A sideways look at economics

“One more episode and then I’ll go to sleep” — we’ve all been there. You watch the next episode, it ends on a cruelly suspenseful cliffhanger and before you know it it’s 3am and coffee is your only means of surviving the following day at work. Streaming of TV shows and movies has become a global phenomenon, and for the first time, in 2018, became the most used medium for viewing content, according to a recent report from PwC. Netflix has forged a blazing path in what a few years ago was a relatively new, unknown market, but is now a flourishing industry with significant financial rewards. With the release of Apple TV+, Disney+ and the slew of streaming services set to follow throughout 2020, it’s worth considering how their potential success reflects on us and our behaviour as consumers.

With the advent of streaming and its exhaustive library of content, the days of searching through your seemingly endless back catalogue of DVDs are over; tell Netflix what you want and the chances are you’re a button-press away from the opening credits — which you can also skip to save even more time (don’t tell Steven Spielberg). You have convenient and immediate autonomy over your viewing schedule — why set foot in HMV ever again? It’s hard to justify leaving the app, let alone the comfort of your living room.

So how has Netflix in particular achieved such a meteoric rise? Netflix thrives on the premise that their monthly subscription represents exceptional value for money. They can accept lower subscription revenues in the short run and bide their time, letting consumers get hooked, before leveraging their established position by raising prices when viewers have found shows they can’t live without. Induce price-inelastic demand and gradually increase the price consumers are willing to pay, while in the process also muscling out rival firms that can’t afford to price so aggressively. This approach also generates notions of Netflix being an unmissable, members-only brand; they use lower subscription fees to build a sizeable customer base, and watch the subsequent buzz about their offering escalate to such an extent that the fear of missing out is just too great.

Additionally, a fundamental assumption of conventional microeconomic theory is that consumers prefer consumption today compared to deferring to the future. We’d only delay watching the next episode of our favourite show if there was an incentive to do so. No such incentive exists, and the only cost to the consumer, speaking from experience, is the gaping hole left in their life for another year after binge watching the new series of their favourite show in one energy-drink-fuelled sitting.

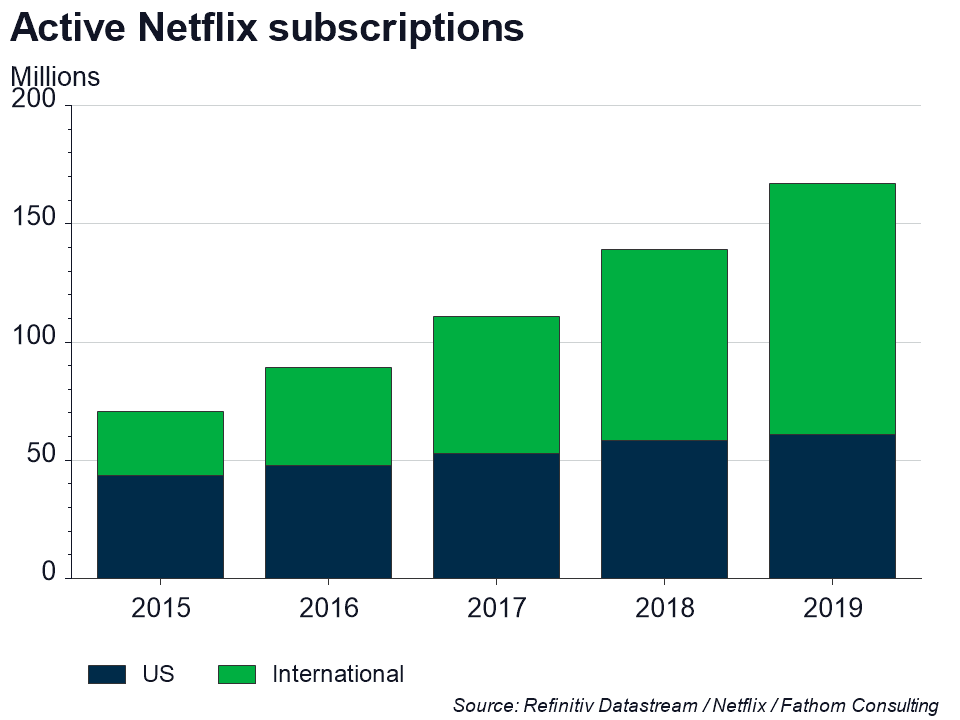

This instant and flexible gratification only enhances the aforementioned attachment or buzz Netflix is able to induce and is an approach that traditional viewing methods can’t rival, the numbers proving pretty damning for TV and cinema purists. According to Netflix, the latest series of global hit Stranger Things was streamed by 64 million people, the highest streaming figures in the platform’s history (don’t worry — I cried at the heart-wrenching conclusion to the latest series too). Meanwhile, the BBC’s most viewed drama since 2008, Jed Mercurio’s Bodyguard, peaked at an unconsolidated figure of nearly 11 million viewers. Subscriber numbers only underline the message that traditional viewing methods are being left in the wilderness. Streaming helped see off Blockbuster (which was in its pomp long before my time), and now it’s gunning for cable TV.

So, given the success of their business model, and their almost hypnotic grip on consumers and enormous market share, Netflix should be running to the bank, right? And they are, as $16 billion of revenue would suggest; I’m not about to set up a JustGiving page for them. However, their financial performance probably isn’t being maximised due to an act many of us are guilty of committing: sharing accounts. Why pay for your own subscription when there are no consequences of using a friend’s or family member’s for free instead? In the world of public economics, this is known as the free-rider problem. Although there are limits on the number of devices that can be registered to one account, one individual’s use of the service doesn’t generally affect the access of another person to the platform’s content.

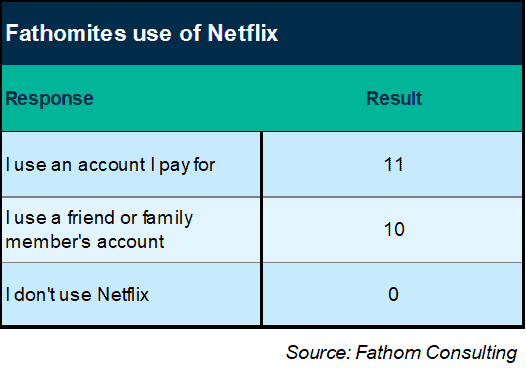

This is a widespread problem for Netflix, and one they’re now trying to clamp down on. If this is a punishment for years of abusing the system, then perhaps it’s fair (although I’m not sure many of you would agree with me siding with the multi-billion-dollar corporation). As a bit of fun, I surveyed my fellow Fathomites about whether they currently pay for their own Netflix subscription, or if they simply use a friend’s or family member’s account. The results are summarised below:

An almost 50-50 split (with no one free of the Netflix stranglehold) — perhaps that explains the insistence on anonymity from some of my colleagues… Still, this shows that 48% of my colleagues aren’t paying for Netflix, significantly higher than the estimated 9% of users that share streaming passwords according to an industry-wide survey by Magid; a low proportion of users, but potentially over $100 million in revenue from the US alone nonetheless. The survey also outlines how these results differ by demographic, with millennials sharing passwords 35% of the time, compared to 13% of baby boomers. Not the first time that millennials have found themselves in the spotlight, although as a Junior Economist who pays for his own subscription, I personally feel pretty vindicated. Meanwhile, this isn’t the first instance of free-riding in the Fathom offices either, as a colleague’s intriguing TFiF explained. Tea anyone?

So, outside of simply raising subscription prices, how could Netflix stop their free-riders chilling at zero cost? In a more conventional context, government intervention would be a viable suggestion, although I don’t think ‘taking back control’ is going to mean universal Netflix access (unfortunately for an honest, paying customer like myself). As with the moral trade-off between watching another episode and a rational sleeping pattern, incentives will play a vital role in any solution to account-sharing at a consumer level.

However, Netflix will continue to hold all the cards due to its position as a low or zero marginal cost company. The brand-building sacrifice of short-term revenue isn’t just effective, it’s also sustainable from a business perspective. As in the case of the sleep-deprived consumer viewing another episode, the marginal cost to Netflix of providing this content on their digital platform is also negligible or potentially non-existent. The result is that even if Netflix is failing to maximise revenue in the first instance due to free-riding, this behaviour is not incurring any significant cost, mitigating any significant marginal impacts on the company’s financial performance and enabling the process of driving out rival providers to continue. Consequently, when the time horizon is broadened and market power is achieved, any subscription income gained from a stricter paywall in the future is almost entirely profit. With this in mind, the immediate concern of free-riding might not be a concern at all, rather an effective marketing ploy.

Returning to Netflix’s ability to outmuscle the competition, more formally this low marginal cost status enables Netflix to forgo higher profits in the short term in order to enhance the net present value of their operation — and that trade-off is improved by the prevailing low interest rate environment. All firms face this choice at all times, trading off short-term pain for long-term gain: low rates mean the long-term gains are discounted by less right now. All firms are being encouraged to delay gratification, so the separating factor will be who can delay for the longest. Those will be the largest, with the deepest pockets, and the lowest marginal costs. Netflix is well-placed — its only real challenger in those terms is bankrolled by Jeff Bezos in the form of Prime Video. While all firms are being encouraged to delay gratification, that can’t be a winning strategy for all of them! They can’t all dominate the market in the long term, or even survive in that market — at least, not without help from the regulators.

So the consumer benefits greatly from the emergence of streaming, while Netflix is able to cash in on their advantage at a business level. However, is this scenario likely to change over time now that Apple and Disney have joined the party? You’ll have to wait longer than five seconds for answers this time.