A sideways look at economics

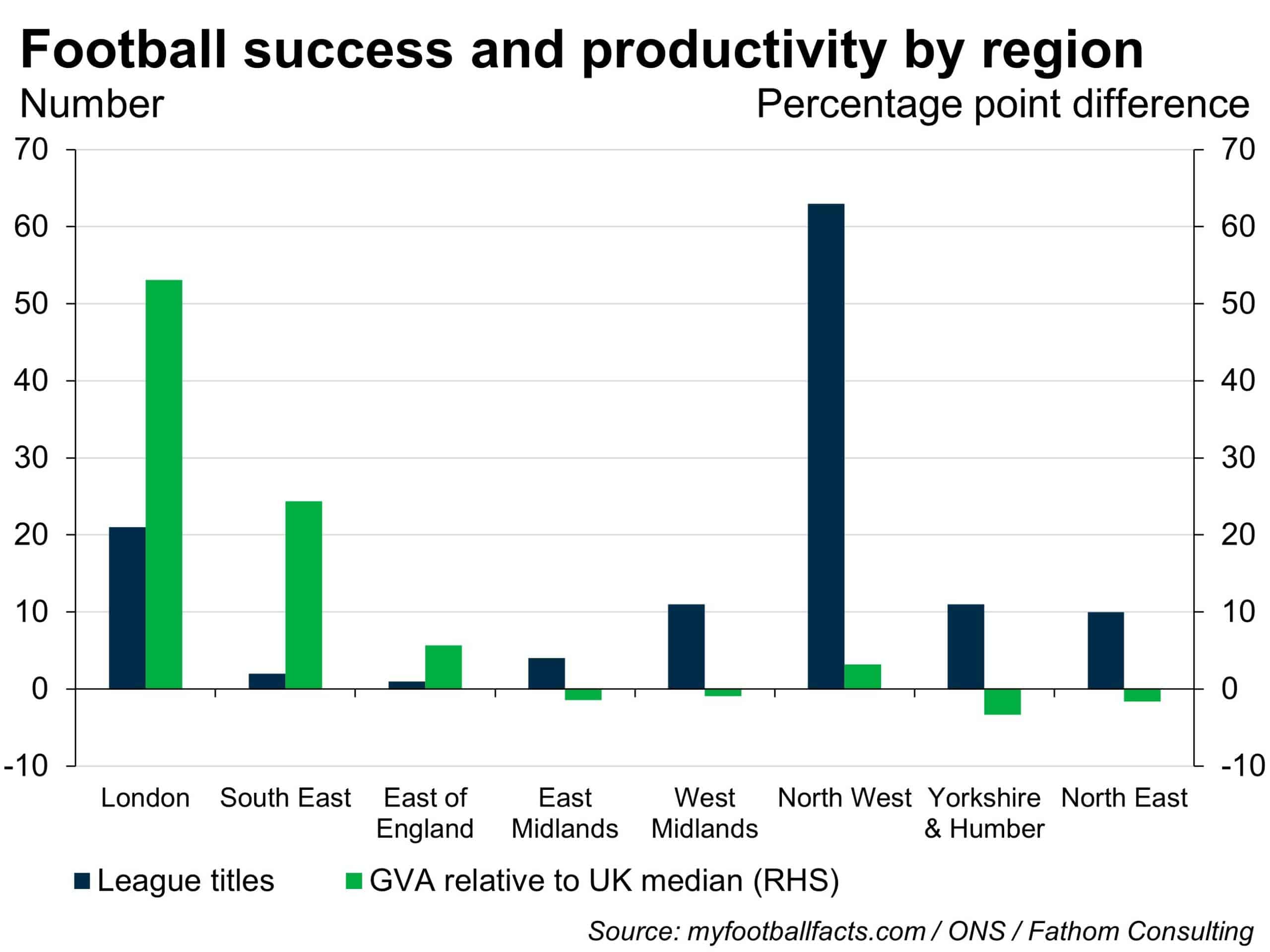

England’s two most decorated football clubs renewed their rivalry last Sunday, with Manchester United suffering a defeat of humbling proportions to Liverpool. This United fan has had dodgy oysters that were easier to stomach than conceding seven at Anfield. While these two historic clubs are not at the summit of the Premier League this season, they boast the country’s largest collection of domestic and European honours. If footballing productivity is judged by league-winners’ medals per head, the North West is out on its own.[1] Fans of these clubs do not agree on much, but would probably concur that this is a welcome respite from the London-centricity of some other aspects of British life. Regional economic inequalities in the UK have become significant enough finally to elicit a government response, but so far that has delivered little more than a vote-winning slogan: ‘levelling up’. Two years after the election, a YouGov poll suggested that half of us were still unsure what that term actually meant.

Key to these regional differences in economic prosperity is productivity growth: London is roughly 50% more productive in terms of GVA per hour than the average UK region. The UK’s regional differences are more pronounced than service-based peers: London is 41% more productive than Manchester, compared to a 26% difference between Paris and France’s second city, Lyon. Despite this, London has not been immune to the UK’s overall productivity puzzle, with productivity growth in the capital non-existent since the Global Financial Crisis.

Capital cities tend to be the most productive,[2] and particularly so in service-based economies. There is universal agreement on the role of agglomeration effects in boosting productivity, with companies enjoying benefits from clustering together. London’s prosperity has attracted skilled workers while productivity is also positively correlated with the level of foreign direct investment and trade. Given its proximity to continental Europe and historical importance as a commercial centre, London has clear advantages.

There are other, perhaps less justifiable, reasons why the capital’s productivity is so much higher, such as its superior infrastructure and higher level of public R&D spending. These factors have not just fallen from the sky: they are policy choices. Capital spending on transport in London was £672 per person in 2021/22 — £286 per person more than the English average. Meanwhile London and the South-East receive 41% of English public R&D investment, despite representing only 32% of the population.

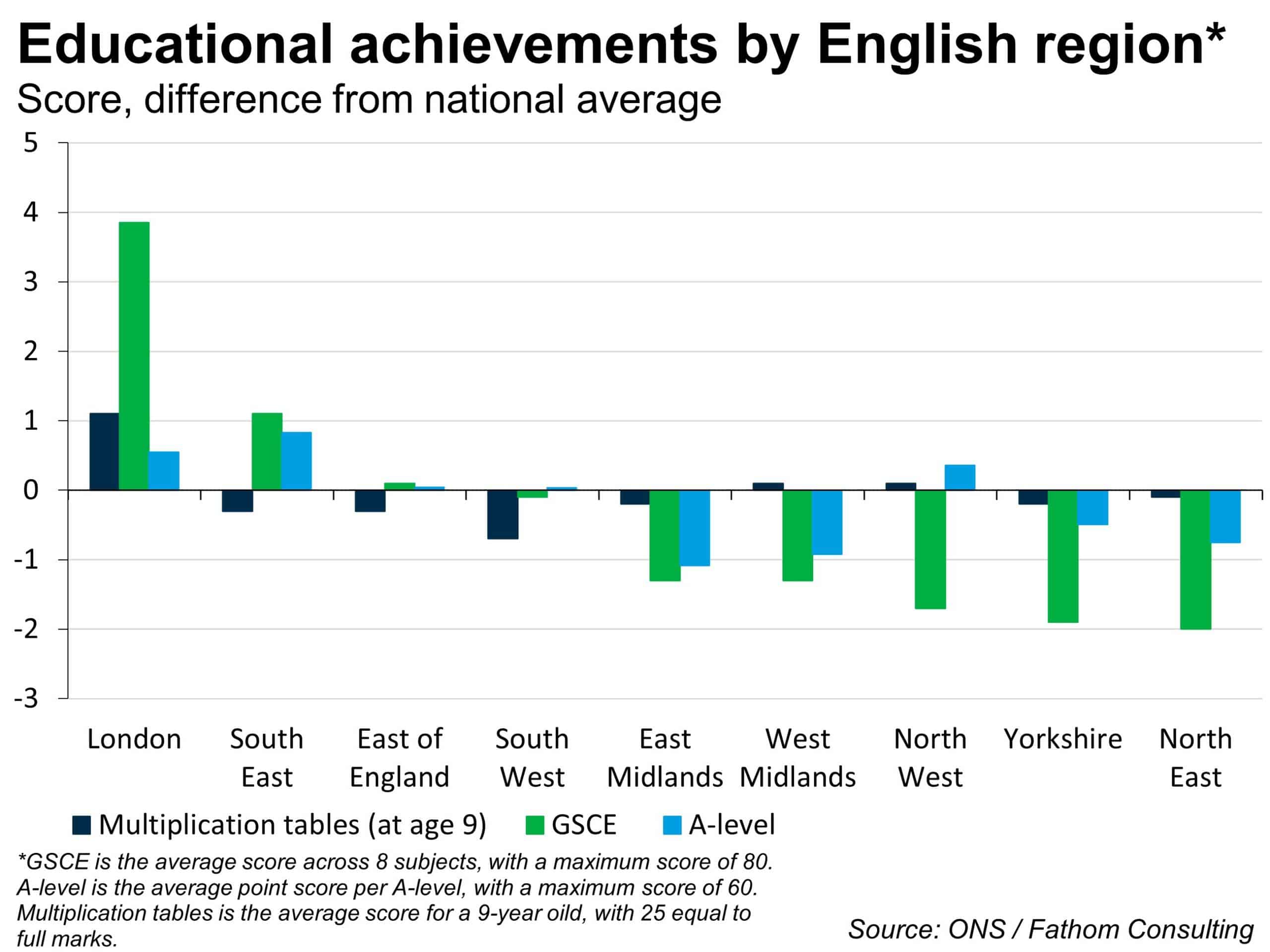

Policy decisions have also helped to deepen London’s talent pool. While graduates are moving to the capital, regional gaps in skillset are being reinforced by differences in educational attainment. The education system needs to actively fight against regional inequalities, delivering the best outcomes in the UK’s worst performing regions. It is doing the opposite, with the best results at every age range being achieved in London and, to a lesser extent, the South-East. Meanwhile, 59% of under-25s in London go on to higher education, 12 percentage points higher than the national average. University fees for English universities were trebled in 2012 and are the same regardless of a student’s regional background, acting as a greater disincentive to continue education in lower-income areas. Maintenance grants were also abolished in 2016, meaning even higher levels of debt for the poorest students.

In terms of overall spending, the UK is effectively run as a transfer union, with London and the South-East running a fiscal surplus and most other regions a deficit. Rather than seeking to address these regional differences through higher capital spending in these underperforming regions, government policy has accentuated them. Capital spending per head in London last year was 42% higher than the UK average. Since the 1980s, successive UK governments have left regional development to the guiding hand of the market. With the benefit of hindsight, that seems a mistake. The task of governing is not just a choice of the appropriate level of redistribution.

To avoid making ‘levelling up’ simply a matter of reallocating income from some parts of the UK to others, it is essential that the emphasis is on growth, making that economic pie bigger. Two other historic northern rivals, Sir Tony Blair and William Hague, last month jointly set out the need for government to turbo-charge a new ‘high-tech Britain’, with greater investment in research, higher participation in STEM subjects and the embrace of new technologies in public services. Securing Britain’s role at the forefront of the technological revolution and raising aggregate UK productivity will take ambitious policy. Similarly pro-active policy is needed to tackle regional inequalities. As Fathom’s Chief Economist recently argued, the simplest way for the UK government to raise productivity is to increase public R&D spending. If that option is pursued, it could be predominantly allocated outside the South East for a change.

A panel of 24 UK economists was recently asked which policies would help to address regional differences.[3] The common theme to their answers was money — addressing regional productivity involves cold, hard cash being invested. The problem is, UK now finds it more expensive to fund these projects. That is partly down to the brief reign of Liz Truss, which resulted in a spike in the UK’s real long-term borrowing costs that has yet to reverse.

Nevertheless, with the Premier League trophy looking like it might take a rare trip south down the M1 this year, the time is ripe for action on non-sporting inequalities. Next week’s budget might tell us how serious the government is about this task.

[1] Manchester City and Everton have won the fourth and fifth most top division titles in England.

[2] https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/0cb8a757-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/0cb8a757-en

[3] https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/levelling-productivity-gaps-uk

More by this author