A sideways look at economics

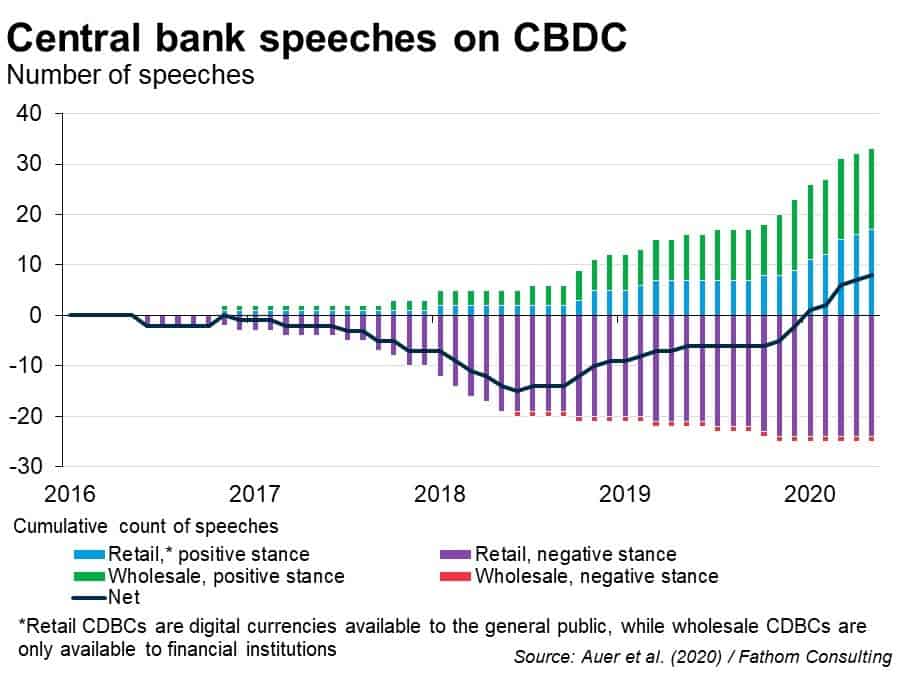

Many of us have embraced digital technologies during the pandemic, increasing the amount of our shopping done online and keeping in touch with colleagues, friends and family through videoconferencing. The trend of digitalisation is also increasingly rippling through the staid world of central banking. Central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) have soared towards the top of the agenda recently, generating an increasing volume of chatter among central bankers in an ever-more excited and positive tone. Federal Reserve Chair Jay Powell has announced that a discussion paper on the benefits and risks will be published in the summer, while the European Central Bank (ECB) announced the launch of the digital euro project this week, with an investigation phase beginning in October and lasting around two years.

While there are plenty of motives for looking at a CBDC right now, not least the threat posed by cryptocurrencies to central bankers’ previously unchallenged control of the money supply, one of the key drivers for the Fed and perhaps the ECB appears to be the imminent arrival of a Chinese digital renminbi (RMB). A fear is that it will displace the US dollar as the world’s major reserve currency and presumably push the euro further down the pecking order.

The extent of official nervousness that China may be stealing another march on the US is shown in the number of times Chair Powell and other officials have been asked about this possibility in congressional testimony. Similar anxieties have surfaced in Europe, where the Banque de France Governor recently suggested that a digital RMB poses a key risk to the euro’s international role. Some fear that the US and EU have been too slow off the mark, and China will enjoy significant first mover advantages, although Powell has seemed less concerned about this.

So, what exactly is the digital RMB? China has been exploring a CBDC, called Digital Currency/Electronic Payment (DC/EP), since 2014 and began running pilot schemes in several cities from last year. Ten million people have now signed up to lists to receive the digital RMB through state-owned banks, and the next major trial is set for the Beijing Winter Olympics.[1] In some of the pilots, digital money was distributed in virtual red packets to those chosen via lotteries, similar to the tradition of giving red envelopes to family members at Chinese New Year. It seems highly likely that we will see a full rollout of the digital RMB in the next few years.

Like all prospective CBDCs, it will be an electronic form of money similar to commercial bank deposits, although it will have the full backing of the central bank. Given the country’s huge population and policymakers’ desire not to disintermediate the financial system, individuals will not hold accounts directly with the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), but will instead hold digital RMB in digital wallets at commercial banks and other financial institutions. The authorities see it as a substitute for cash and no interest will be paid on holdings. An interesting design feature will be ‘controlled anonymity’, which means that lower value transactions will enjoy some level of anonymity — including from the e-commerce providers.[2],[3]

Policymakers have highlighted several motives for China issuing a CBDC. These include the desire to safeguard monetary policy sovereignty and capital account control from the threats posed by cryptocurrencies. A digital currency controlled by the central bank also offers a backup to the heavily concentrated retail payments system, amid Alipay and WeChat Pay’s dominance in mobile payments. It can also be a way of improving financial inclusion.[4] At present the DC/EP is mainly intended as a domestic tool, though there are hints that this may change in future as the PBoC recently joined a BIS-led cross-border payments project with other central banks[5]. Longer term aims of the government are likely to include reducing dependence on the USD-based financial system and exposure to potential US sanctions.

So, will the digital RMB be a game changer? From a domestic standpoint, some observers suggest that the biggest impact will be on technology payments firms, redressing the balance of power between them and the banks. This is because under controlled anonymity, neither the banks nor the technology companies will be able to see the data behind customer transactions, removing a major advantage of the of the latter’s business model. Wei (2021) also suggests that the PBoC could decide to provide such data to the banks.[6] The recent treatment of Jack Ma highlighted where the real power lies in China!

The digital RMB is also likely to be useful crisis-fighting tool, allowing the PBoC to send money directly to individuals. And by hastening the demise of cash, a digital currency could make it easier for the central bank to implement negative interest rates in the future, while having the added benefit of putting a spoke in the wheel of drug dealers, corrupt politicians and business leaders, and other criminals who operate on a cash basis.

To the many, interested, international observers, however, the key question is whether China’s digital currency project will propel the renminbi to global reserve currency status. Could it replace the USD as the preeminent reserve currency? Despite the nervousness, the simple answer is no – or at least, not just yet. Despite representing almost one-fifth of global manufacturing exports and being included in the IMF’s Special Drawing Rights Basket since 2016, the RMB has made little progress to reserve currency status. Indeed, as the chart below shows, it is still languishing behind sterling as a vehicle for payments and FX reserves.

Realistically, a digital currency is unlikely to be a “magic bullet” that will change this. Indeed, the USD’s reserve currency status derives from a number of social and political as well as economic factors, such as America’s globally respected institutions, which include a political system with checks and balances and an independent judiciary and central bank, on top of its open capital account, and its high-quality, deep and liquid asset markets. China does not have these, and a digital currency would not suddenly change this. What’s more, there is no evidence that the digital RMB will have superior attributes to existing domestic and international payments systems that would lead to it taking off in an explosive way.[7]

All in all, it seems unlikely that the digital RMB will be a major game changer for the global economy over the short to medium-term, although its imminent arrival appears to have helped to spur some other central banks into action. Debates will continue on the costs, benefits and potential risks associated with CBDCs and I will be a very keen observer. I am also hoping that I will make it onto the list of those receiving a digital ‘red packet’ from the Bank of England if it begins trialling a digital pound — or perhaps more likely a red, white and blue packet!

Read more from Fathom on cryptocurrencies:

‘A tale of two cryptos‘

[1] China digital currency: Beijing Winter Olympics next key trial as pilot programme expands to 10 million | South China Morning Post (scmp.com)

[2] Some thoughts on CBDC operations in China – Central Banking

[3] Are there data and privacy protection concerns? | South China Morning Post (scmp.com)

[4] BIS Innovation Summit 2021: How can central banks innovate in the digital age?, Fireside Keynote – Featuring Mr. Mu Changchun of the People’s Bank of China | Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy (umich.edu)

[5] Press release: Central banks of China and United Arab Emirates join digital currency project for cross-border payments (bis.org)

[6] How Will the Digital Renminbi Change China? by Shang-Jin Wei – Project Syndicate (project-syndicate.org)