A sideways look at economics

Our hands have probably never been cleaner. The spread of the novel coronavirus over the past couple of months has led to nothing short of a ‘run’ on hand sanitiser, as seen by early morning queues outside your local Superdrug. A number of interesting economic phenomena can be observed from market pricing, consumer stockpiling, and the government’s response.

In markets with more flexible price structures such as Amazon, an increase in the price of hand sanitiser reflects a sudden shift to the right of the demand curve. As consumers want more of a fixed amount of goods, they are willing to pay a higher price. Furthermore, ‘price gouging’, i.e, unreasonable increases in prices by sellers, reflects the sellers’ assumption that not only has the demand curve shifted to the right, but that it has also become highly inelastic in the short term. A large increase in price will not deter consumers from buying.

Stockpiling itself is akin to a bank run. Bank runs occur when a sudden increase in the demand for cash by depositors (often a perceived bank-solvency crisis) leads to a liquidity crisis, which may then cause an actual solvency crisis itself. If depositors believe that their money is at risk, they will attempt to withdraw it. If the share of depositors with such a belief is large enough, banks may not have sufficient liquid funds available, and are therefore forced to liquidate long-term assets, potentially at a loss, weakening their balance sheet. This adds to the perception that the bank is on the verge of collapse, encouraging more depositors to try and withdraw their funds. The cycle goes on until the bank collapses.

Similarly, with hand sanitiser, a sudden increase in demand by a large enough share of consumers means that supermarkets don’t have enough product to meet people’s needs. Consistently empty shelves add to the belief that hand sanitiser is going to be in short supply over the coming months, encouraging other people to also begin stockpiling the product. Some consumers, particularly those unable to deal with the physical strains of queueing up outside the pharmacy and sprinting to the sanitiser aisle, won’t be able to buy it and will therefore be more susceptible to contracting COVID-19. Of course, the more people with COVID-19 around us, the more likely we are to contract it ourselves. In both the case of the bank run and the run on hand sanitiser, the game theory is the same — the Nash equilibrium is destructive, and a coordinated strategy would lead to a superior outcome.

What about government responses? Though governments across the world have employed different policies such as lockdowns, travel bans, and even state production of hand sanitiser, the policy I’m going to focus on is export bans of medical products. As part of an ongoing major consultancy project, Fathom has created a detailed database of global trade using narrowly defined product classifications. We assign our own categories to over 5000 Harmonized System (HS) codes, allowing us to uncover links between countries that would otherwise be overlooked.[1] While hand sanitiser doesn’t have its own code, the US Customs and Border Protection agency suggests they fall under HS code 382499, which I will use as a broader proxy for hand sanitiser.[2]

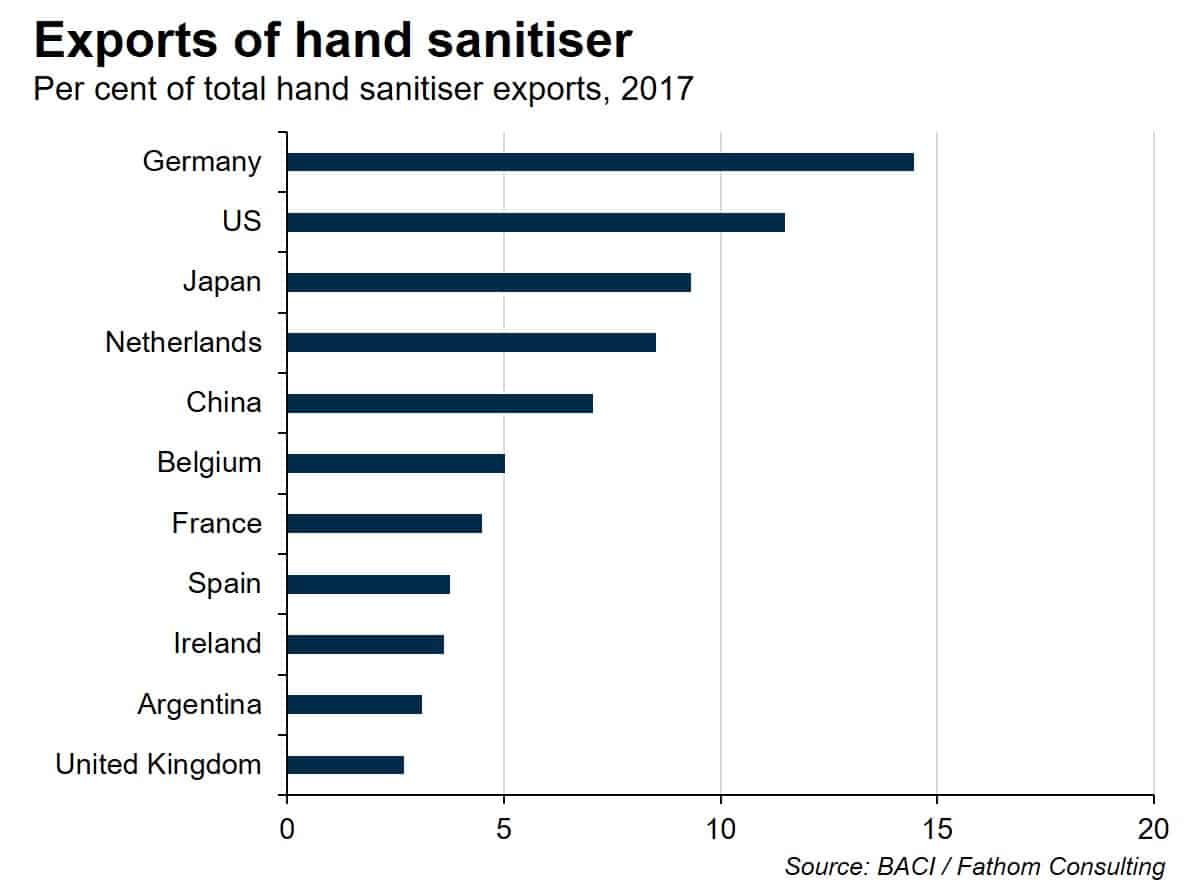

The chart below shows the global market shares of the eleven largest exporters. Of these, Germany and France have already imposed restrictions on the export of protective equipment such as masks and other protective equipment, and other EU countries are contemplating following suit. By limiting the amount sent abroad, governments are hoping to increase the volume available to domestic markets, thereby reducing the chronic shortage. It’s not unreasonable to think these restrictions will eventually, if they have not already, be extended to include hand sanitiser.

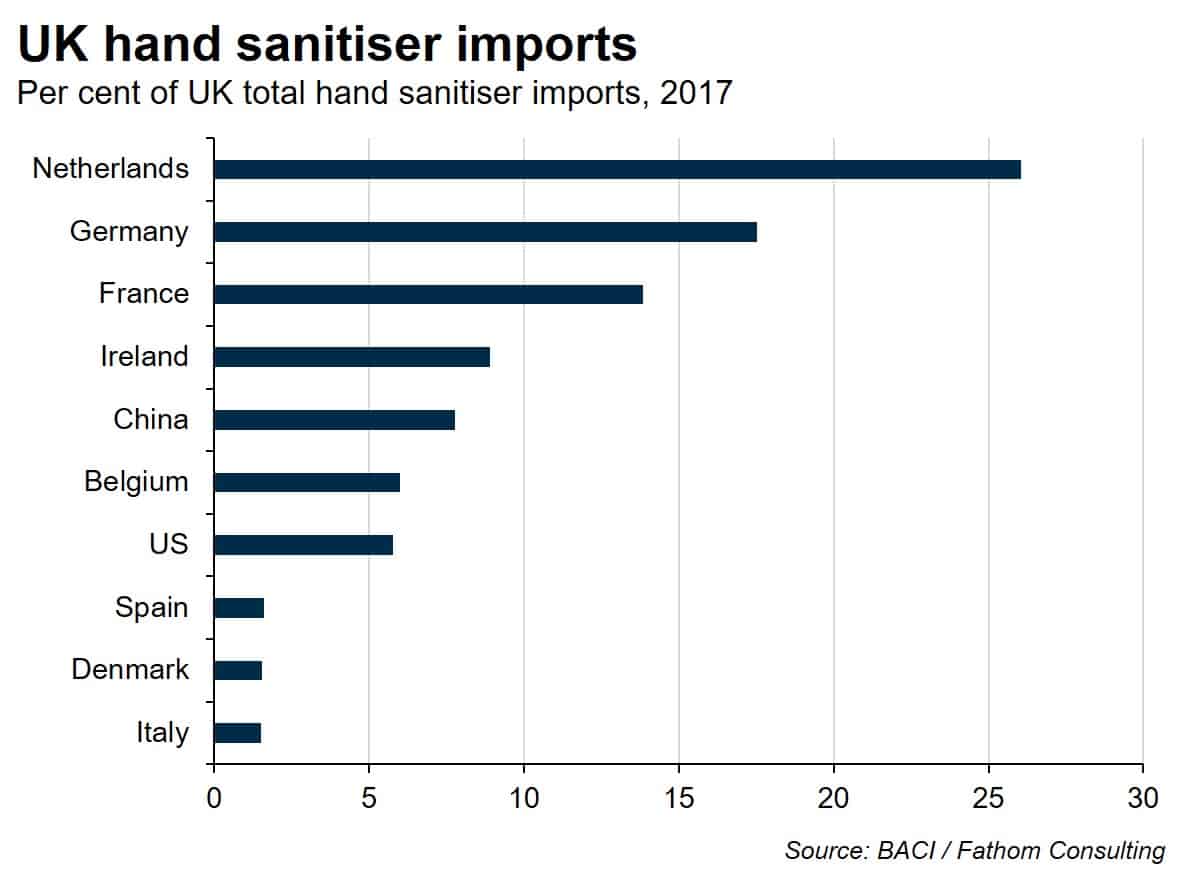

Here in the UK, our Top 3 sources of ‘hand sanitiser’ are all in the EU, and account for over 50% of imports. Importing the product into the UK may not be inhibited by Brexit, as the transition agreement remains in place, but by self-imposed export restrictions.

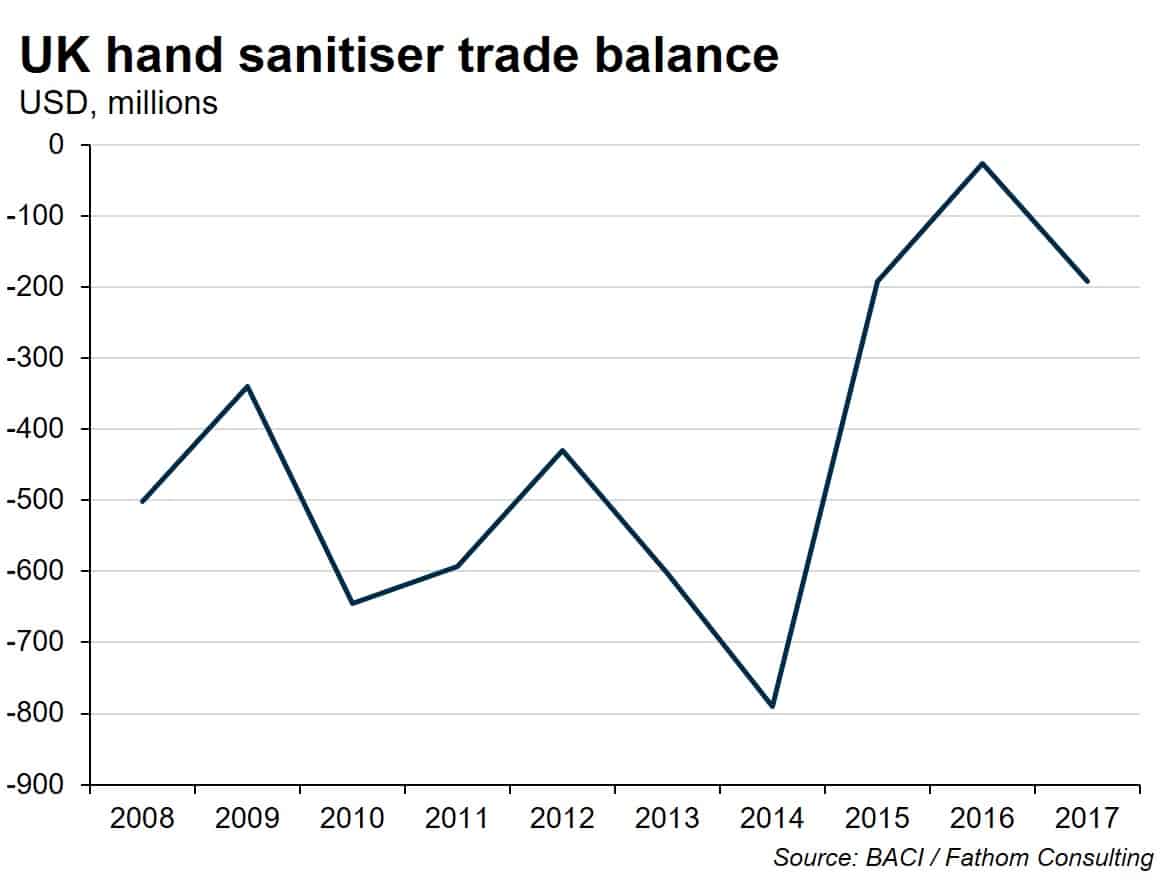

It may be, however, that we are more self-reliant when it comes to hand sanitiser than we were before. As the world’s 11th largest exporter of the coronavirus-slayer, imposing our own export restrictions could help, should we be cut off by our European neighbours. The UK is still a net importer of hand sanitiser, and though things have improved — the trade deficit in ‘hand sanitiser’ has fallen from $800m in 2014 to $192m in 2017 — we would be left short of the product if all trade ground to a halt.

Nigeria is taking a longer-term view. The country has yet to experience infection on the scale of Asia or Europe, but has bizarrely restricted imports of hand sanitiser, in order to prop up domestic production. The biggest loser from this policy, both in relative and absolute terms, would be South Africa, which sent 42% of its ‘hand sanitiser’ exports to Nigeria in 2017.

Ultimately however, hand sanitiser is just one of the numerous ways to reduce the likelihood of catching COVID-19. The craze surrounding it is driven partly, if not largely, by what behavioural economists call ‘herd behaviour’, i.e making decisions based on the actions of others as opposed to basing them on one’s own sense of utility. The World Health Organization’s advice is to use either ordinary soap and water or hand sanitiser, both being effective at reducing virus transmission. However you choose do it, wash your hands folks.

[1] To find out more about this work, get in touch at enquiries@fathom-consulting.com

[2] https://www.customsmobile.com/rulings/docview?doc_id=NY%20N303248&highlight=3824.99.92%2A