A sideways look at economics

In A Theory of Justice, the American philosopher John Rawls proposed a “veil of ignorance” to help assess the morality of policy choices. The reason? Individuals are biased by self-interest, so their favoured politics risk being unjust. If people had to devise a social contract under a veil of ignorance, without knowing anything about who they would be or what talents they would have, then their choices would be fairer. For example, slavery would find it more difficult to get a foothold in a society where half the population was randomly selected for enslavement at birth, than in one where members of a certain minority group were born as slaves. A modified version of Rawls’s concept would be to ask someone which single attribute they would pick before being born, without knowing anything else about their future self. Such an experiment should help shed light on which traits are most valuable. The choices could include things such as academic ability, industriousness, or place of birth. Objectives matter. Those motivated by economic factors, who have dreams of footballing success, could do worse than opting for place of birth, and choosing France.

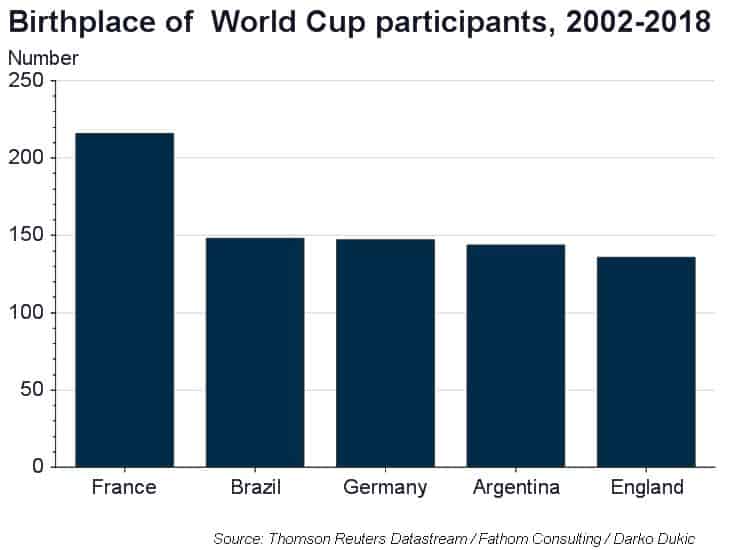

By now, it’s old news that France won the World Cup. Many millions around the world tuned in to watch les Bleus defeat Croatia 4–2 in the final. Almost as many have seen pictures of President Emmanuel Macron celebrating that victory by dabbing with Paul Pogba. What might be less widely known is that France also came top in a different category: it produced more World Cup players than any other country. There were 50 French-born footballers at this year’s tournament, more than double the 23 allowed per national squad. Rather than importing players, as some have controversially claimed, France was actually the World Cup’s top exporter of them. Players born in France represented teams where they have a “clear connection”, including Argentina, Morocco and Portugal. This wasn’t a one-off. Since 2002, France has produced more World Cup participants than any other country. Among metropolitan areas, Paris comes top too, with its banlieues the childhood playground of superstars such as Kylian Mbappé. Darko Dukic, who compiled the figures above and has the enviable task of studying such things, pins the success of France’s football factory on its history of inward migration and its top-class football academies.

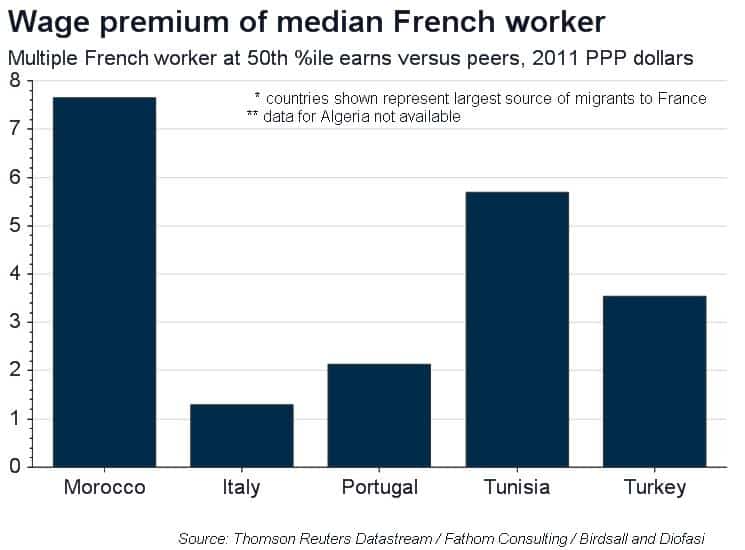

Being born in France may raise the likelihood that you’ll appear at a World Cup. And that same accident of birth substantially increases the chances of having a world-leading pay packet. The median income in France is $43,500 (2011 PPP dollars), which compares to a $1,050 figure in bottom-ranked Madagascar.[1] Of the 144 countries for which we have data, only ten enjoy higher median incomes than France. According to the UN, around 3.5% of the world’s population is a migrant, defined as a person living in a country other than the one they were born in or are a citizen of. For the vast majority of people, their place of birth, more than anything else, will influence where they fall on the global distribution of income.[2] Previous Fathom research has identified how differences in GDP per capita help to explain intra-EU migration. They surely motivate extra-EU migration also. For example, someone at the fiftieth percentile of Morocco’s income distribution would increase their living standards sevenfold by moving to France and maintaining their same relative position.

The stars of the French football team have had to combine natural talent and a lot of hard work to get where they are. But it’s almost certain that the same group of individuals would have had less success if they’d been born and raised in Tonga, which sits bottom of FIFA’s global rankings. By the same token, French train drivers can thank the location of their work, rather than supreme motor skills, for the improved living standards that they enjoy compared to their counterparts in Vietnam. How to assess this from a justice perspective is a question for philosophers. For what it’s worth, Rawls felt that differences in wealth and opportunity among nations reflected different choices about work and saving so should not be seen as unjust. Nonetheless, those born in France — whether aspiring strikers or striking drivers — can consider themselves lucky in many respects.

[1] Anna Diofasi and Nancy Birdsall, ‘The World Bank’s Poverty Statistics Lack Median Income Data, So We Filled In the Gap Ourselves’, Center for Global Development, 2016.

[2] For more, see Branko Milanovic, Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, Harvard University Press 2016. Milanovic finds that more than two-thirds of the variability in global income is determined by where you live — something he terms a ‘citizenship premium’.