A sideways look at economics

During a recent birthday trip to County Mayo, I spent an afternoon in McDonnell’s. The locals know it as ‘The Lobster Pot’, given the difficulties some face in leaving once inside. Newcomers are shaken by the hand and welcomed to Belmullet by Padraig, the affable owner, and the regulars ensure no-one stays a stranger for long. Like any honest boozer, there is no food menu. But there is food. At the end of the all-Ireland Gaelic football final,[1] fresh sandwiches appeared for customers to share. Later, there was a round on the house to commiserate when Mayo’s footballing rival won the Sam Maguire cup. One December evening a few years ago, the Guinness and Jameson that my brother and I had each ordered were refilled for free as Padraig wished his patrons a happy Christmas. As the turf burned, live music and seasonal cheer filled the air, it became clear we would not be making it home for dinner. In a country known for good craic and bad weather, the Irish pub makes sense and is a popular export. However, with effective policymaking over the past 40 years, there’s a lot more to the Irish economy than that.

Ireland used to be poor by northern European standards. The country has a painful history of emigration, and when my dad graduated from university in 1978, he and his friends went abroad, motivated to a large extent by economics. Many came to London. At the time, Ireland’s GDP per capita was almost a third below the UK’s, and its unemployment rate was almost double. Economic conditions got even worse in the decade that followed, with joblessness peaking at 16.8% in the late 1980s. It wasn’t just the economy. Ireland, a fiercely Catholic nation, was seen by many young people at the time as extremely conservative. I’ve met several from that generation who left and have no interest in returning to a country they remember as backward in its views.

The economy has improved since then, with the two main political parties following a fairly orthodox set of policies: invest in human and physical capital and open up the economy to international trade. The EU single market came into force in 1993, and policymakers gripped the opportunity with both hands. Irish exports, which had been disproportionately destined for the UK, increasingly went further afield. The share of merchandise trade in GDP soared, too, peaking at , as goods exports rose from 29 billion USD to 77 billion USD.

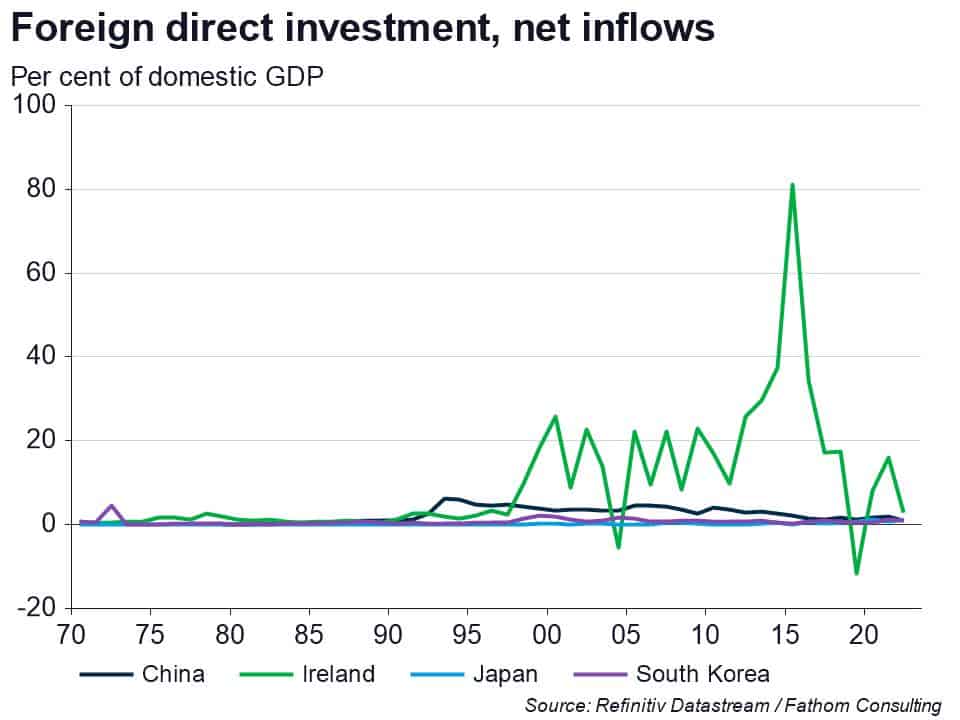

The government made an active attempt to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). Ireland’s headline corporate tax rate was 40% in 1993 when the single market began, and this was steadily reduced, falling to 24% by the end of the decade and 12.5% in 2003. This policy alongside membership of a large internal market was a magnet for FDI, with net inflows dwarfing figures seen in East Asia when scaled against GDP. By 2022, just over 300,000 people were employed by multinational companies, representing 12% of total employment.

It is not just taxes that attract foreign investment, but high levels of human capital too. It’ll come as no surprise to readers who enjoy the work of Yeats or Wilde that the country does well on verbal reasoning, with Irish students ranked 4th out of 36 OECD countries for reading literacy. Results are less impressive for maths, where students were 16th out of 37, but that average seems to mask concentration at higher levels. EU data show that the country ranks highest in the union for graduates per capita in STEM subjects.

From being a relatively poor country for the EU, Ireland is now relatively rich — yes, that is true even when one accounts for the distortions in its GDP data. Indeed, to some extent it’s a victim of its own success. Investors in Irish property drank the Celtic Tiger kool-aid, resulting in a long period of austerity after property prices crashed back to earth. Even with economic recovery since then, the high cost of housing is widely seen as a public failure. A relative who recently graduated didn’t emigrate like his mother, but does LAH (live at home) due to the high price of Dublin housing. Indeed, I routinely get sticker shock at the shops when visiting; for good reason, Ireland is the most expensive EU country for a basket of goods and services.

It’s not just the economy that has been transformed but civil society too. Catholicism remains the dominant religion, but no longer dominates society. In 2015, Ireland became the first country in the world to vote in a referendum to legalise same-sex marriage. A few years later, in a landmark plebiscite, two thirds of voters were in favour of overturning a longstanding constitutional ban on abortion. I was in Dublin when news of Sinéad O’Connor’s death broke. She had experienced a tortured relationship with her home country, including after ripping up a picture of the pope in 1992. In the next few days, I heard many people lament that it was a shame she wasn’t around to hear the nation’s posthumous outpouring of love. Her views on child abuse, homosexuality and women’s rights, which were controversial at the time, have become mainstream. I couldn’t help but think she was the right person born in the wrong Ireland.

Ireland remains imperfect but it has made big strides in recent decades – both economically and socially. In a world where it is easy to be pessimistic, it’s a good example of how a country can transform itself for the better in a generation. So, if you ever find yourself on the Wild Atlantic Way, stop in at The Lobster Pot. Just make sure you don’t have anything else important booked that day. You might find it difficult to leave. Sláinte!

[1] Gaelic football is a fast-paced sport that is a mix of football and rugby. Mayo has suffered eleven final defeats since winning in 1951, when a priest put a curse on the county after a bus carrying the victorious players home didn’t stop to pay their respects at an on-going funeral: “For as long as you all live, Mayo won’t win another All-Ireland.” The last surviving player died in 2021, but Mayo has still to win.

More by this author