A sideways look at economics

We’ve all done it. Endured the chaotic cesspool that is the Tube, inevitably encountering that person who refuses to move down the aisle when the train is busy, leaves their backpack on, and blocks the doors when you finally decide you can’t take listening to their awful taste in music anymore. So, are we thinking rationally when we opt to use the Tube?

Rationality is one of the key assumptions underlying neoclassical economic theory. The theory contends that economic agents have objectives, which they attempt to maximise. In the case of individuals, they try to maximise their satisfaction (or utility), whilst producers vie to maximise profits.

Arguably, Herbert Simon’s idea of bounded rationality is a more reasonable assumption. This notion highlights the fact that economic agents don’t always act rationally, meaning that they often end up making satisfying decisions, rather than optimal ones. For example, individuals suffer from choice overload; they don’t make optimal decisions when faced with a surplus of options. For chocoholics like me, this is a relatable concept!

Since Simon received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1978, the sphere of behavioural economics has become increasingly relevant. Challenging conventional thinking is core to what we do here at Fathom, and behavioural economics does just this. It underlines the prevalence of cognitive biases when individuals make decisions. For instance, individuals often use the rule of thumb principle when making decisions, whereby they employ methods that work well in general, as opposed to spending time and effort to understand the nuances of every problem that they face in life.

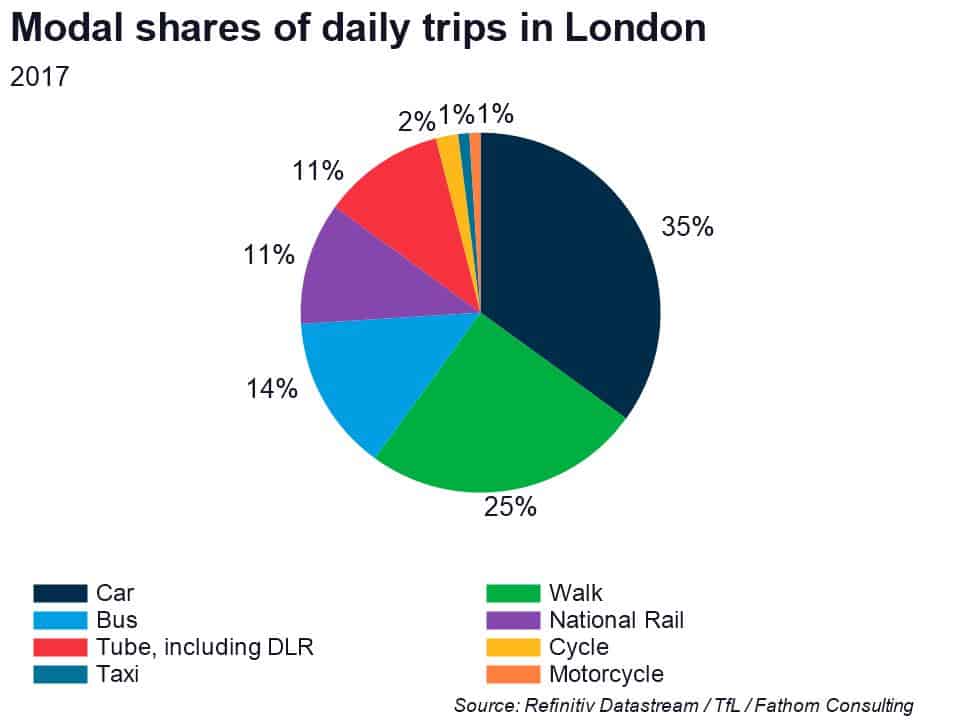

Using the Tube could be an example of herd behaviour — individuals are acting in a certain way just because lots of other individuals are doing the same. There are many alternative modes of transport such as walking, cycling, driving and so forth, and the Tube may not be the best option for everyone. However, you’d be hard-pressed to find a Londoner that hasn’t used the Tube recently.

Herd behaviour is ubiquitous, but there are other examples of irrationality that are particularly apparent in the transport space. Evidence suggests that habits play an important role in determining where individuals choose to stand or sit when they’re on the Tube. This phenomenon can be explained by the status quo bias; individuals prefer to stick with decisions made previously. Even though a certain position on the Tube may be extremely stuffy and overcrowded, individuals still decide to stand or sit there.

Another interesting phenomenon observed on the Tube is that when individuals have to stand during their journey, they tend to stand near the doors, rather than in-between the seats. One environmental psychologist, Richard Wener, has attempted to explain this behaviour. He thinks that individuals stand by the doors to feel a sense of control over when they leave the train. However, this is clearly irrational thinking, since passengers can’t control when the carriage doors open nor how long they stay open for — this is the driver’s domain.

Individual irrationality is commonplace. I often make irrational decisions, such as deciding to buy bread from my local corner shop, rather than walking a little further to the nearest supermarket where I can buy the same loaf of bread for a fraction of the price. I try to rationalise my decision by convincing myself that I do it for the purpose of convenience, but nonetheless, I realise that this isn’t a rational thing to do, even after factoring in the value that I attribute to my time.

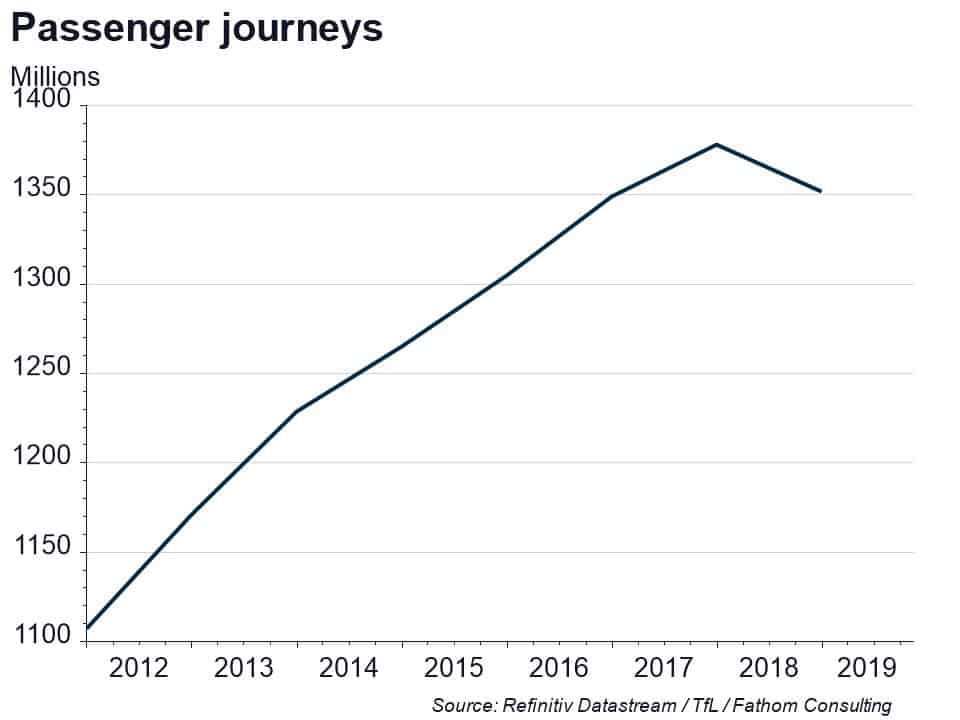

Despite this, Londoners may finally be recognising their irrationality, as fewer journeys were made using the Tube last year than there were in 2017, bucking the consistent trend increase in the number of passenger journeys.

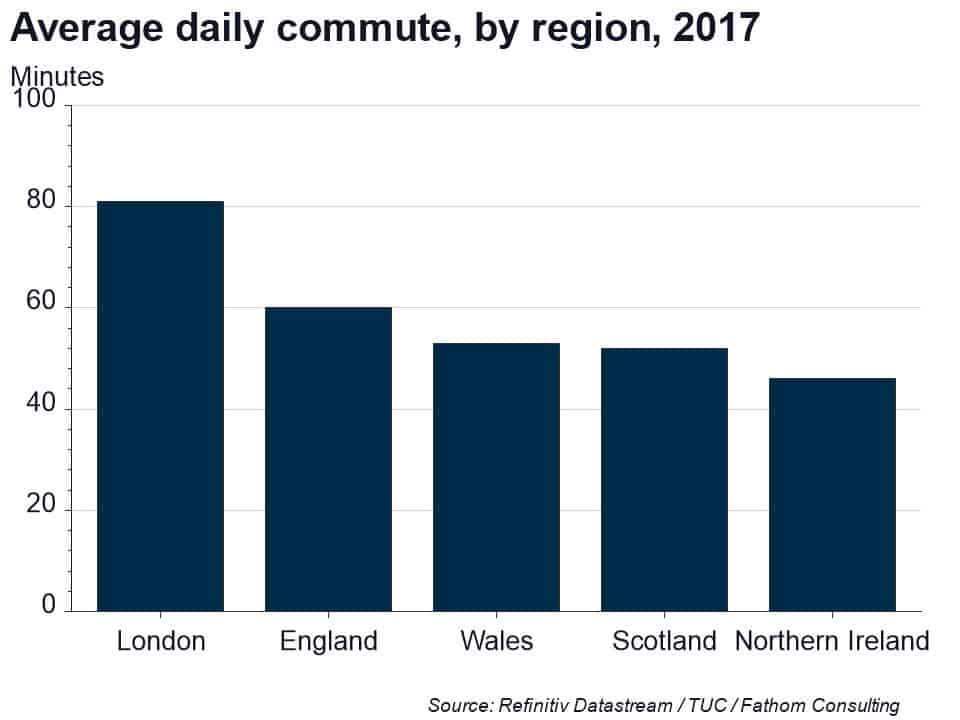

The average journey time on the Tube is 26 minutes, so it’s no wonder that only 11 per cent of daily trips in London are made using the Tube. (Spending five minutes on the Tube is bad enough!) The average daily commute for people living in London is 81 minutes, which is 21 minutes longer than the average across England. Spending 81 minutes on the Tube doesn’t bear thinking about.[1]

Lastly, I recognise that people need to get to work one way or another, so if you do decide to use the Tube, you may as well enjoy the ride as much as possible by securing a seat. How, I hear you ask? One social psychologist, Stanley Milgram, found evidence which suggests that individuals are more likely to let you have their seat if you don’t give them an explanation as to why you want the seat. So, if you want to get the best seat on the Tube, simply ask someone to move. And don’t tell them why!

[1] British attitudes to commuting were analysed in an earlier TFiF by Andrea Zazzarelli: https://www.fathom-consulting.com/an-italian-perspective-on-the-british-commuter/.