A sideways look at economics

“You’re indestructible

Always believing

‘Cause you are gold!”

From Gold by Spandau Ballet, 1983

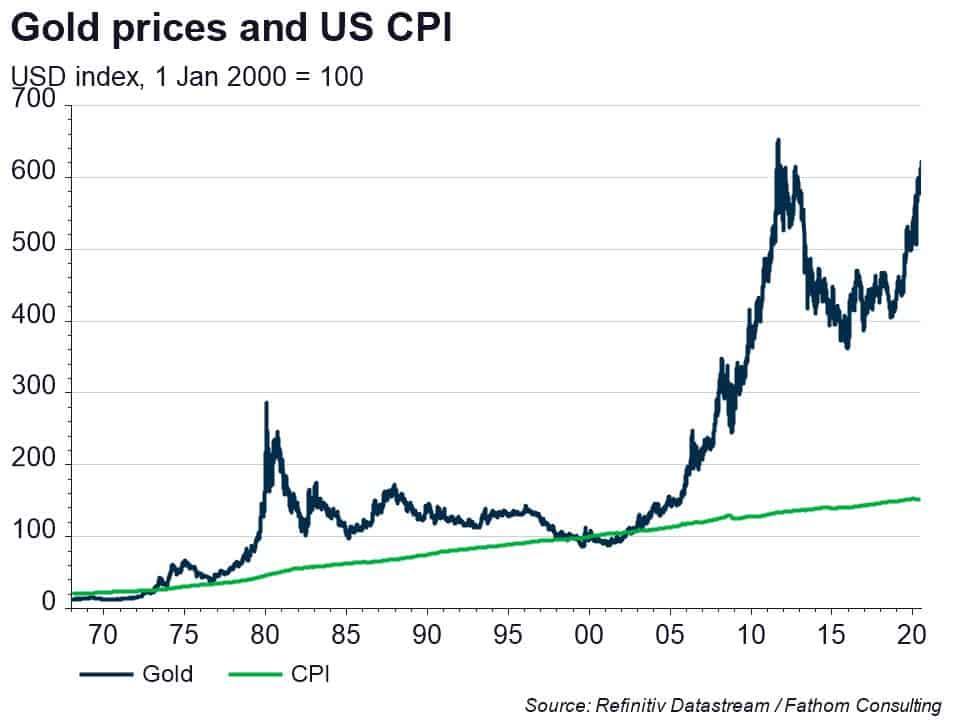

Over the past 20 years or so, the US dollar price of an ounce of gold has risen six-fold, far outstripping the increase in the US CPI. Why is gold so expensive?

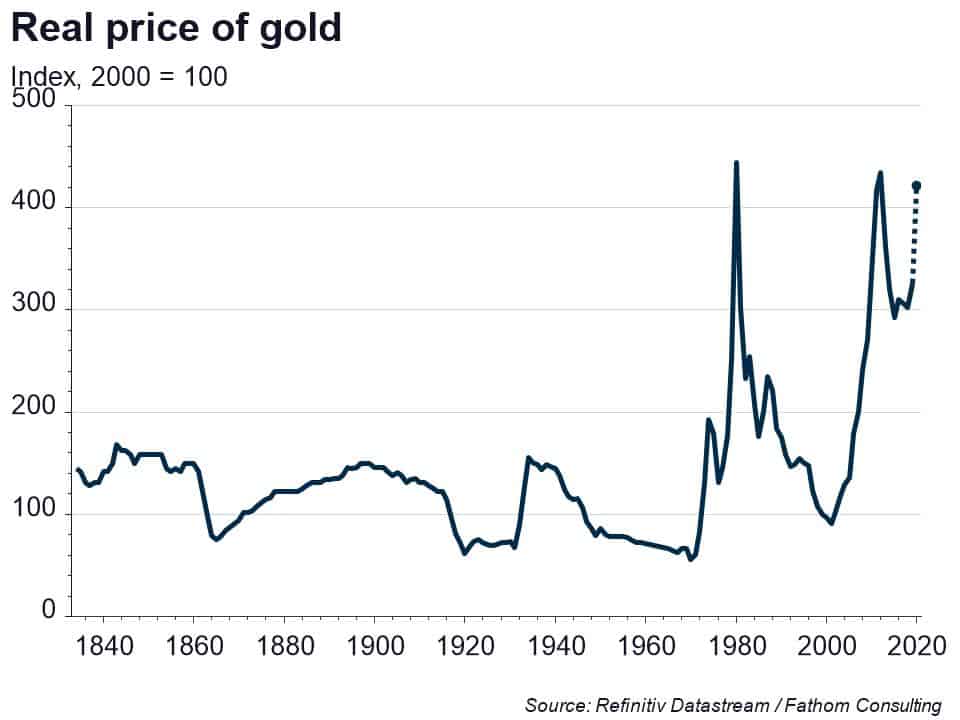

If the market for gold extraction were competitive then, much like any other commodity, its price would gravitate towards the marginal cost of extraction. And if the marginal cost of extraction were to rise in line with the general price level, then the real price of gold would be stationary.[1] These are two very big ‘ifs’, nevertheless, by eye at least, there is some evidence for mean reversion.[2]

But how can we account for the two big spikes in the real price of gold, one starting in the early 1970s, and one in the early 2000s? It must be a question of demand and supply. On the demand side, gold looks nice. That’s one reason people like to hold gold, principally in the form of jewellery. It also has properties that benefit the electronics industry. So, there is a ‘use’ demand for gold. But there’s also an ‘asset’ demand. As Spandau Ballet remind us, as well as looking nice, gold is (more or less) indestructible. This has made it attractive as a medium of exchange, and as a store of value, for close to 3000 years. Modern portfolio theory suggests that the value of gold as an asset will depend on beliefs about the distribution of the likely returns to gold, and about the distribution of the likely returns to all other assets. With the use demand for gold relatively stable and predictable, and with supply slow to respond to changes in demand, I would assert that it is shifts in the asset demand for gold that have driven big fluctuations in its price, relative to the prices of other goods and services.

For most of the period since its introduction in the late 1700s, the US dollar has been convertible into gold at an exchange rate that was fixed, often for decades at a time. During the long period of convertibility, gold and cash were close substitutes. Neither paid interest, yet both facilitated transactions, and acted as a store of value.[3] In this world the quantity of gold, the quantity of US dollars, and the US price level all moved closely together.

Convertibility of the US dollar came to an end under President Nixon in August 1971. From this point on, although the supply of gold remained, to a degree, knowable, the supply of US dollars became a choice variable of US policymakers, making it hard if not impossible to predict. From August 1971, gold suddenly became far more attractive than cash as a store of value. The asset demand for gold rose sharply, driving its price higher relative to the prices of other goods and services. The first spike in the real price of gold, I would assert, was driven by inflation uncertainty in a world of fiat money. Inflation did indeed rise sharply, shortly after the period of convertibility came to an end. But eventually inflation was brought back under control, in part through the use of inflation targets, and by the late 1990s the real price of gold had returned to its historic average.

How, then, do we account for the second spike? Gold bugs would argue that fears about currency debasement have again come to the fore, with high levels of government debt giving policymakers the incentive to create higher inflation.[4] That incentive is undoubtedly there, and yet inflation expectations remain well anchored, and close to target. If fears about currency debasement are what has driven the real price of gold higher since the early 2000s, gold investors must have a very different set of beliefs to those trading in US TIPs, or US inflation swaps.

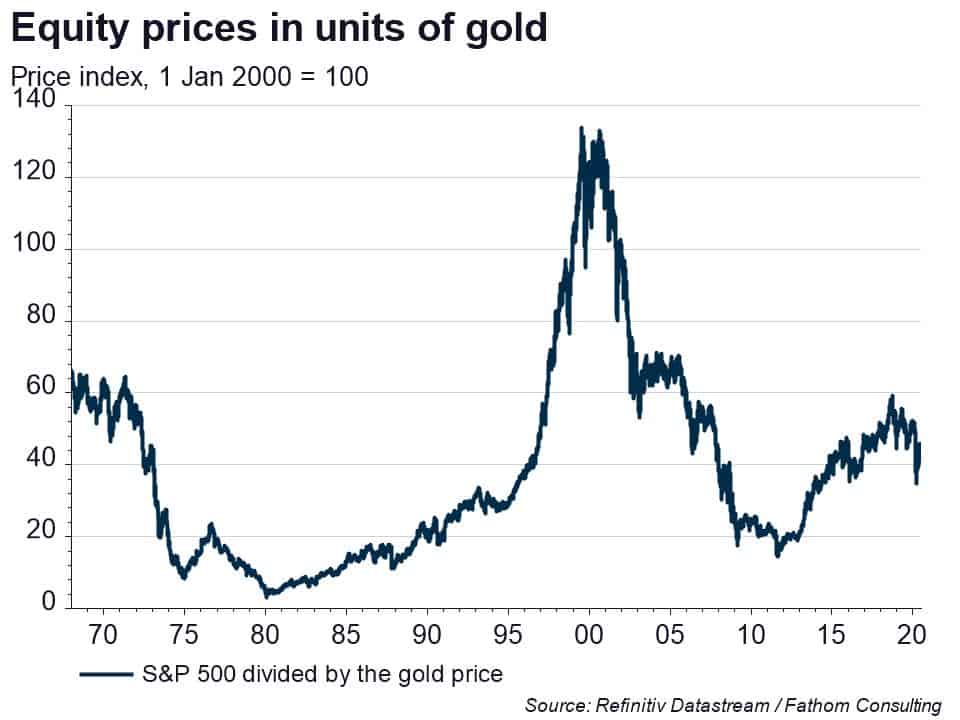

A more plausible explanation for the surge in the real price of gold since the turn of the century is, in my view, the steady decline in the real risk-free rate of interest. The disadvantage of holding gold as an asset has always been that it offers you no income. But after adjusting for inflation, very little does in this world of high debt, low interest rates and low growth. The fall in the real-risk free rate, aided by QE, has driven all asset prices higher in real terms — equities, bonds and gold. The final chart in this week’s blog is another favourite of mine. If we measure equity prices not in US dollars but in units of gold, the equity market rally from the depths of early 2009 looks less impressive, while the dot-com bubble looks even larger still.

So, what’s the outlook for gold prices? I don’t know! Over very long periods of time, the real price of gold appears to mean revert. That would suggest a price of around $450 per troy ounce at today’s general price level, rather than the $1800 per troy ounce that we have seen in the market this week. But mean reversion is slow. On average it takes close to five years for the real gold price to move just halfway back to its long-term average. And if a slower-than-expected recovery from the economic consequences of COVID-19 pushes government debt higher and real yields lower, while causing some to worry even more about currency debasement, it may yet rise (much) further from here.

[1] One of my favourite charts shows that since the 1860s, and measured in today’s prices, a barrel of oil has usually cost around $20, except for three relatively short periods of 15 years or so where it has cost far more.

[2] Strictly, using more formal statistical tests, we would just fail to reject at the 10% level the null hypothesis that the real price of gold is stationary. Nevertheless, other researchers have argued that these tests have relatively low power and concluded that it probably is.

[3] One might argue that, by looking nice, gold does afford the user a flow of services that act as a form of interest. However, those holding gold as an asset tend to lock it away somewhere safe, and so fail to enjoy those benefits.

[4] Others still might suggest that it is fears about currency debasement that have made BitCoin so attractive. The difficulty with this argument is that, although the supply of BitCoin itself is finite, the supply of crypto-currencies in general is infinite — you can always invent a new one. Gold has been accepted as a medium of exchange for close to three millennia; BitCoin not so long.