A sideways look at economics

My earliest memory of anything remotely related to economics was the financial crisis of 2008. I came home from school to find my dad keenly watching the news. The stock market had crashed, he told eleven-year-old me. I changed out of my uniform, ate a sandwich, and went to play cricket with my friends.

A few years later, when I first started studying economics, the fallout from the crisis dominated the macro debate. It was all I was interested in. I learnt about asset bubbles, the credit crunch, confidence crises, and productivity. I also studied monetary policy, both ‘conventional’ and ‘unconventional’. The distinction between them was straightforward. Changing interest rates was conventional, and everything else was not.

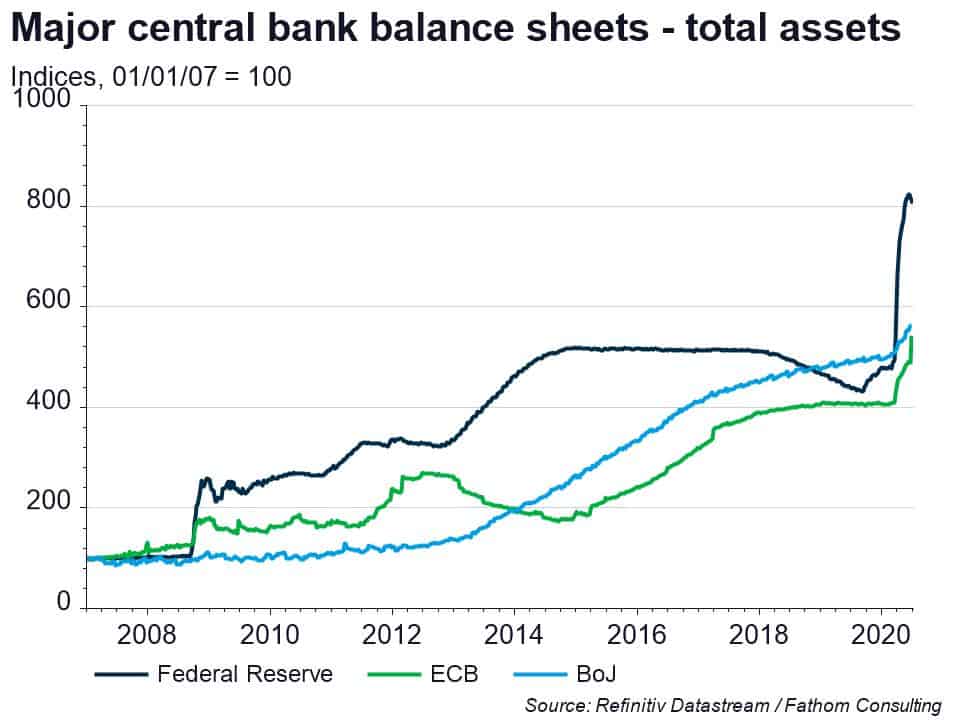

Now twelve years on from that crisis, in the midst of another one, the ‘unconventional’ policies have returned, and some had never left. Although the Federal Reserve ended QE in 2014, the ECB restarted its programme within a year of winding it down, and the Bank of Japan has been doing it since the early 2000s. The latest round of asset purchases announced to deal with the COVID-19 recession are likely to be five-to-ten-year programmes themselves, and are almost certain to be the main element of monetary policy for the next crisis, barring the unlikely case that we return to interest rates of the mid-2000s. So, can we now call QE conventional? Well, there are two main characteristics of something conventional: being broadly accepted; and being in place over a long period of time. QE is certainly set to stay for advanced economies, but it no longer appears to be exclusive to them. Emerging markets such as Indonesia, Chile, and Turkey to name a few, have launched QE programmes despite being significantly above the effective lower bound for interest rates.

Of course, QE is not the only unconventional policy that has become a permanent addition to the toolkit. According to the Fed’s website, it has conducted explicit forward guidance in all but two years since 2008, and is likely to do so again this year. Though negative interest rates are still truly ‘unconventional’, they are much closer to the middle of the spectrum than they once were. The Zero Lower Bound is now a myth, yet over the course of two degrees I have learnt more about it than either forward guidance or QE. Two of the Big Four central banks (ECB and BoJ) have interest rates in negative territory, and the Bank of England appears to be seriously considering it.

But does it really matter whether they are called conventional or unconventional? To me, this is more than just semantics. For the last few years, many have warned about the lack of ammunition held by central banks in developed markets which they can use to combat a recession. There was no space for substantial rate cuts. Yet, few would argue that the responses of central banks thus far have not been enough. There have been some innovative measures — by buying corporate debt the Fed has ensured that liquidity remains in target markets, and in doing so has started to expand the definition of a safe asset. Central banks have also been using macroprudential tools, such as reducing capital requirements, to keep credit flowing through their economies.

Still seeing QE and forward guidance as unconventional and innovative will only hamper further policy innovation. Like any other discipline, economics must evolve. Central banks have successfully restored calm to financial markets, but will this be enough to translate into positive macro outcomes? Will it bring inflation back to target? Inflation, at target? Now, that would be an unconventional idea!