A sideways look at economics

On 7 December we’re hosting a conference at which we will call for a major shift in the stance of monetary policy, globally. Here’s why.

Twenty-one years ago, I was an official at the Bank of England, which had just gained operational independence as a consequence of the election of Tony Blair’s New Labour government. The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) had been launched, and the NICE decade (Non-Inflationary, Continually Expansionary) was well underway. Our concerns at the time related to the emerging Asian economies, and trying to understand whether a crisis in those economies would ripple around to the developed world.

The Bank was a wonderful place to work. I remember having spoken to my mum, before going up to university, and asking her how to handle my time there. She said:

“Savour it, because it’s probably the only time in your adult life when you will be surrounded by intelligent, intellectually curious people, thinking about the same things you’re thinking about. The rest of your career will not be like that.”

She was wrong: the Bank was like that too (and so is Fathom, incidentally). Collegiate, intellectually stimulating, and on the cusp at that time of a new paradigm for the UK: independent central banking. And the building itself was (and is) quite a thing — pompous and grand, it felt good walking in through those heavy bronze doors. You could feel the weight, physical and historical, of the place. The pink-liveried footmen. The bullion yard. The vaults. The five-storey canteen, including the heavily subsidised bar that was open only to Bank staff and only during working hours… And most of all: the work, and the people I was working with.

I helped produce the Bank’s inflation forecast, which was ultimately intended to reflect the ‘collective’ view of the nine-person MPC. Once a quarter, the culmination of my efforts, along with those of all the other staff in the Monetary Analysis area of the Bank (and indeed in other areas too) was a presentation by Bank staff to the MPC. This was known as the ‘pre-MPC’ as the decision on monetary policy took place the following day. Pre-MPC lasted for a full day. In those days the venue was the Main Oak Room, a grand, oak-panelled affair with an enormous baize-covered table. The MPC sat at one side of the room, facing the Bank staff arranged in teams around the table.

I have vivid memories of those meetings: Willem Buiter strolling in half an hour late (or more), taking his seat on the panel, and proceeding to roll a cigarette, light it, and rock back in his chair blowing smoke rings at the ceiling, as one of the Heads of Division rattled on about developments in our thinking about broad money over the last quarter. Mervyn (now Lord) King attempting to waft the smoke away, as he grilled the labour market team manager about the accuracy of the earnings data. (All of this directly underneath a large red “No Smoking” sign.) DeAnne Julius disputing the properties of the Bank’s workhorse macroeconomic model, eliciting drumming fingers and twitching jaw muscles from Mervyn. Charles Goodhart sonorously intoning his opinion about inflation expectations, indicating with his tone of voice and inimitable capacity to speak as it were de haut en bas that, once he had declared on the issue, no other point of view could be remotely worth listening to. Sushil Wadhwani delicately but relentlessly dismantling an argument about the information that could be gleaned from financial markets. Happy days.

The meetings were stressful, especially if you were called upon to speak (which was rare for junior staff like myself). And they were inevitably packed with point-scoring by MPC members against each other; and by Bank staff against each other (with one Divisional Head who shall remain nameless memorably stating “I’ll just focus on the parts of this that are relevant for monetary policy: I’ll leave the rest to [another Head of Division, who will also remain nameless] as it’s his area”. Obviously, if something was not relevant for monetary policy, there was not much purpose talking about it in that context, which was the speaker’s point exactly).

But the meetings were also proving grounds for us, with all the drama that entails.

For Bank staff, if you wanted to get on, you needed to make your mark in those meetings. But you obviously needed to choose your moment, and to understand what kind of input was deemed helpful and what was not. The stress arose, for me, much more because of the latter point than the former. I’ve never had a problem making my voice heard. But I did have a problem understanding the small-p politics of that institution: specifically, the importance of the hierarchy. I thought all the formal deference and the pomp was just for show, that surely it couldn’t really matter… But it wasn’t just for show, and it did matter. It took me a long time to see that.

In one of my annual appraisals, my boss told me:

“The thing about you, Erik, is that you’re a free thinker.”

I thanked him. He told me it was not intended as a compliment.

On another occasion, I was told that I was being considered as a candidate to write an important paper on monetary policy. But:

“The trouble is that if we give it to you, you’re going to try and find the truth, right? You’ll go back to first principles and everything. And we’re not sure that’s the right approach.”

My stress arose from not understanding what people wanted, if it wasn’t those things. It ultimately led me to leave the Bank. If these people don’t want me to think, what do they want? Why did they hire me in the first place?

Ten years ago, the global economy was reeling from the impact of the biggest recession in eighty years. Fathom had a strong view that the severity of the downturn called for extreme measures — not just fiscal and conventional monetary loosening (which had already occurred), but unconventional measures too. We felt the Bank of England and other policymakers around the world had badly mishandled the period ahead of the crisis and were in danger of compounding that error in the aftermath. We also felt that it would be interesting to bring some of the drama of the pre-MPC meetings into the public view.

So we hosted what we called the Monetary Policy Forum (MPF). The concept was a conference at which Fathom staff would set out their views for discussion by a panel consisting of former MPC members in front of an invited audience, with plenty of time for an open Q&A at the end. In our first conference, the panellists were the four original external members of the MPC mentioned above. The difference was: Fathom staff definitely think freely, as do the members of the audience, and we are disposed to express those thoughts freely too. The MPF would be like the pre-MPC, only with staff and guests who held and would express their own views without fear.

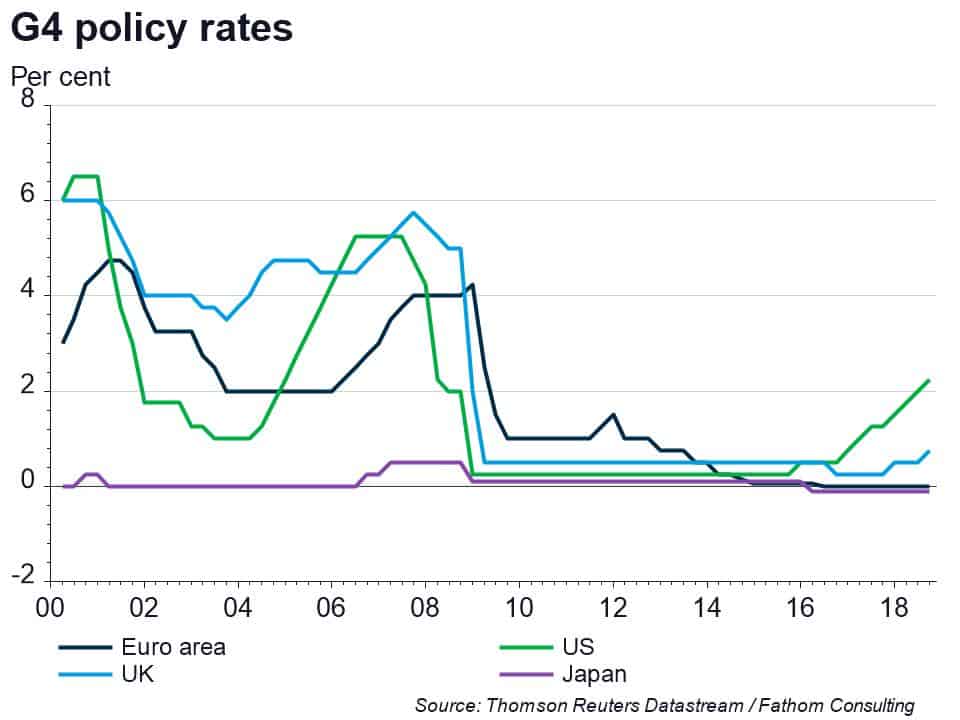

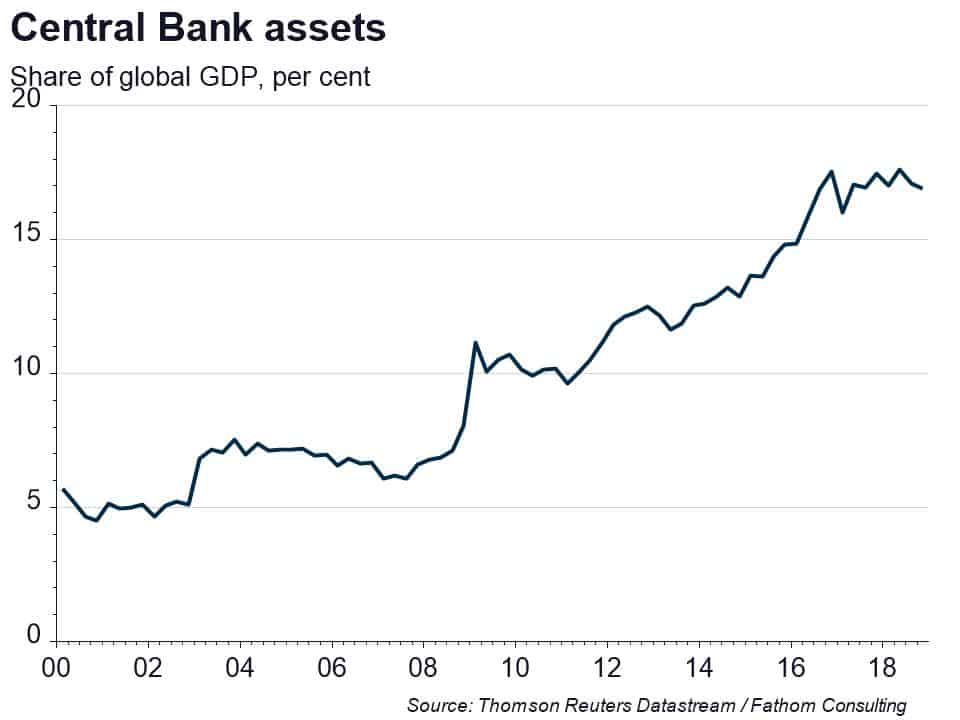

Scroll forward ten years to today. We have hosted a quarterly MPF since that inaugural event of February 2009 — during a highly unusual period for the conduct of monetary policy globally. ZIRP and QE have been in place right across the developed world over that entire decade.

Now it is time to change course, in more ways than one. Ultra-loose monetary policy is doing more harm than good — as we will demonstrate at the conference on 7 December. This conference will, with a neat symmetry, be the last in the quarterly series — and at it, Fathom will call strongly for the removal of QE and reversal of ZIRP. In future, we will host annual conferences at which monetary policy will be one of the issues we address, but not the only one.

Just as the microscopic focus on monetary policy has now run its course, so has the efficacy of monetary policy itself. The shift to independent central banking was aimed at stabilising inflation expectations — in which aim it has certainly succeeded. But an unintended consequence of that success is that policy has now been loosened to the maximum degree possible (and held there for ten years), without any discernible impact on inflation, and even less on inflation expectations. The last ten years have provided a real-world experiment assessing whether shifts in the stance of monetary policy can have long-term real effects, if they are left in place for long enough. Does changing a nominal concept (the policy rate, for example), change the value of real concepts in the long run (GDP for example)? A positive result would violate one of the central tenets of the New-Keynesian/New-Classical synthesis that has dominated macroeconomics during my lifetime: that the classical dichotomy (between real and nominal concepts) holds in the long run.

The evidence points pretty firmly to the conclusion that it does not hold: persistent ultra-loose monetary policy damages productivity in the long term. That is the theme of the next, and final, MPF.

At the conference on 7 December, our panellists will include two former Deputy Governors of the Bank of England, Sir Charlie Bean and Rachel Lomax, as well as one of the most vocal proponents of tighter monetary policy over recent years, Andrew Sentance.

Come along: see what all the fuss is about.

Click here to view the event invitation.