A sideways look at economics

I enjoyed reading my colleague Elisabeth’s blog post, published last Friday, in which she quotes the former Norwegian Prime Minster, Gro Harlem Brundtland, who once declared: “It’s typically Norwegian to be good”. This got me thinking: what are we Brits good at? Many things, I hear you cry. To which I would specifically add: winning Olympic medals.

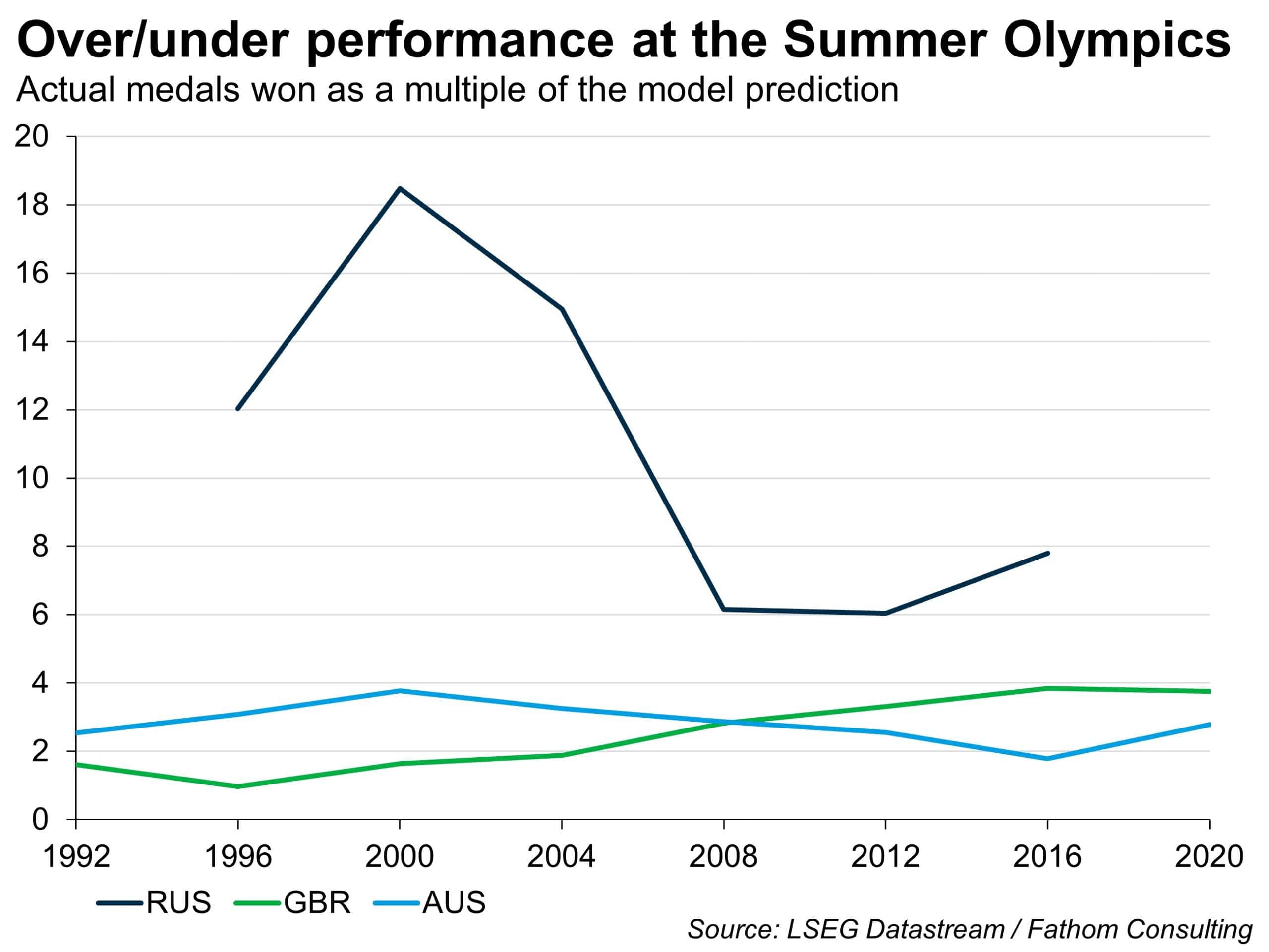

I am reminded of one of the first Thank Fathom It’s Friday blog posts that I wrote back in 2016, which tried to model a country’s success or otherwise at the Summer Olympics. At the time I was more interested in the unexplained part of the number of medals won – the part that appeared unrelated either to population size, or to the country’s economic resources. Who, in other words, was punching above their weight? I have now updated, and improved my model, and can report that Team GB does indeed outperform expectations, and has done so to an increasing degree over the past two decades. But in this respect, we are as nothing compared to the Russian Federation.

For this update (and who knows, it could become a quadrennial event), I have significantly expanded my dataset to consider each summer Games since the XV Olympiad, held in Helsinki in 1952. I have, in principle, included all 198 countries that have submitted a team since 1952, although 102 of those 198 countries are yet to win a medal. As before, I model the share of the total medals won by each country at each Olympiad as a function of its share of the global population, and its GDP per capita relative to the average for the world as a whole. This time I also allow for home advantage. All three explanatory variables are strongly statistically significant, with home advantage appearing almost to double the number of medals that we would expect the host nation to win.[1]

The model is not great. This is just another way of saying that it is hard to predict how well a country will perform simply as a consequence of the size of its pool of raw talent – its population in other words – and its economic resources. There are doubtless many other drivers of success that we have not accounted for. As before, I am interested in the residuals. I am interested in the countries that, for one reason or another, perform unexpectedly well (or, indeed, unexpectedly poorly). As my chart shows, Team GB has started to punch above its weight. At the XXXII Olympiad, held in Tokyo in 2020, it won an impressive 64 medals, close to 4 times as many as one might have expected, given its population and its economic resources. Impressive indeed and, importantly, better than the outperformance of our great sporting rival, Australia, which began to wane around the turn of the century.

But the outperformance of Team GB is as nothing compared with that of the Russian Federation. On average since 1996, when Russia first fielded a team of athletes under its own flag, Russia has won more than ten times as many medals as one might have expected. If we rank all countries according to their degree of outperformance, Russia leads the way. The countries in second and third place are also either current or former communist states, so it’s entirely possible that communist nations channel additional funds into training their athletes, over and above what one might expect given their economic resources. However, the fact that, amid allegations of widespread doping, the Russian Federation has been banned from entering a team under its own flag since the XXIII Winter Olympic Games of 2018 hints at another explanation!

So what can we expect from the XXXIII Olympiad, due to be held in Paris through July and August? Well, we trust that Team GB will continue to outperform our model prediction, after its degree of outperformance stalled during the COVID-affected Tokyo games, improving on its already impressive tally of 64 last time. And France, as host nation, could do very well indeed, raising its medal count from 33 to anywhere between 40 and 77.

[1] The home advantage variable is also statistically significant, but with a large range of possible values, suggesting some hosts are better able to capitalise on home advantage than others.

More by this author

Teaching the government how to budget