A sideways look at economics

“It’s more purposeful when you’re not just doing something for yourself, but for people who you don’t even know and have never met”

– South African rugby captain Siya Kolisi

Last weekend South Africa beat arch-rivals New Zealand 12-11 in the Rugby World Cup final. It is hard to explain to non-South Africans how much the win means to the people of South Africa, a country beset by problems and with a history of racial injustice and division, and how today’s rugby team, and especially its captain, are so inspiring. Some South Africans are now calling for Siya Kolisi to be President and for the rest of the Springboks to make up parliament. But are things other than rugby really that bad in South Africa, and what can we learn from this?

Siya Kolisi, South African rugby captain | photo by Stefano Delfrate 2022, Wikimedia Commons

I feel that clichés about the importance of sport get bandied round too much. And I say that as someone who loves sport. Sport is an outlet, a diversion and a hobby; there are more important things in life. But for South Africans, such as myself, rugby really does feel more than just a sport. Why?

South Africa was governed under a system of racial segregation, called apartheid, between 1948 and the early 1990s. Under this system, the majority black population, and other minorities of colour, were oppressed by whites. It was brutal: people of colour couldn’t vote, were not allowed to live in certain areas, or allowed to frequent certain public spaces. Any opposition to this system was put down with violence, sometimes death. Opposition leaders, such as Nelson Mandela, were incarcerated for trying to overturn this injustice. Many were killed.

Participation in sport was separated along racial lines too. Only whites could represent South Africa in national teams. Funding was given to white teams and to sports favoured by whites, like rugby, while little was given to black teams or sports preferred by blacks, like football. Because of international indignation at this system, South Africa’s sports teams were banned from competing internationally.

This changed when apartheid was dismantled. In 1995, South Africa hosted the Rugby World Cup and beat New Zealand in the final. The image of the by-then President Mandela wearing a green and gold rugby jersey as he handed the Web Ellis trophy to captain François Pienaar is legendary, although not without some controversy. To some, rugby was still a symbol of white oppression and Mandela should not have embraced that team, which contained only one black player. But Mandela, being the unifier that he was, saw no point in shunning the sport that his previous oppressors loved. Instead, he saw it as an opportunity to bring people of different races, and the country, together.

Had Mandela taken a different path, South Africa probably wouldn’t have won the cup last weekend. As it was, seven key players in South Africa’s 23-man squad were either black or of colour. Without Mandela, a young man like Siya Kolisi may not have decided to give a career in rugby a go. Siya, as he is affectionately called by South Africans, became the first black captain of South Africa’s men’s rugby team in 2018. He captained the team that won the World Cup in 2019, giving him legendary status. Last weekend he won it for a second time. Sho. [1]

What makes Siya so inspirational is the amount of adversity he has overcome to get to where he is today. He came from a township, growing up with nothing and no father around. He regularly saw his mother get beaten by other men. His mother died when he was young so he lived with grandmother, who died when he was young too. He would often go hungry. This is the story of so many South Africans.

To overcome all of that, and then get to the top of rugby, a white sport, as a black man, having to overcome racial barriers and stereotypes in the process, is a beautiful story. Not only that, but he is a fantastic player, speaks so humbly and recognises the opportunity, platform and responsibility that he has to bring other people a bit of joy. He is married to a white woman, something that would have been banned under apartheid, but shamefully something they have suffered racial abuse for more recently. He really is the face of modern South Africa.

There are other players in the team with similar stories and difficult backgrounds, which is why the rugby team evokes so many emotions for me and other South Africans. Sadness, because it is a reminder of the troubled past. Hope, because the path that Mandela took has inspired the likes of Siya to get to where they are today, and promises that there will be more people able to walk that path tomorrow. Respect, because you can see the determination in how these guys put their bodies on the line 100% in every game. Love and happiness, because it genuinely feels like this brings people together and diminishes racial boundaries. Admiration, because they had a plan and it worked.

The question I kept asking myself throughout the tournament was: how can Siya, and the rugby team, be so inspirational, while the state of the country and perception of its leadership be so bad? First of all, though, are things really that bad in South Africa?

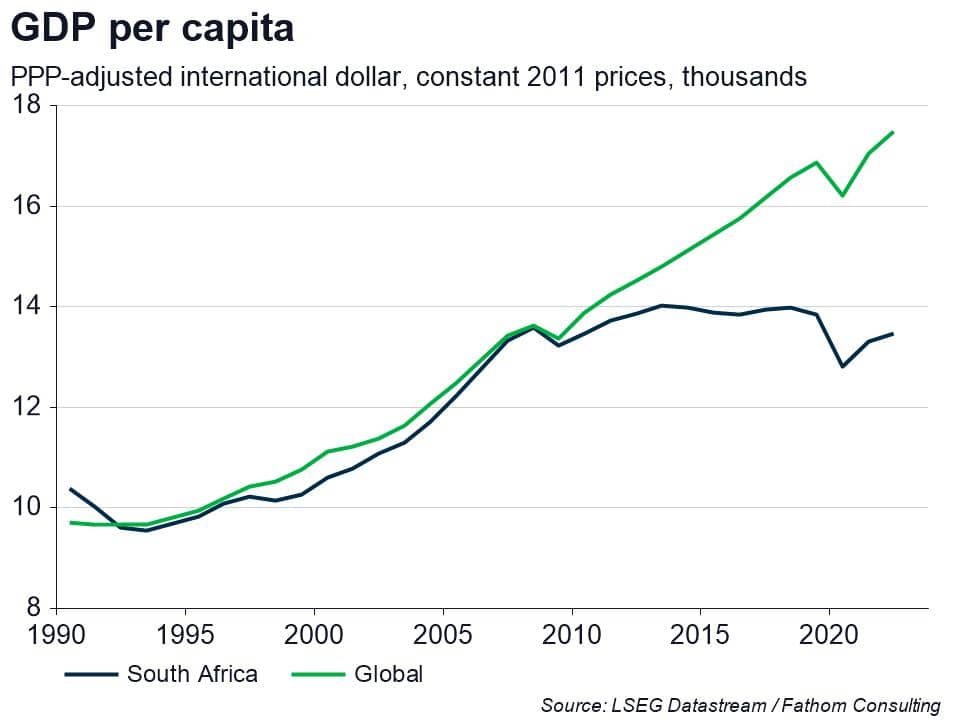

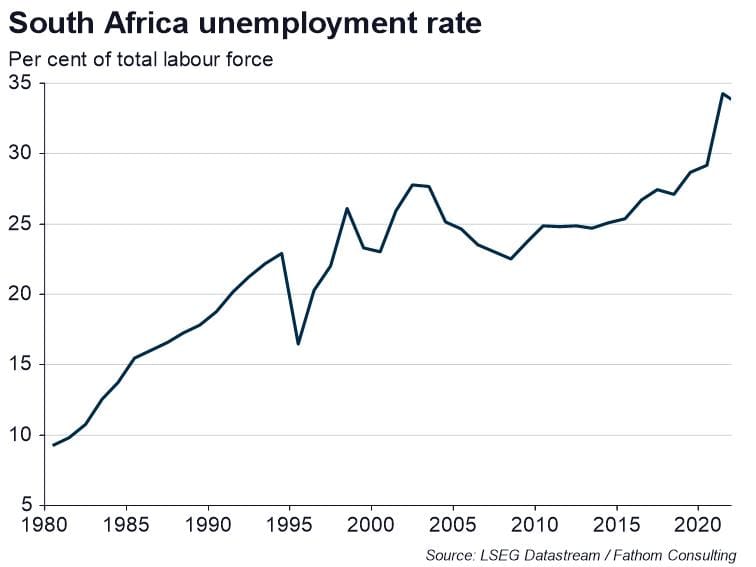

In many ways, yes. It is a beautiful country, and there are many great things about it, not least the vibrancy of its people. But on many measures of wellbeing, it is going in the wrong direction. Trend GDP growth has declined from more than 4% in 2008 to barely more than 1% now. South Africa’s share of world GDP has declined from more than 0.8% in the early 1990s to less than 0.6%. On a GDP per capita basis, things are even worse: it is lower in real terms now than it was in 2008, while global GDP per capita has increased nearly 30% over the same period. The unemployment rate has risen from 23% in 1994 to 33.5% in 2022. Nelson Mandela knew the importance of education, but South Africa spends a larger share of its GDP on education now and still has little to show for it. Many of South Africa’s economic and societal woes are a legacy of apartheid. But things are getting worse, not better — and the direction of travel cannot all be blamed on a system that was dismantled a generation ago.

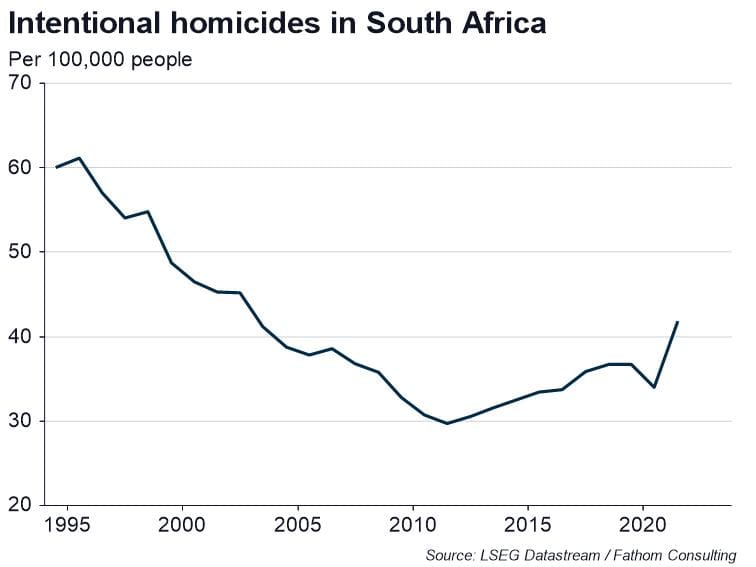

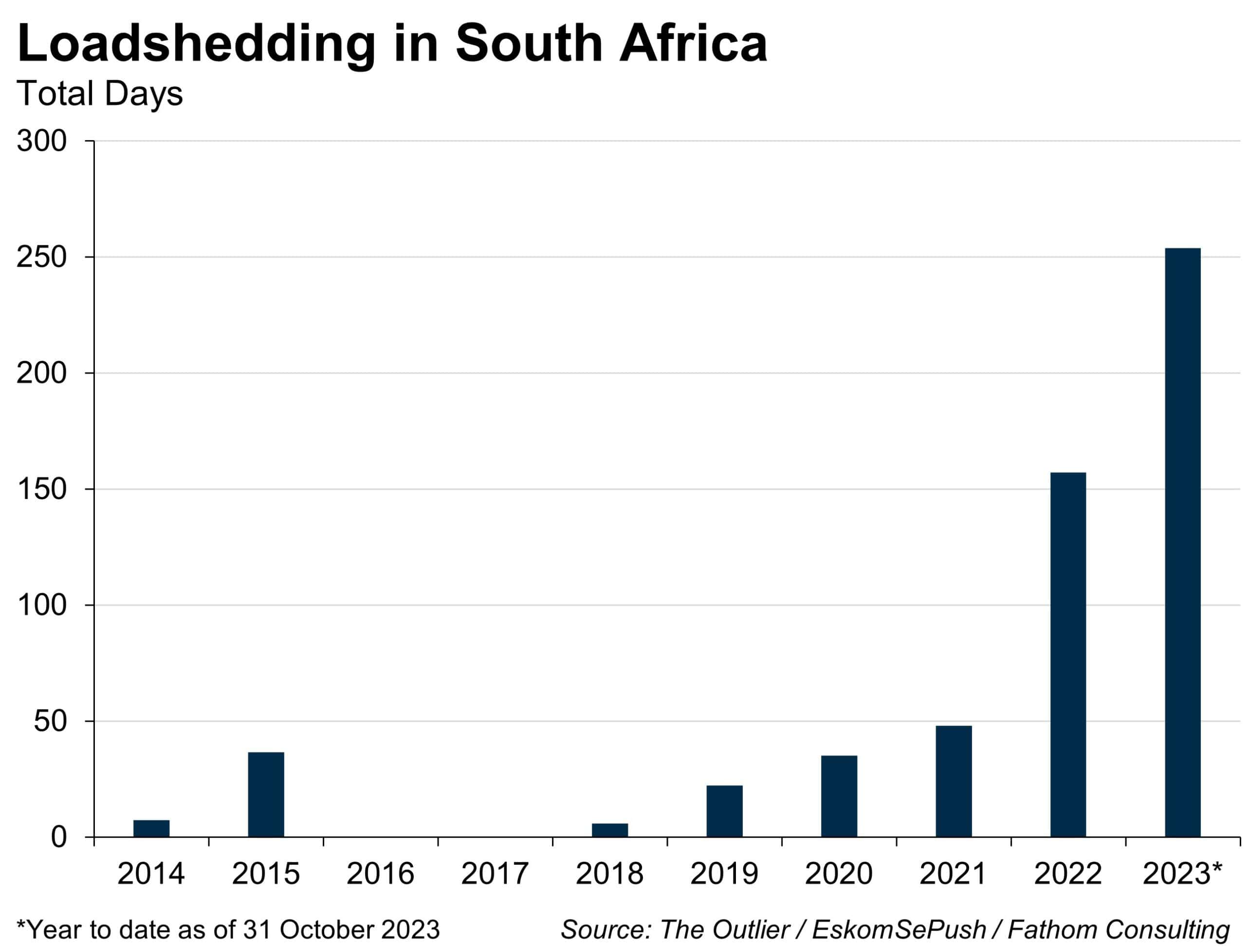

Admittedly, not everything is worse. The homicide rate, while still unacceptably high, is significantly lower now than it was in 1994 and South Africans, on average, live longer now than they did in 2005. But things can, and should, be so much better: for example, the management of the electricity network is atrocious. The country has had 254 days of interrupted electricity supply so far in 2023, and interruptions can last for hours at a time. André de Ruyter, the man tasked with sorting this out at the state-owned electricity company, alleged that corruption among senior ANC politicians was hindering his work. The day after he handed in his resignation he was allegedly handed a cup of coffee which unbeknownst to him was laced with cyanide – he drank it, but survived.

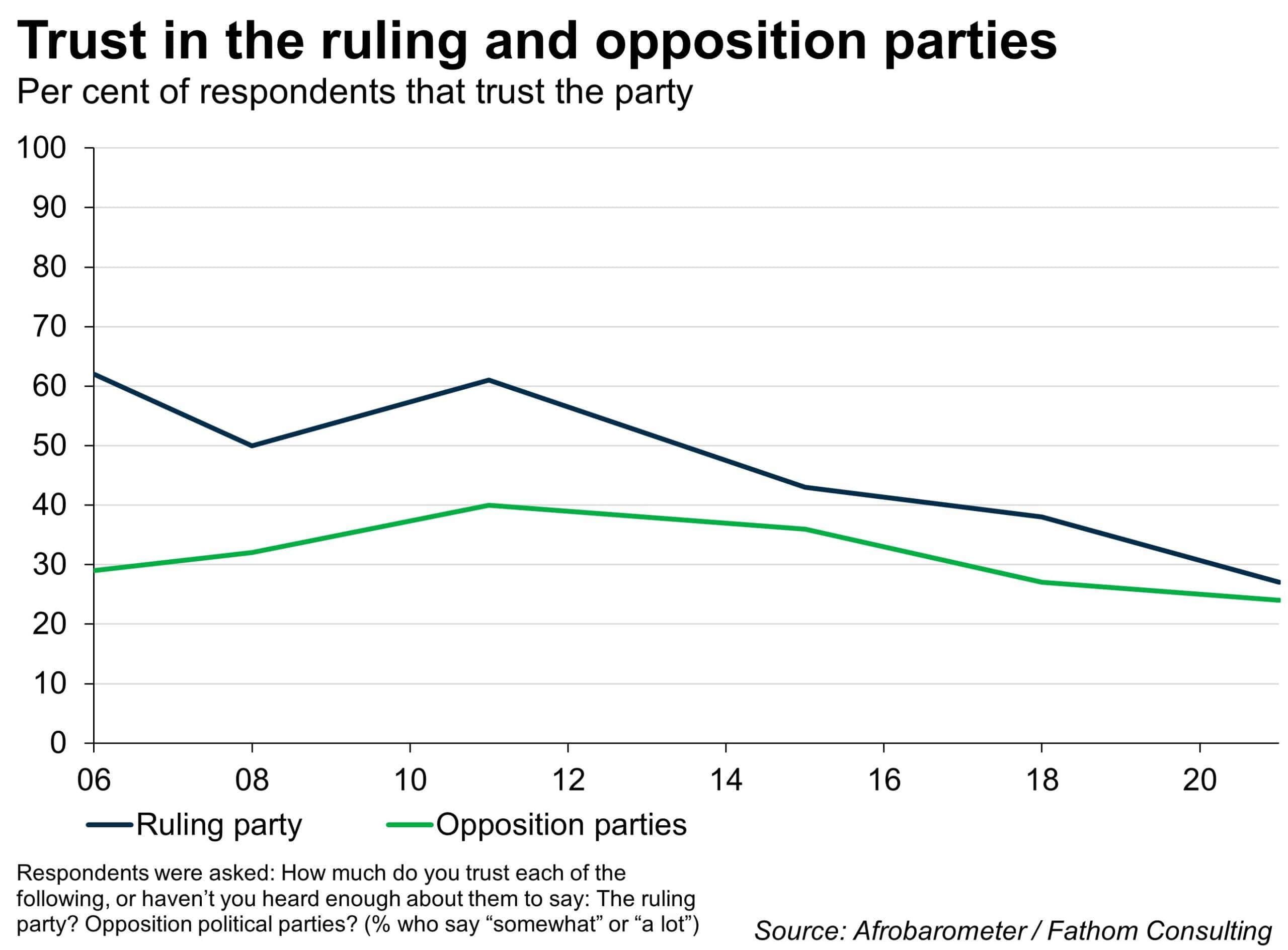

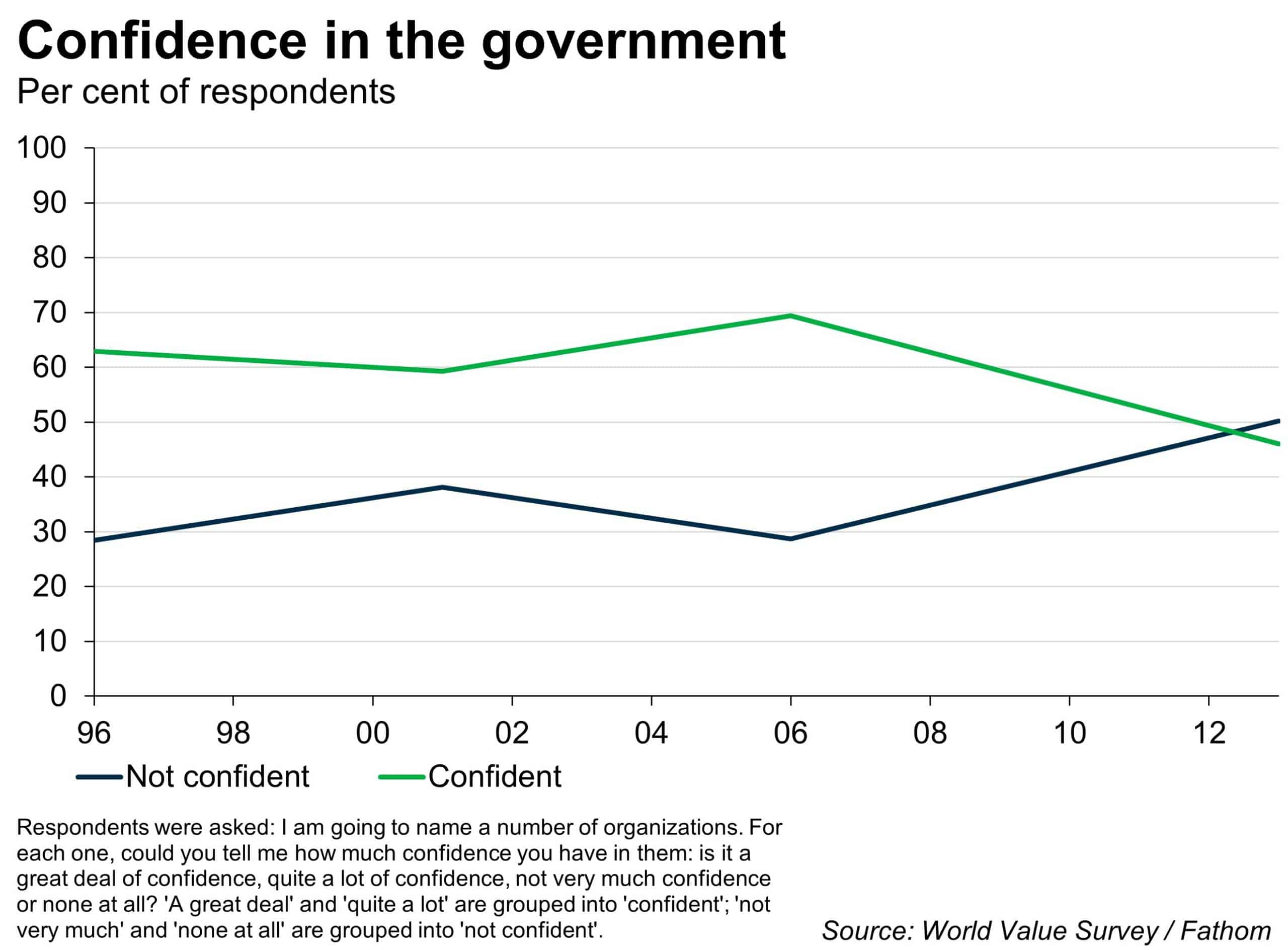

It is often easy to romanticise the past, but a range of objective indicators suggest that things are indeed on the wrong track. The whole of society needs to take some responsibility, but politicians more than most. Opinion polls show that my lack of faith in South Africa’s political leaders is shared by others, and that confidence in politicians, including the opposition, has been declining steadily.

Why is this so, and why are the leaders of today seen so poorly compared to the leaders who took South Africa out of apartheid? One South African told me during the tournament that he thought it was simply down to probability: great people come along every now and then, and South Africa got a larger-than-usual share in the 1980s and 1990s, but has a dearth now.

This could be true; but personally I think that circumstances have more to do with it. Circumstances, whether we like it or not, often bring out the best and worst in people. And circumstances dictate what we see, value and remember. Would Winston Churchill be a household name were he not a wartime leader? I suspect not. Would he be remembered for such leadership had the country not been facing an existential crisis? Perhaps not either. That is not to say that there are not many heroes that we do not know the names of and do not see. Small deeds, little things, can be heroic too.

But in terms of leadership, having such a strong cause, such clear motivation – like so many South Africans did during the struggle to end apartheid – can bring people together and harness determination, focus and selflessness in the population and its leaders. The Springboks managed this, I think, because they know how rugby can inspire those with very little and heal the wounds of South Africa’s troubled past.[2]

That is not to say that you need pain or suffering to motivate. The question is, how do normal people unlock such determination and selflessness in normal times? And how do politicians harness this when the problems they, and the country, face are not as clear cut as they are during war or overcoming a racist regime? I don’t know the answer, but I do think we need to recognise that sometimes people can get more satisfaction and motivation by doing things that are bigger than themselves. South Africa’s politicians would do well to remember that. It’s something that economists might want to reflect on too.

[1] South African slang for ‘Wow!’

[2] To get more of a sense of this I highly recommend the documentary, Chasing the Sun

More by this author

Russia, China and their no limits friendship