A sideways look at economics

As children in the early noughties, my brothers and I would take any opportunity to relentlessly petition our parents to buy us a pack of Pokémon cards. We would offer deals such as promising to clean our rooms, or argue (with absolute honesty of course) that our friends’ parents were buying them hundreds of cards and they couldn’t possibly want us to be left out! Whichever method we chose, it rarely worked.

Now that I’m older I can only laugh at the frustration we must have put them through. That said, given the jump in the value of old Pokémon cards during the pandemic, perhaps they should have listened to us! Our parents, however, were no doubt aware that crazes like this come and go. One day it was Pokémon, the next it was World Cup sticker books or stuffed toys. They all wound up being thrown away eventually. But what drove us to want these cards?

Psychologists offer several theories to explain what influences our consumption behaviours. Many of them attribute outside influence; for example, reinforcement theory, a well-practised method of parenting. If a child is good the parent will reward them and if they’re bad they will be disciplined. This is done in the hope that, over time, the child will associate behaving better with the feeling of being rewarded. While this behaviour has influence throughout our life, it acts most strongly while we are young, before our brains have fully developed and our experiences are limited.

Unfortunately, this behaviour makes us exploitable. And no surprise… companies do exploit it. In the same way as parents guide their children, companies condition us into repeat purchases. For example, by issuing rewards cards they incentivise their customers into buying more, in return for the certainty of future discounts. However, the effect does not work indefinitely: when we are able to reliably predict reward delivery (like the certainty of a rewards card, or even an annual bonus), research has shown that our conditioned cues become neutral — i.e.. we treat it less as a reward and more as the norm. The dopamine gain from these rewards is then diminished.

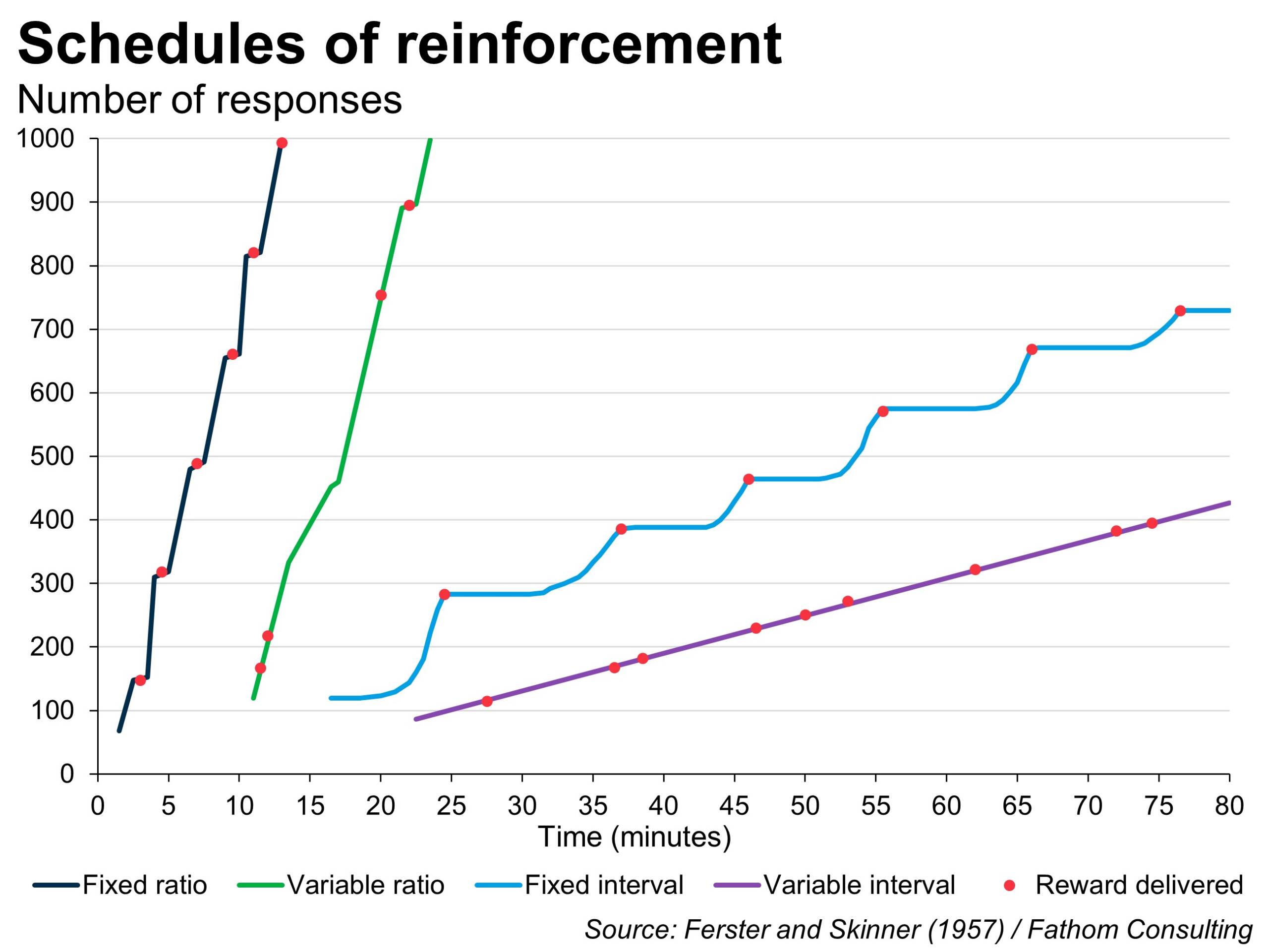

A study has looked into how the schedule of rewards (their frequency and triggers) affects both how hard living organisms such as rats worked for the reward (i.e., the rate of their responses to a given task) and how quickly they stopped participating in the experiment. The first scenario was a fixed ratio schedule. Like collecting stamps on a loyalty card, a reward was given every time a task was completed a set number of times. The researchers then modified this to a fixed interval schedule, i.e., rewarding a task only once a certain amount of time had passed since the last reward. This resembles how most of us are paid our salary. The ratio schedule produced much higher response rates than the interval schedule — implying that, where possible, being paid for the amount of work carried out incentivises us to perform more efficiently than a monthly salary.

The most interesting results, however, came when researchers removed the certainty from each scenario. Now, instead of a fixed schedule, rewards were paid for a task after a random number of responses (a variable ratio schedule) or a random length of time (a variable interval schedule). The rats would not know how many times they would have to complete the task or wait until a reward was paid out. Instead of being disheartened by the lack of instant gratification, the rats’ willingness to engage in the task became much more sustained in both scenarios, and at a steadier rate. The variable ratio schedule, whilst also eliciting a high rate of response, was the most resistant to the rats giving up.

Which scenario sounds the most like buying Pokémon cards?

Ding ding ding, it’s the variable ratio schedule! Now, I’m not saying we all behave like rats, but we do experience similar dopamine releases when rewarded. The constant desire of my brothers and me to buy more packs of Pokémon cards was driven by the randomness of the reward (the reward being the rarer, shiny cards). In much the same way, gamblers at a casino are inclined to play as many times as they like, drawn by the lack of certainty of a payout. The pull my brothers and I had to buy Pokémon cards is the same pull that gamblers experience to a casino. Thankfully, it seems our parents’ frugality saved us from an addiction to these flimsy bits of card.

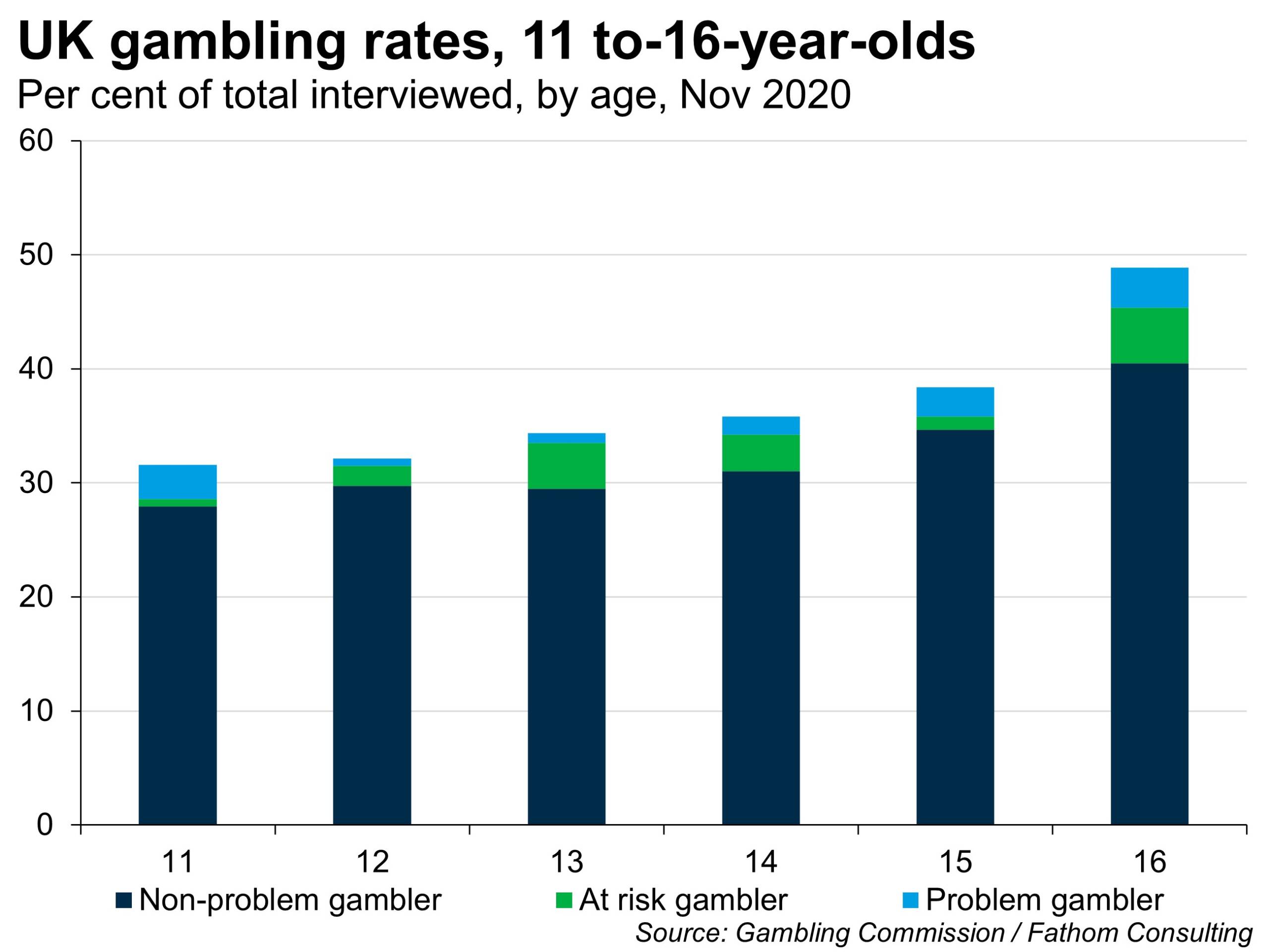

In all seriousness, though, marketing tricks like this are contributing to a concerning trend. From 2016 to 2020, the percentage of 11-16 year olds classified as problem gamblers, the most severe classification, has risen fourfold to 1.9%. By comparison, the rate of problem gamblers over 16 in the year up to March 2020 was 0.6%. The Royal College of Psychiatrists reports that problem gamblers are more likely to develop stress-related disorders, substance abuse and depression, whilst also performing worse at school with increased rates of expulsion. UK law restricts most gambling to over 18s. There are understandable exceptions. Low stake, low reward machines such as coin-pusher or crane-grab machines, which have maximum stakes of £1, are allowed at any age and I’m sure most would agree this is acceptable. However, there is a growing industry capitalising on blind spots in the regulations, such as the lack of restrictions within video games.

Five years ago, I would never have argued that buying Pokémon cards could amount to gambling. But the line is becoming blurred. As the “hype” around these cards has risen, so too has the value of the rarer cards. Last year a single card was bought for over $5 million. Granted, this is the extreme, but cards that you can find today could be worth hundreds of pounds. I am not advocating the regulation of collectible card games. In fact, last year, research found little correlation between spending on these cards and problem gambling. However, it does bring a less innocent aspect to what was designed as a game for the young, increasing the incentive to buy these packs, not just for fun but in the hopes of turning a profit.

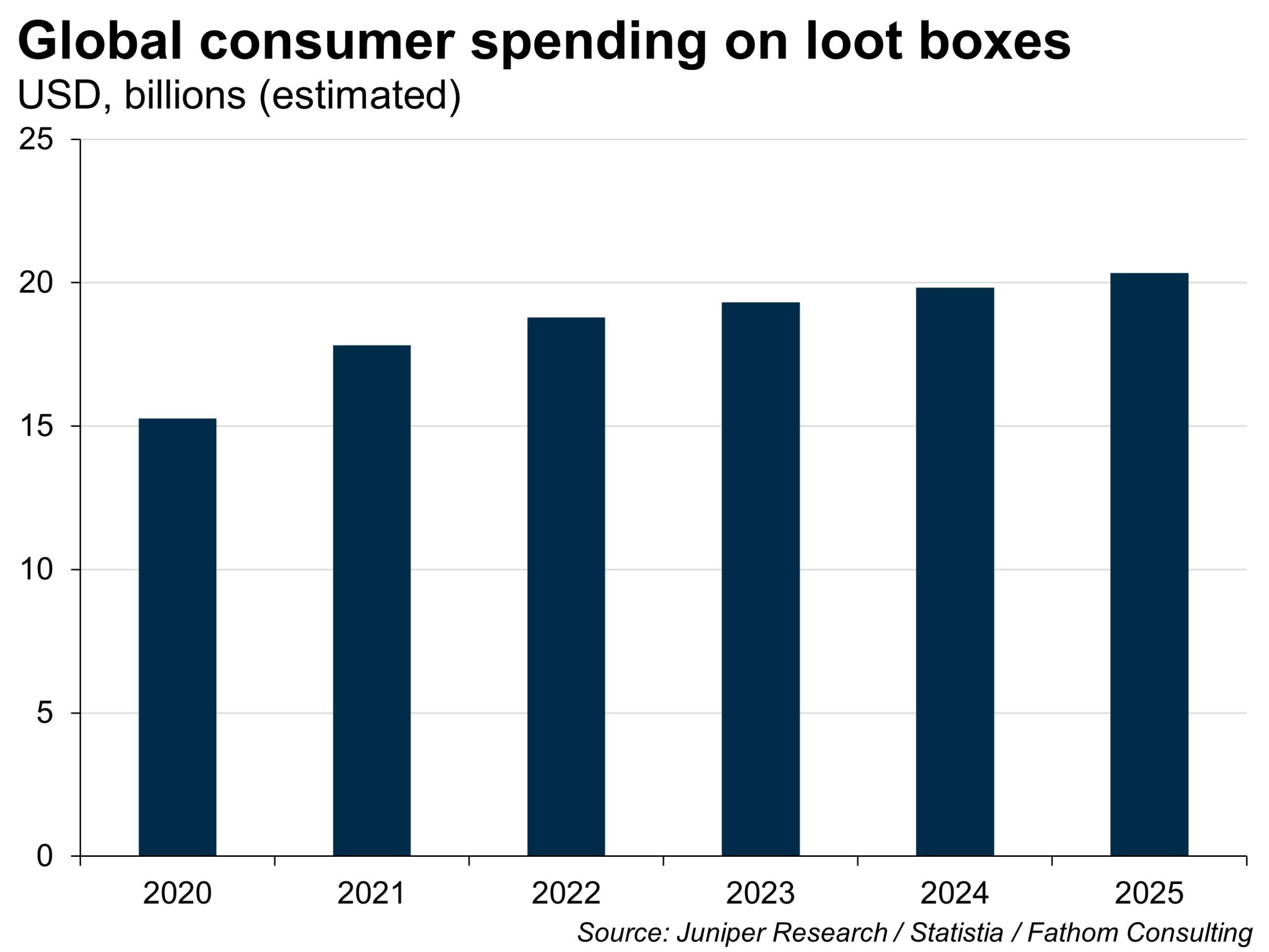

There are worse routes companies are taking to profit from regulatory loopholes. “Loot boxes” is the general term used for virtual treasure chests that can be purchased in video games, containing randomised in-game rewards. These rewards can be as simple as a different colour for items the buyer already owns. Multiple studies have linked these boxes to problem gambling behaviour, finding them to be “structurally and psychologically akin” to gambling. In 2020 they generated an estimated $15 billion, a staggering number that is expected to rise even further to $20 billion by 2025. To put that more clearly, there is a multi-billion dollar industry profiting off gambling children. While this legal loophole is moving closer to being closed (at least in the UK), technology is progressing faster than policymakers can keep up, and it is making the line between gambling and gaming less and less clear.

It’s a blurry line that needs to be brought into focus. Rising gambling rates among the young is a trend that won’t be reversed without action. Companies that knowingly profit from exploiting these unregulated loopholes should rightfully be named and shamed, but, more importantly, they should be regulated. If a child cannot wager more than £1 at a time at an arcade, then why are they able to risk an unbounded amount of money in video games? As technology becomes exponentially more complex, it is increasingly hard for policymakers to stay ahead, not just in the gaming industry but throughout the economy. Social media, for example, profits off a similar principle to gambling. While most of the content you see is dull, what keeps you scrolling is that randomness of a genuinely interesting post. Is more needed to stop this growing addiction to social media as well? Probably…

The trade-off between progress and oversight is a fair debate, now more so than ever as, from trade to technology, international competition rises. But for examples like child gambling, the answer is obvious. Not only is more oversight needed but also better education. Children need to be better equipped as they inevitably become exposed to this rapidly changing world, and not left as victims, vulnerable to these legal loopholes.

Instead of trying to chase each new technology, one option could be a principles-based regulatory framework. For example, in the gaming industry, the regulatory principle could be along the lines of ‘addictive goods and services may not be sold to children’, and could be enforced by spot checks and hefty penalties. So if you sell that kind of thing to kids, you MIGHT end up in prison. That might be enough. You can’t catch ‘em all!