A sideways look at economics

It’s that time of the year again, the time to make New Year’s resolutions. Social media are full of marketing campaigns along the lines of “new year, new me”, and they seem to be working – 18 out of the 20 busiest days at the gym in 2022 and 2023 were in January and February, according to one study.[1] Let’s take a closer look at these New Year’s resolutions, whether they succeed in changing our behaviour, and their effects on the economy.

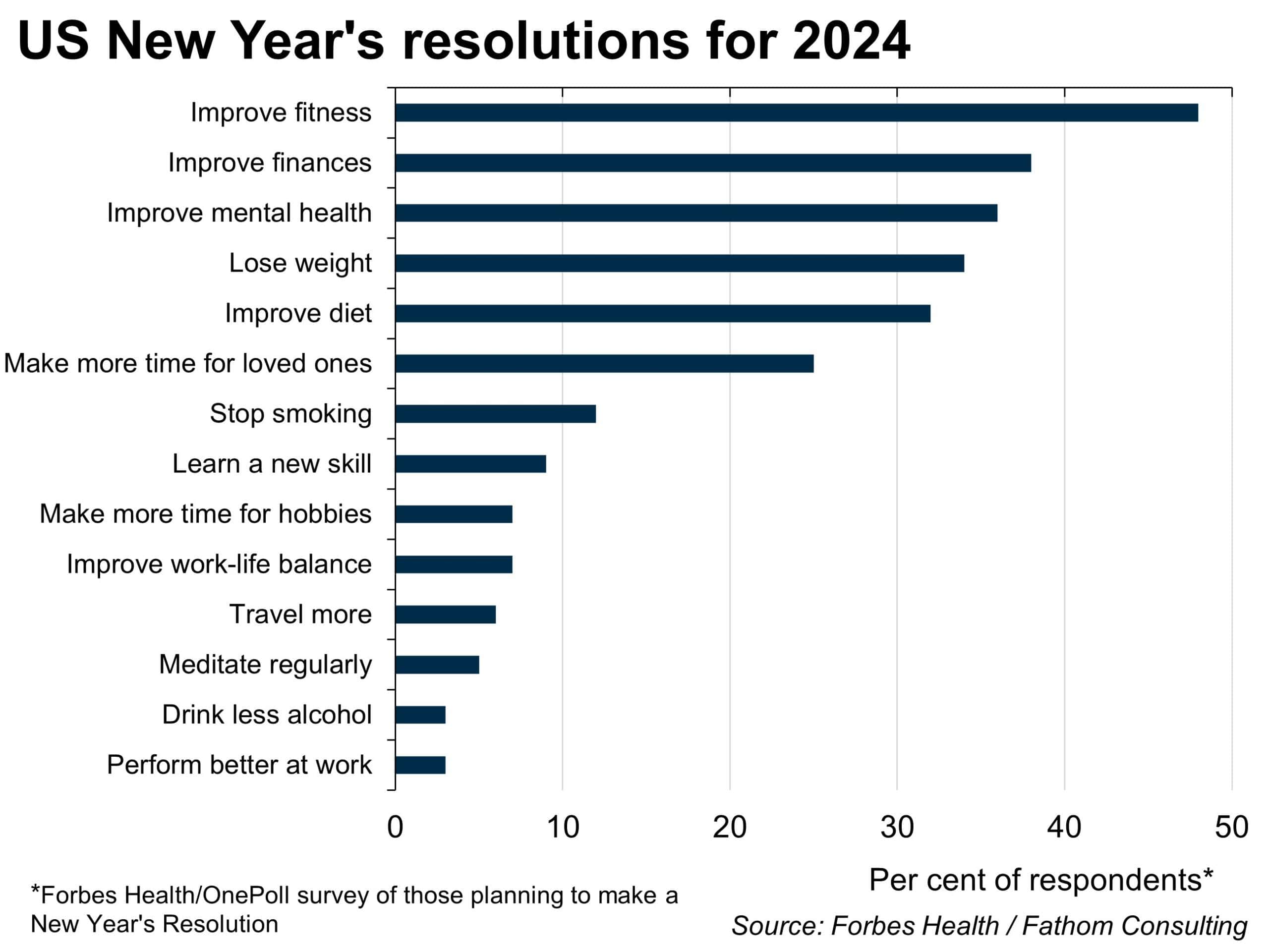

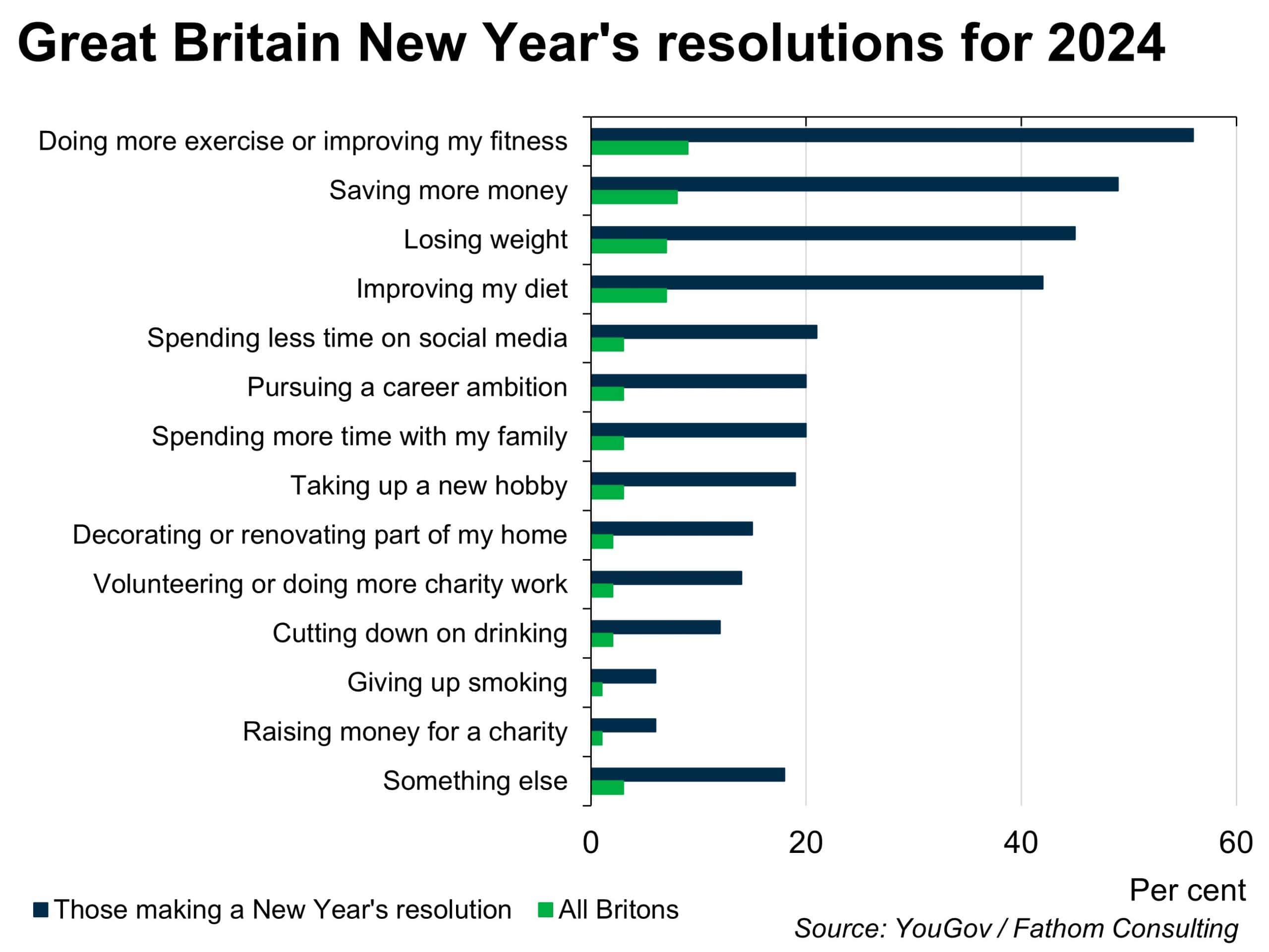

First, what are our resolutions about? According to a Forbes survey,[2] the top five New Year’s resolutions for 2024 in the US are to improve fitness (48%), improve finances (38%), improve mental health (36%), lose weight (34%) and improve diet (32%). It’s a similar picture in Great Britain, where the top five New Year’s resolutions are doing more exercise or improving fitness (56%), saving more money (49%), losing weight (45%), improving diet (42%), and spending less time on social media (21%), according to a YouGov survey.[3]

It is perhaps not surprising that people choose January to improve fitness and personal finances, with 30% of the least busy days at UK gyms in 2022 and 2023 being in December, and consumption peaking before Christmas. People are looking for a clean start after a month of indulgence, hoping that they’re able to keep new and improved habits in the year to come.

But do people stick with their resolutions? According to Forbes, 75% of New Year’s resolutions last five months or less, and are most commonly broken after two to three months. To identify the day when people start abandoning their resolutions, Strava compared activities posted on the app to its four-week average. In 2018, activity dipped below average on 17 January. Foursquare has another way of identifying the day where motivation turns: the point in time in which weekly visits to fast food restaurants increases at the same time as weekly visits to the gym decreases. In 2018, this was the second Friday of January.[4] In 2017 in the UK, 20% had already failed some of their resolutions by 6 January. In 2021, a survey[5] estimated that Americans spent US$397 million on unused gym memberships in a year. Looking at these numbers, it doesn’t seem like people have been very successful in keeping their resolutions — at least, not when it comes to being physically active.

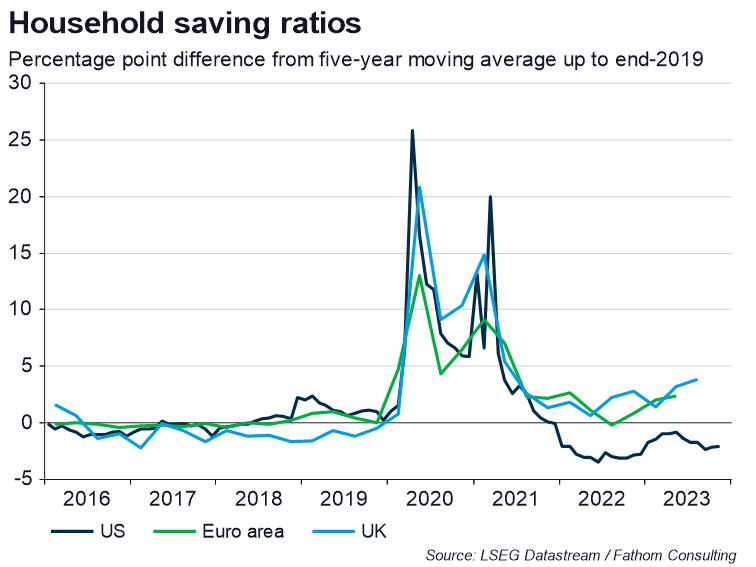

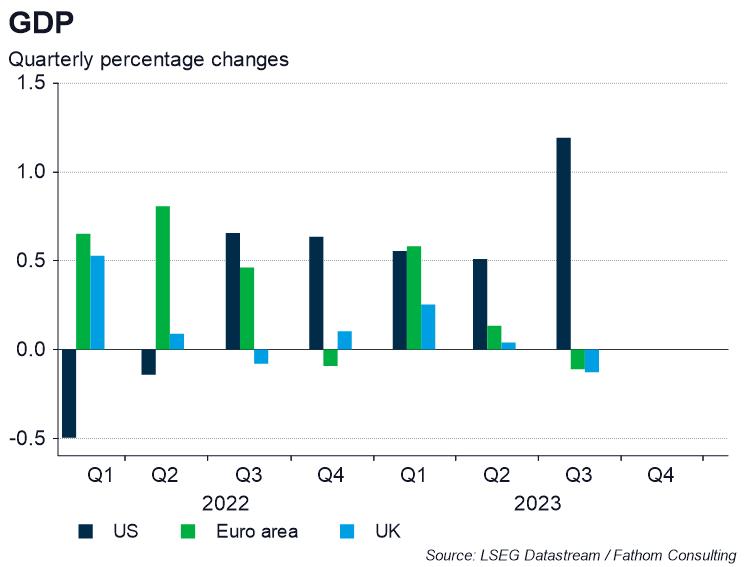

The resolution ranking second in both the US and the UK is to improve finances or save more money. This was also in the top five in both countries last year. In a curious way it’s a good thing that this resolution was quickly broken: Fathom has previously written about how the US citizen dipping into their pandemic savings last year helped drive the US’s strong GDP growth compared to the UK and the euro area, where economic uncertainty and high inflation prompted consumers to save more. This greater confidence among US consumers is reflected in the New Year’s Resolution survey results for 2024, which showed that saving more/improving personal finances was a more popular answer in Great Britain (49%) than in the US (38%). If the US consumer was to increase their savings and decrease consumption, this could lead to less GDP growth in the year to come. However, jumping to this conclusion purely on the basis of people setting New Year’s resolutions would be a mistake. After all, saving more was high on the list of people’s New Year’s resolutions last year, too. A survey by Fidelity Investments[6] found that inflation is the top reason cited by Americans as why they weren’t able to keep last year’s financial resolutions. Fortunately, with inflation falling in the US, real incomes and savings are increasing, making improving personal finances a more achievable goal in 2024 than in 2023.

Why don’t more people follow through on their New Year’s resolutions? One explanation can be what is commonly referred to as the ‘time consistency problem’ in economics. An example of this is a government’s promise to follow fiscal rules. A government might promise in the run-up to an election to stick to a fiscal rule and keep government debt at a low level. However, when actually in power, unexpected shocks to the economy may come along, calling for higher fiscal spending through increased borrowing. Another example is central banks using forward guidance to manage expectations of future interest rates. A central bank may use forward guidance to promise to keep future interest rates low for a certain period of time, and under certain conditions, to boost the economy. To ensure forward guidance is effective in managing expectations, central bankers need to stick to their promises. However, future events might make it optimal to raise rates quicker than promised. After COVID, for example, central banks chose to stick to the low rates they had previously promised, in the face of increasing inflation, and were then criticised for acting too slowly. So how does this relate to New Year’s resolutions? Being active and saving might sound like a great idea at the start of the year. But, there might be challenges throughout the year that makes it difficult to stick to your goals – such as prices increasing or long hours at work making it hard to fit in an evening workout. Just like with fiscal policies or forward guidance, it is difficult to pre-commit to a future target, especially if unexpected events occur.

Although this might have been a slightly negative take on New Year’s resolutions, I still think it’s worthwhile to take January to reflect on the past year’s achievements and plan for the year ahead. With more thought, we could avoid selecting goals that are bound to be broken a month into the new year, and set more attainable, perhaps shorter-term goals. While the weather and the short days keep us indoors, it is a good time to look at what milestones the past year has brought – whether that is graduating from university, starting a new job, moving into a new flat, starting a family, or winning new consultancy projects, to name a few. That way we can begin the year ahead in a positive frame of mind.

[1] https://www.puregym.com/blog/uk-fitness-report-gym-statistics/

[2] The Forbes Survey covers 1000 US adults: https://www.forbes.com/health/mind/new-year-resolutions-survey-2024/

[3] The YouGov survey covers 2054 GB adults: https://ygo-assets-websites-editorial-emea.yougov.net/documents/YouGov_-_New_Years_resolutions_2024.pdf

[4] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-01-16/here-s-how-quickly-people-ditch-weight-loss-resolutions

[5] https://finance.yahoo.com/news/americans-flush-397-million-abandoned-170105693.html

[6] https://preview.thenewsmarket.com/Previews/FINP/DocumentAssets/654557.pdf

More by this author