A sideways look at economics

Small Island is a new show at the National Theatre based on Andrea Levy’s 2004 novel. A moving production, it tells the story of Jamaican migration to post-war London, highlighting how life for the Windrush generation wasn’t what they expected. Living conditions in the ‘Motherland’ were a disappointment, a fact made worse by the less than enthusiastic welcome they received from parts of their new society. Today’s would-be migrants face similar risks. Nonetheless, millions still opt to leave their country of birth each year. These flows provide economic benefits: principally to the migrants themselves and the places they move to, but also to their home countries in the form of remittances, or cash transfers sent back. It’s not just emerging economies that receive a windfall.

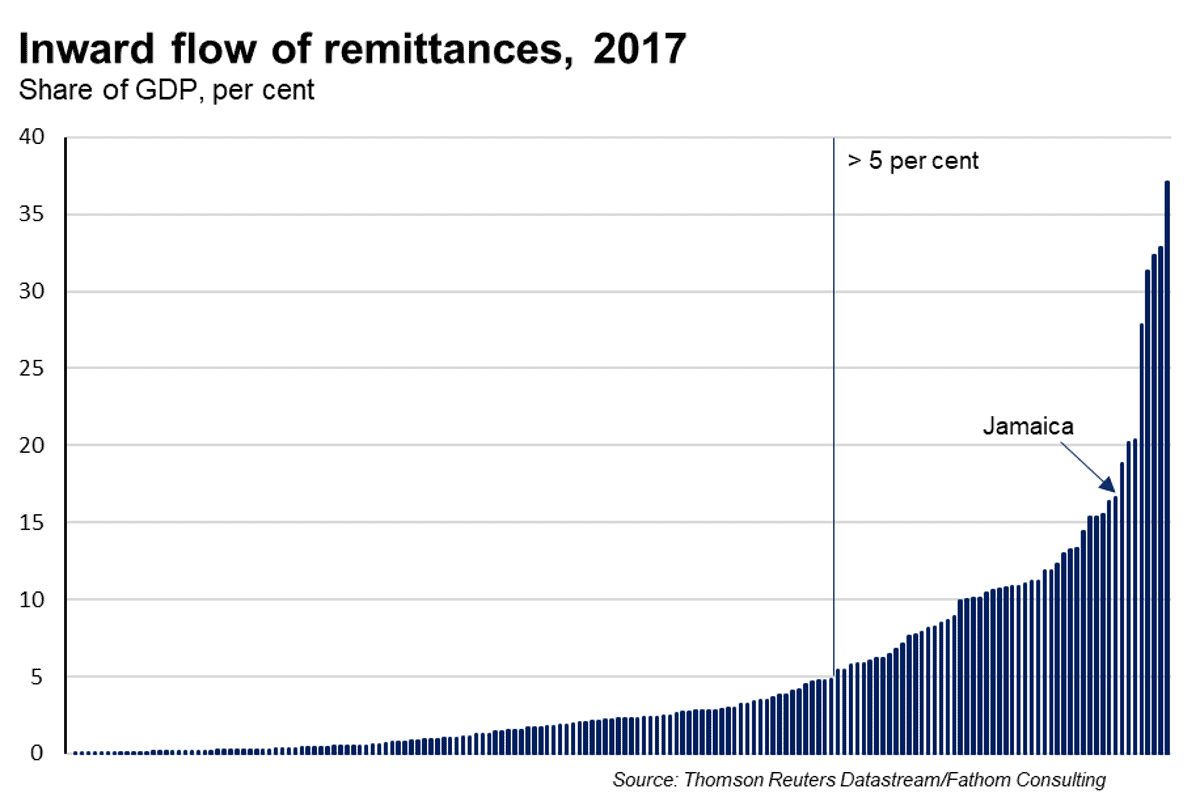

Jamaica benefits economically from people who have ties there but live abroad. Its diaspora is estimated to be around three million, roughly equal to the country’s population. Despite seeking a brighter future, many have taken Bob Marley’s words to heart, and not forgotten their past. In 2017, cash transfers from the rest of the world into the island totalled a staggering 17% of GDP. That figure was the ninth highest among the 171 countries for which we have data. Jamaica is not entirely unique. Remittances are important to many economies. In 52 countries, these flows amount to more than 5% of economic output.

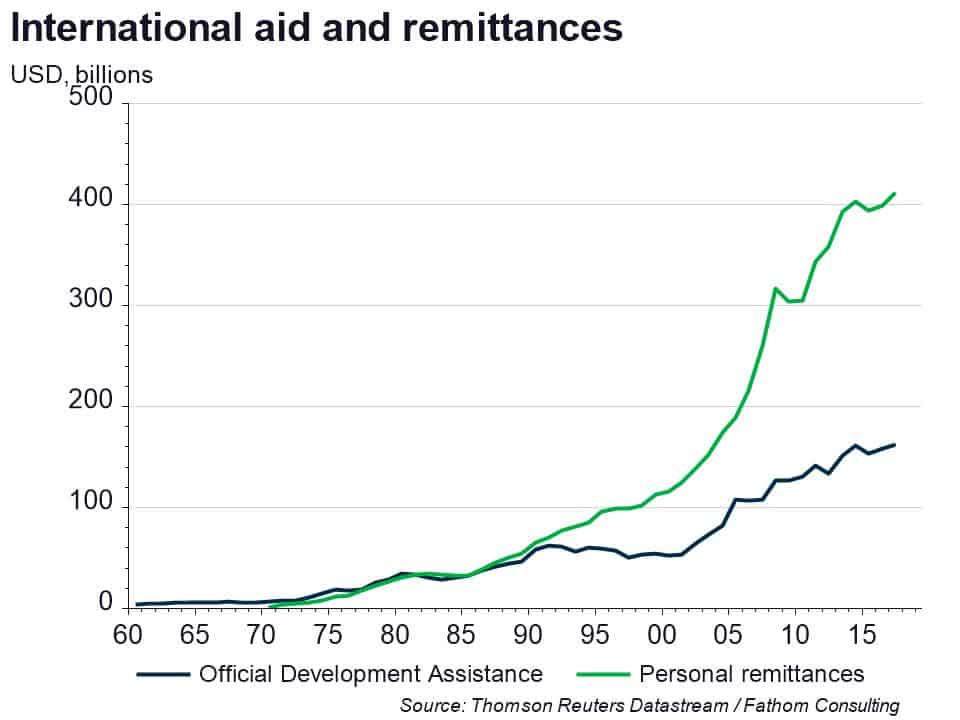

It’s not surprising then that remittances are now seen as a powerful tool for economic development. They broadly tracked the flow of Official Development Assistance (ODA) until the 1990s, but have since outpaced them by a significant margin. As of 2017, international remittances were $412 billion, a figure 2.5 times larger than the flow of ODA. Recognising their importance, the UN’s member nations included reducing the cost of sending money across borders as an official target under the Sustainable Development Goals, with the aim of lowering the average fee from 7% to 3% by 2030.

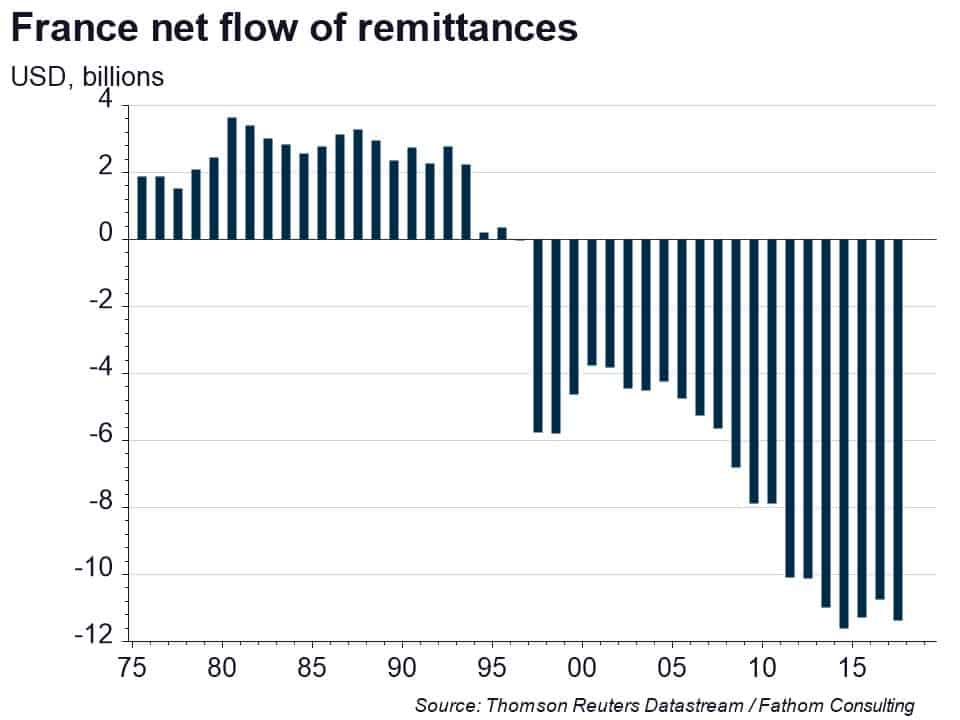

The standard narrative is that cash flows from rich advanced economies to poor emerging economies, but the truth is not so clear-cut. Of the 28 current EU members, 17 are net recipients of transfers from abroad. While Poland and Romania’s position on this list won’t surprise many, France’s might. France first became a net recipient of transfers in 1996. And the gap between outflows and inflows has widened significantly since then. There are 1.5 million French citizens officially registered as living abroad, with 350,000 thought to be living in London. The vast majority of these emigrants are of working age, perhaps attracted to more business- and tax-friendly environments available abroad. These so-called exilés may have chosen to make their money elsewhere, but they still send some of it back to the old country. At 1% of France’s GDP, these flows are not insignificant.

While countries, both in the Caribbean and across the Channel, benefit from cash transfers from abroad, they would probably benefit even more from fewer people leaving in the first place. Departing workers reduce the pool of potential labour, and probably average levels of productivity too, given that they are often better educated than average. In Jamaica’s case, preventing emigration could be achieved by improving average income levels, which remain among the lowest in the region.

Meanwhile, France might convince more people to stay by making it a more attractive place to do business. Leaders in both countries are on the case. Jamaica’s government has set up a programme called Glo-Jam in order to encourage its diaspora to invest back home. If successful, the Jamaican Prime Minister estimates that it could double the country’s GDP. Meanwhile, President Macron has made no secret of his desire to lure financiers and tech firms to Paris. One country’s loss is another’s gain. In the meantime, London will continue to benefit, whether in the form of Caribbean creatives or French entrepreneurs.