A sideways look at economics

After two years living in charming Kraków, I decided it was time for a change. A few options were on the table, but London stood out thanks to its astonishing historical architecture, rich cultural offer, endless leisure activities and cosmopolitan environment. Finally, as an economist I couldn’t resist the appeal of working in one of the biggest financial hubs in the world — definitely an experience worth having. The decision was made, but where should I start? And most importantly, would I fulfil my goal?

I have to admit that I was a bit wary about my chances. At the end of the day, it was London: the competition for securing the best jobs was bound to be fierce, I reasoned, since so many other people also wanted to live there and enjoy the enormous advantages that the city has to offer. The fact that I was coming from outside the UK put me at a clear disadvantage compared to UK-based candidates, as employers need to sponsor you for a visa, a process that can get quite lengthy and is both bureaucratic and financially unpleasant.

However, once I brushed up my CV and started the job search, my experience turned out to be quite different from what I was expecting. The number of vacancies posted on LinkedIn for ‘Economist’ jobs in London was strikingly high, with a great menu to choose from, ranging from banks, consultancies, and investment management firms to the public sector. As I sent out my first applications, I was glad to observe that my profile was getting a lot of attention, which made me ask myself: is this happening because I am ‘special’ or is there something else going on here?

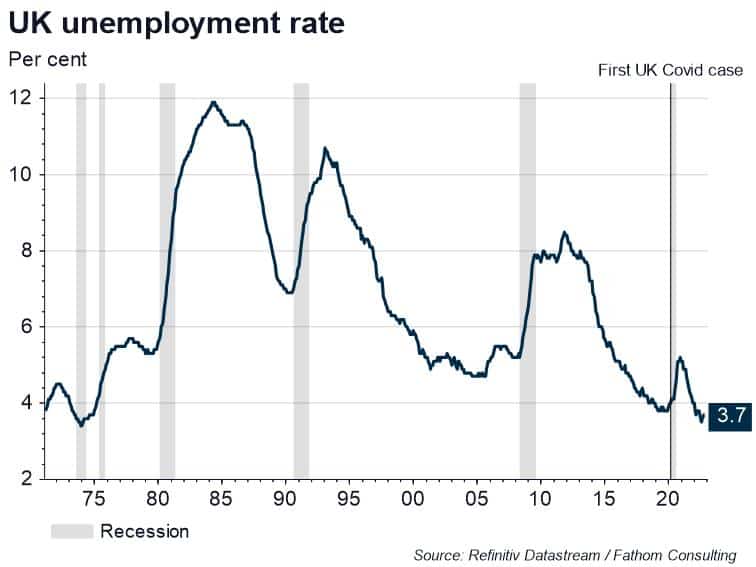

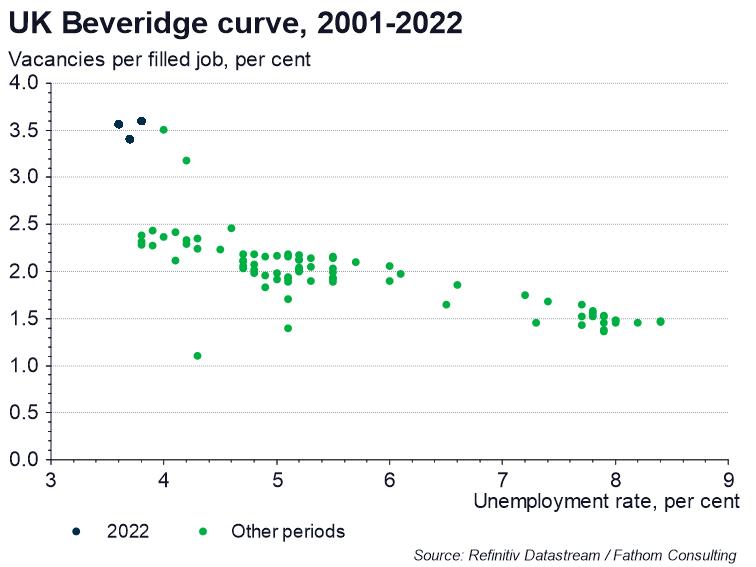

It makes sense to start answering this question by looking at the general picture of the labour market in the UK. As we can see in the chart below, the unemployment rate currently stands at 3.7%, the lowest level since 1974. Another interesting measure to look at is the so called ‘Beveridge curve’, which relates an economy’s unemployment rate with its job vacancy rate. The idea is that, during recessionary periods, the unemployment rate increases and the number of jobs available falls (and the opposite for boom periods). We can see that this relationship held very well in the UK until the COVID crisis, when the number of vacancies fell sharply as a consequence of the lockdowns, while the unemployment rate stayed at exceptionally low levels (government support played a key role here). Since the reopening of the economy in 2021, there has been a surge in vacancies while unemployment has remained low, and the Beveridge curve has now become vertical. In other words, we are in a very tight labour market.

What are the reasons for this anomaly? Fathom’s research into the issue suggests that the current tightness in the labour market is mainly due to a reduction in labour supply,[1] a change that we attribute to two main factors. The first is that many European citizens (we estimate up to a million) left the UK during the pandemic but have not come back, likely for reasons related to Brexit. The second factor has to do with a lower participation rate in the labour market, particularly among older age groups. This could be due to a combination of early retirement (due to higher savings built up during the pandemic) and ill health, with many people facing Long COVID.

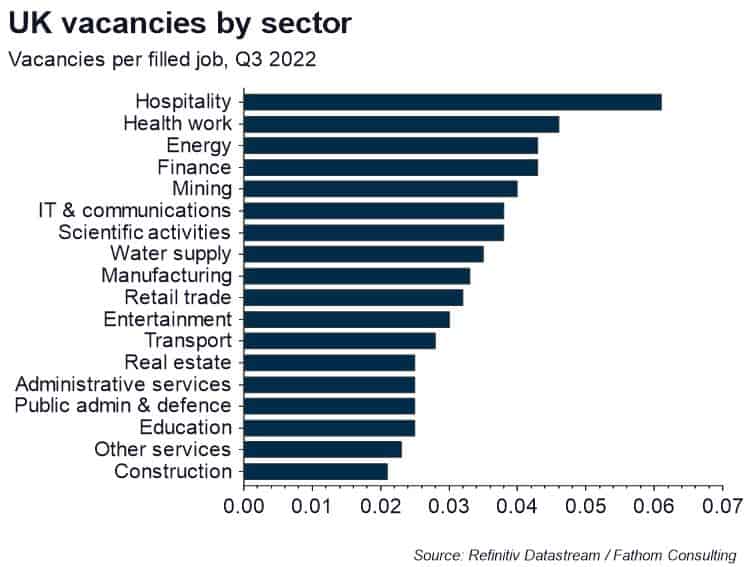

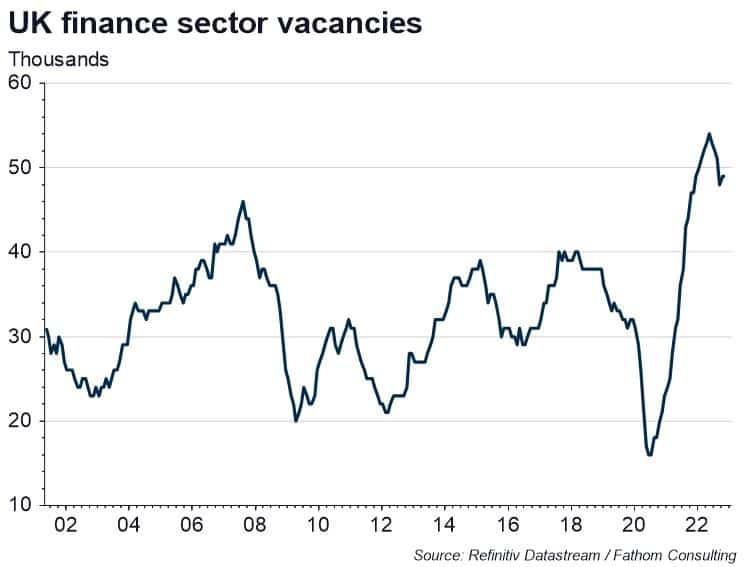

So far, we have been very general; so it is now worth looking in a bit more detail at what interests us, ‘Economist’ jobs. Are these also being affected by the current labour market tightness? And if so, to what extent? If we look at the number of vacancies per filled job, we find that finance is the sector with the fourth highest rate of vacancies — not far behind the health sector. Furthermore, looking at the historical number of vacancies for the sector, it is currently at the highest level that it has ever been.

The UK government is aware of this situation and has established a list of “shortage occupations”,[2] which offer some advantages when it comes to obtaining a visa. In particular, for these occupations you are allowed to come if you get paid only 80% of the usual floor salary[3] for that particular sector; in addition, the visa may be processed faster and the application fee is cheaper compared to a non-shortage occupation. For example, a visa for 3+ years for an economist costs £943 instead of the standard £1,235 for high-skilled workers (yes, we economists are also considered high-skilled!). Given the data we have looked at, it is not surprising that economists are currently included in that list.

I don’t know about you, but the conclusion I reach from this brief analysis is that it’s an excellent time to work as an economist in London. Odds have never been higher that you will have plenty of opportunities to choose from and that your job hunt will end successfully, even if you are coming from outside the UK. In regard to myself, I am glad to report that my job hunt was successful, my visa came through within one month and I am now settling in well at Fathom. However, I have to admit that these findings leave me with a bittersweet taste — as it’s time for me to realise that I am not so ‘special’ after all!

[1] Supply and demand shocks are decomposed using a structural vector autoregressive (SVAR) model following the Blanchard and Quah (1989) approach, finding that negative shocks to aggregate supply have reduced potential output in the UK by 4% relative to trend.

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/skilled-worker-visa-shortage-occupations/skilled-worker-visa-shortage-occupations

[3] There is a “floor” or “minimum” salary that an employer will need to pay you to qualify as a skilled worker, which varies by sector

Read last week’s TFiF: