A sideways look at economics

A decade ago this could’ve been the sci-fi spin off from the cult classic Snakes on a Plane. Today it is reality. As the rich venture into space, should we be celebrating their achievements or be wary of the path they’re laying for our future?

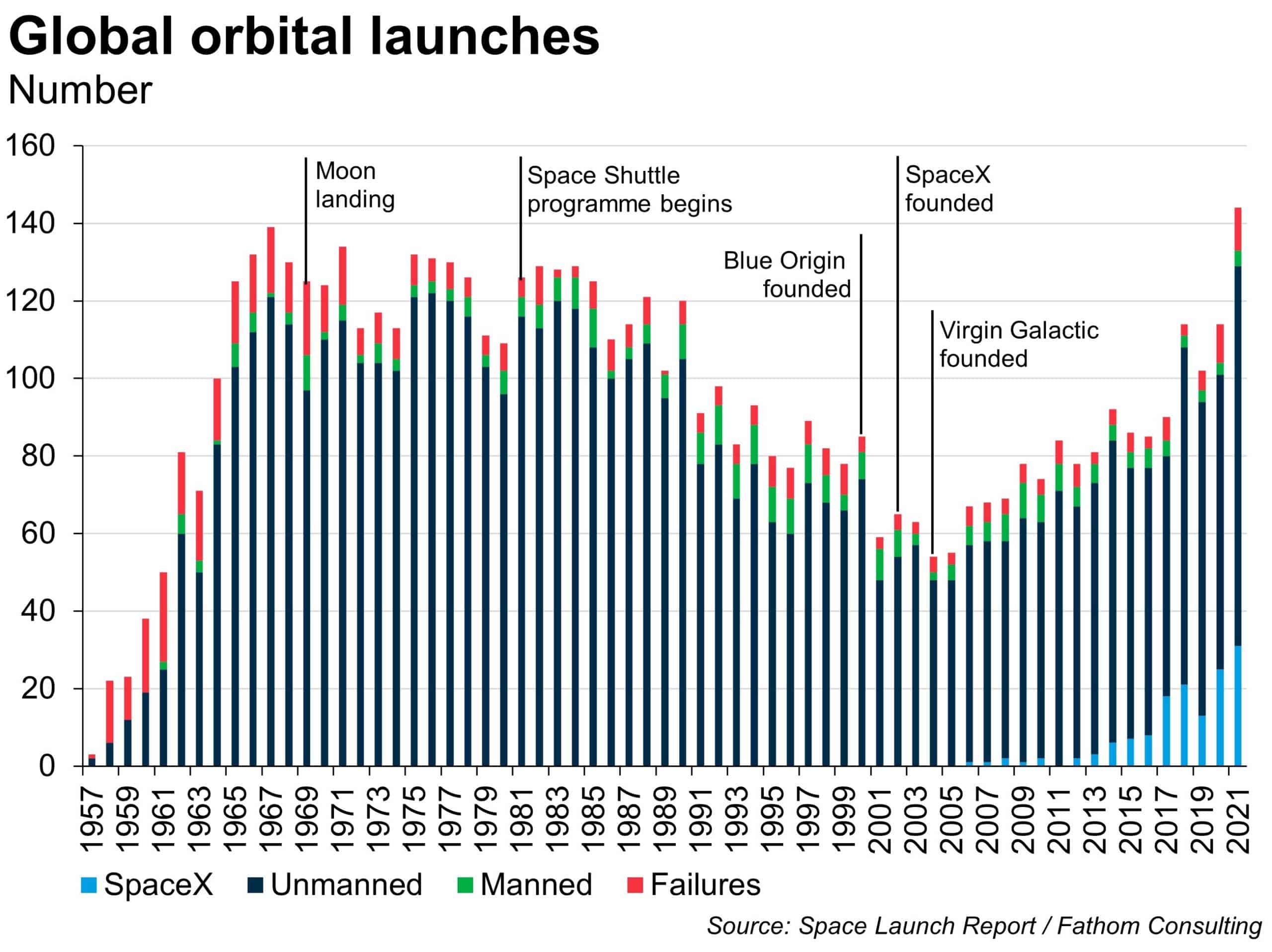

Commercial interests in space aren’t new. Private companies have been operating in the industry from the early 1960s since the launch of the satellite Telstar 1, which enabled the first live broadcasts between the US and Europe. Unfortunately, after only seven months, it was “accidentally” taken out by a high-altitude US nuclear warhead (I guess they weren’t fans of European TV). But only recently has the private sector developed space systems competitive enough to break the public sector’s monopoly. SpaceX was established 20 years ago. In that time they’ve launched both satellites and humans into orbit while also developing both the world’s first reusable rocket and the most powerful rocket in history. After a steady decline in interest in space exploration since the moon landings, private companies have undoubtedly reignited humanity’s ambition to explore the final frontier. In 2021, SpaceX accounted for roughly 20% of all orbital launches globally, and 70% of those from the US alone. (Other space companies are available, although there’s only so much time I can justify spent trawling through launch logs…)

Tourism, space stations, lunar landings and even Martian colonies, the range of projects currently under way by private companies is rapidly increasing. It may look like NASA is on the verge of becoming redundant. In reality, however, most major US projects are now contracted and largely funded by NASA. The change from doing things in-house was driven by a need to cost effectively fill the gaps left by the end of the space shuttle programme in 2011. The involvement of the private sector has since expanded to cover most projects. Take the International Space Station, for example, which is to be decommissioned within the next decade. Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin is one of several companies currently competing for the NASA contract to replace it. The ISS’s replacement will feature commercial activities as well as scientific ones, a telling sign of the change in recent years.

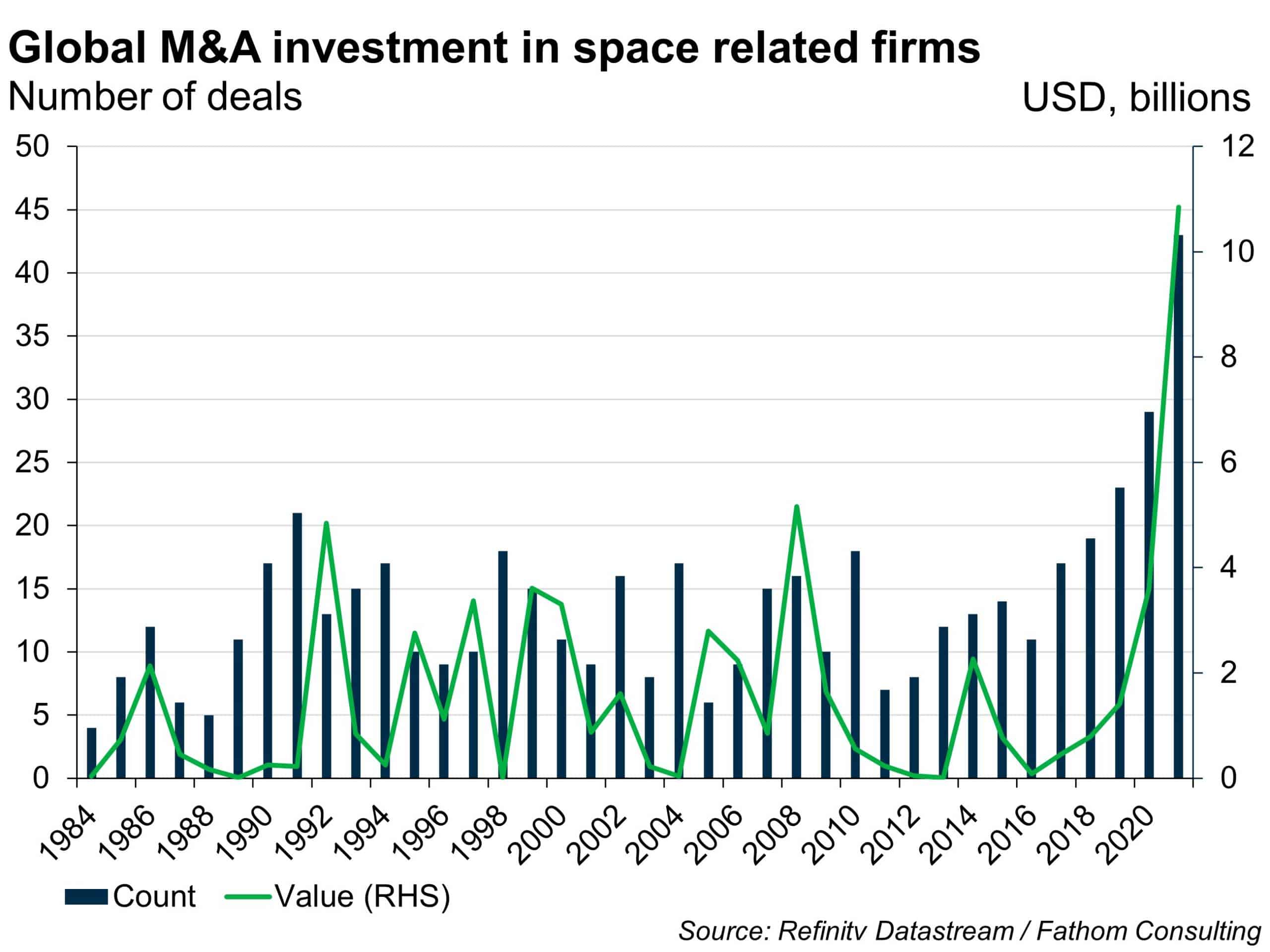

Competition is a key driver of innovation. As innovation has grown so too has the industry’s potential for profit, and the result has been a wave of investment into the sector. How much longer will companies be financially dependent on NASA’s funding? The answer is probably not long. Elon Musk’s plans to land on Mars are, as yet, not funded by NASA. Some even see the company competing with NASA on missions to the red planet, particularly over how future colonies may look. Currently regulation in the industry is light, aiming to “foster the conditions for… economic growth and technological advancement”. As the private sector grows more independent from NASA’s funding and guidance it’s likely regulation will be tightened. On the other hand, the main players in this sector have a lot of money to spend on lobbying…

So, it’s undeniable that privatisation is here to stay; but what are the costs of this explosion in space exploration led by the uber-rich?

Most obvious, perhaps, is the environmental cost. Shooting thousands of tonnes of equipment into orbit is hardly going to aid the global fight against climate change. Most rockets use carbon-based fuels, such as kerosene. Falcon-9 rockets, SpaceX’s flagship, produce around 340 tonnes of CO2 emissions on launch, equivalent to roughly 400 transatlantic flights. What’s worse is that these emissions are deposited directly into the upper atmosphere, causing their effects to linger longer than those emitted on the ground. Currently these launches represent a negligible fraction of global emissions, but the industry is growing fast.

However, there are viable alternatives. Blue Origin’s BE-3 rockets use a mixture of liquid hydrogen and oxygen which produces almost entirely water vapour and no CO2. Whilst this is a significant improvement on carbon-based fuel, in the upper atmosphere even water vapour is damaging to the climate. There is also hope that advancements in satellites and other space tech can be used to better monitor and understand climate change globally, which in turn would lead to more informed decisions. In fact, this week satellites were used for the first time to map large leaks in methane gas, a major contributor to global warming.

Aside from the environmental impact of rocket launches, there are also moral dilemmas resulting from these scientific leaps. Rather oddly, one of the more interesting debates has been triggered by one app’s terms of service. Who even reads those things? The Starlink app, which uses SpaceX satellites to provide high speed internet, noted in its terms of service that whilst operations on Earth and the Moon would adhere to the laws of the State of California:

“For Services provided on Mars, or in transit to Mars via Starship or other colonization spacecraft, the parties recognize Mars as a free planet and that no Earth-based government has authority or sovereignty over Martian activities. Accordingly, Disputes will be settled through self-governing principles, established in good faith, at the time of Martian settlement.”

The Outer Space Treaty, of which most of the world including the US is a signatory, declares that outer space is not subject to national sovereignty by any means including non-governmental entities. But this treaty was signed before humans even stepped on the moon; how enforceable will treaties like this be now we are on the cusp of extra-terrestrial colonies? I for one think it would be very entertaining taking a trip to a nation state run by the Dogefather himself…

In all seriousness, though, whether it’s colonies on Mars or ones in orbit (which seem to be the focus of Blue Origin), we should question whether the leaders of this new space age are the leaders we want setting the precedent for our future outside Earth. Whilst making their billions, there have been criticisms of the working conditions in the companies run by both Musk and Bezos. In some years, they have also got away with paying zero income tax. This may have helped to enable these space ventures. Would it really be a proud moment for our species to build new civilisations under these premises? Maybe I’m getting ahead of myself. Civilisations run by billionaires are just a far-off dream confined to science fiction. Then again, at some point the same was said about landing on Mars…