goddess Frigg, the mother of Balder.

[3] Ng, Travis, Terence Chonga and Xin Du. (2010) “The Value of Superstitions,” Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(3): 293-309.

[4] See: ‘The witchcraft generation: Gen Z is swapping traditional faiths for magic’ spellshttps://www.newstatesman.com/politics/religion/2023/08/strongfaith-faithless-age-strong.

[5] See also: ‘Generation Manifestation’: https://www.thinkhousehq.com/the-youth-lab/generation-manifestation

[6] ‘The History of Magic’ 2021 Chris Gosden https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/303993/the-history-of-magic-by-gosden-chris/9780241979662

[7] Torgler, Benno. (2007) ‘Determinants of Superstition’ The Journal of Socio-Economics 36 (713–733) https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1053535707000315

[8] Balasescu, Alexandru (Alec) and Jani, Apurv (2018) ‘Financial bubbles and their magic: asset price as a heroic journey in the financial markets’ The Journal of Philosophical Economics: Reflections on Economic and Social Issues. Volume XII Issue 1 Autumn 2018 (1-35)

[9] See Balasescu and Jain, 2018.

[10] Economist Eugene Fama: ‘Efficient markets is a hypothesis. It’s not reality’: https://www.ft.com/content/ec06fe06-6150-4f39-8175-37b9b61a5520

[11] This is really true. And you can read the whole sorry tale of Friday, the Thirteenth here on Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12345/12345-h/12345-h.htm

[12] You can see where I am going with this, and you can also read Frenzied Finance free of charge on Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/26330/26330-h/26330-h.htm

[13] Kolb, Robert W. and Rodriguez, Ricardo J. (1987) “Friday the Thirteenth: Part VII – A Note,” The Journal of Finance, Volume XLII, Number 5 (1385-1387), December 1987.

[14] Patel, J. (2009), ‘Recent Evidence on Friday the Thirteenth Effect in U.S. Stock Returns’. Journal of Business and Economics Research, 7 (3), 55-58.

More from Thank Fathom It’s Friday