A sideways look at economics

Millennials, listen up! Quit the gym, forget the morning trip to the coffee shop, cancel your Netflix subscription, and scrap your plans to go on a ‘bouji cruise’ – you might just save enough to put down a deposit on a house, according to British TV presenter Kirstie Allsopp. The Location, Location, Location host put the cat amongst the pigeons this week with her comments in a national newspaper advising young people how to get onto the property ladder. It wouldn’t be the first time under 30s have begrudgingly suffered advice from a wealthy property developer[1] whose views appear far-removed from the reality of young adults’ lives today – do you recall the avocado toast saga?

But does Allsopp have a valid point? Home ownership in the UK is starting later in life. Or, against a backdrop of post-pandemic inflation and rising housing prices, is she being disingenuous to suggest that cutting back on ‘luxuries’ will open the door to home ownership?

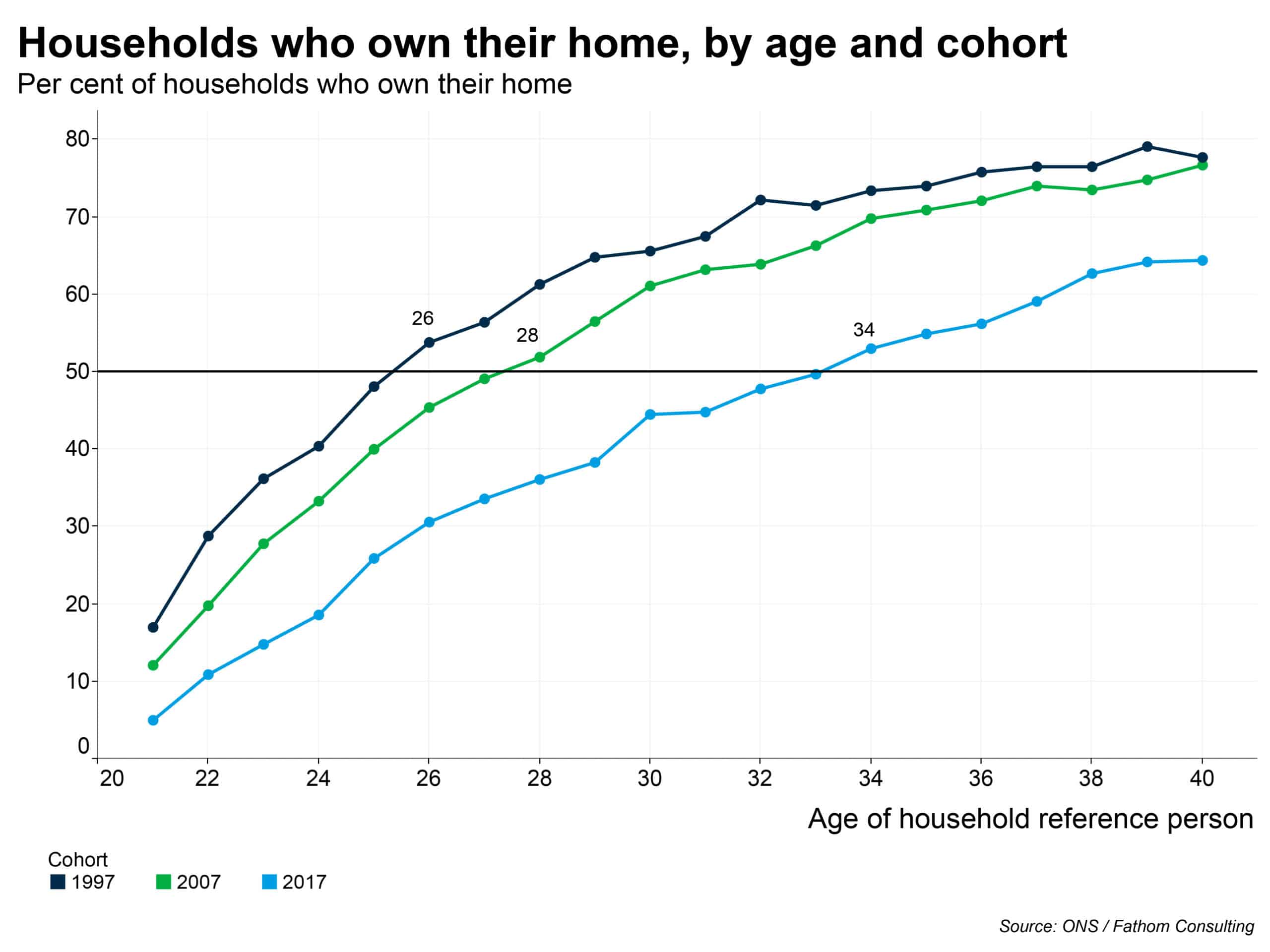

In 2019 the Office for National Statistics (ONS) published its Milestones: journeying into adulthood report, exploring how some of the modern markers of adulthood – from working life to living arrangements – had been changing in the UK over recent decades. The report identified that the age at which people owned their own home had significantly risen in the previous 20 years. In 2017 (the latest year of study) over 50% of people owned the home they lived in by the time they were 34. By contrast, the equivalent age in 1997 was just 26.

The ONS estimated that in 2017 a quarter of neighbourhoods in England and Wales were off-limits to prospective homeowners. Indeed, housing costs have become prohibitively high for young adults in recent decades. The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that the average house price has risen by 173% since 1997 after adjusting for inflation, and real incomes for young adults only by 19% across the same period.

So is Kirstie Allsopp right? Bailing on the gym (face it, you never went much anyway!), missing out on the latest season of Squid Game, and making your own instant coffee at home could save you somewhere in the region of £1130 a year.[2] Is that enough to even put a dent in the deposit required to purchase a home? Well, maybe. It might seem outlandish to suggest saving on a coffee each day means you’ll be able to afford to purchase your own home. But behind the rhetoric is a basic notion for anyone not on the bread line – and that is to live within your means. Spend less than you earn, and you will accrue savings. It’s not particularly revolutionary! But it’s an important principle.

In a book The Millionaire Next Door that a friend of mine recently gifted me for my 29th birthday, the authors Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko researched the profiles of American millionaires, seeking to understand what defines a typical high-worth individual. Surprisingly, they found that millionaires are disproportionately clustered in middle-class and blue-collar neighbourhoods rather than in white-collar regions. Moreover, millionaires tend to be unstereotypically frugal, valuing financial security over displaying high social status, and allocating their time, energy, and money to generating wealth. White-collar, high-income professionals, on the other hand, were found to be more likely to whittle away their income on luxury goods and status items, all the while neglecting savings and investments.

Budgeting, saving, and investing are all sensible steps to take towards building wealth and owning your own home. Thus, choices such as eating and drinking out regularly, or spending money on subscription services, have a very significant future value. These choices are not necessarily large financial purchases right now, but over a long period of time, the accrued opportunity cost of that money becomes very expensive. I wouldn’t go so far as to call a coffee or Netflix ‘luxuries’ of the type that the authors of The Millionaire Next Door describe, however the principle remains – if you want to save up, you have to sacrifice spending your present-day income to generate future gains.

Nonetheless, even if young adults are able to sacrifice enough income to generate significant savings, deposits for many young adults remain out of reach. The ONS finds that house prices are 6.4 times higher than incomes for 25- to 34-year-olds today, up from 3.9 in 1999. And in 2018 (latest available data) the ONS statistics indicate that typical savings would have to top £26,000 to cover up-front costs of buying the median home in England. This rises to £60,000 if you’re looking to buy in London.

Thus, some quick back of the envelope calculations reveal it would take you at least 23 years to cobble together a deposit if you saved £1130 a year not enjoying Netflix, the gym and regular coffees. And that’s 53 years if you fancy owning a home with a London postcode!

In terms of the economics, Fathom’s long-held view is that the sharp rise in the sustainable house-price-to-income ratio that took place through the early 2000s is more or less entirely a consequence of the dramatic fall in borrowing costs, and has little or nothing to do with a shortage of housing – the cost of renting a property has continued to grow broadly in line with household incomes. Owing to the fall in borrowing costs, one does not necessarily need to pay more, in real terms, to own a property over the lifetime of the mortgage even though the initial purchase price is much higher.

What creates a distortion, effectively shutting younger purchasers out of the market, is the front-end loading of costs by lenders, who — not knowing with certainty whether house prices will rise or fall over the next few years — desire to protect themselves against default. That means they tend to require a fixed proportion of the purchase price of the property to be paid by the borrower, regardless of the borrower’s income. Lower borrowing costs have pushed the sustainable house-price-to-income ratio higher, and with that the required initial deposit as a proportion of income.

The consequence of this is that any person wishing to buy property today requires far more savings up front as a proportion of their income than they did 20 years ago. A deposit on the median home for the median earner in 1999 was 33% of one’s yearly disposable income. In 2018 you’d have had to save the equivalent of 90% of your annual take home pay. Those wishing to pass life’s ‘home-owner’ milestone are consequently being asked to sacrifice far more in terms of present consumption than others before them.

In other words, Kirstie Allsopp is wrong. To suggest that young adults aren’t disciplined enough to save or should have to up sticks to other areas of the country in order to fulfil their dream of owning a home is unreasonable. Structural changes in the housing market truly have made it much harder to own property today. So, can you blame young adults who have some disposable income, for wanting to enjoy life a little when the prospect of owning a home feels so distant?

In contrast to house prices, many goods and services have become more accessible to young adults in recent decades. Clothes, TVs, and holidays are all examples of this. Indeed, a flight from London to Rome can cost less than £50. The equivalent trip made by my grandparents as young adults took days to complete, travelling on planes, trains and automobiles.[3] And in the spirit of that heartfelt, comedic movie, which portrays how people of different walks of life interact, let’s pause, empathise, and recognise that each generation faces its own economic challenges, and young adults saving on a coffee realistically isn’t going to change that.

[1] Allsop claims to be misquoted on this matter https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/kirstie-allsopp-young-people-buy-home-cut-luxuries-netflix-b981352.html

[2] Assuming you buy one £2.50 double espresso five days a week, have a £30 per month gym membership and pay for Netflix’s standard £9.99 price plan

[3] In some incredible footage my father recently had digitised, my grandmother films my grandad revving his car up a steep ramp through the nose of an aeroplane – the front of the aircraft wide open – to park his vehicle in the fuselage for their onward journey to Europe.