A sideways look at economics

In a two-part BBC documentary aired last year, a classroom of seven-year-olds were asked who, out of the boys and girls, would perform best at the funfair game, Strongman. The aim of the game was to slam the mallet down, hitting the base hard enough to send the puck sky-high and the bell ringing. All the children recognised that this was a strength-based game, with the girls picking the boys and the boys picking themselves as the most likely winners.

The reality: no gender was decisively better than the other, with a girl (!!!) scoring 10 out of 10. At that age (pre-hairy chests and broken voices), there’s no biological reason to suppose that boys would be stronger (duh).

The perception: the children were already adopting highly-differentiated views on gender attributes across the board, not just with respect to relative strength, some of which were equally flawed. The girls described themselves as pretty, while it was suggested that boys were smarter, better at being in charge, and more likely to be successful.

This perception is shared by other children of that age that I’ve subsequently quizzed, even though the reality is often starkly different: in terms of relative ‘smartness’, for example, a higher proportion of women tend to be enrolled in tertiary education globally, and – in the UK at least – tend to achieve higher grades throughout their schooling. However, as is increasingly well publicised, that achievement gap turns on its head later in life. Men, on average, progress further, in terms of both seniority and pay.

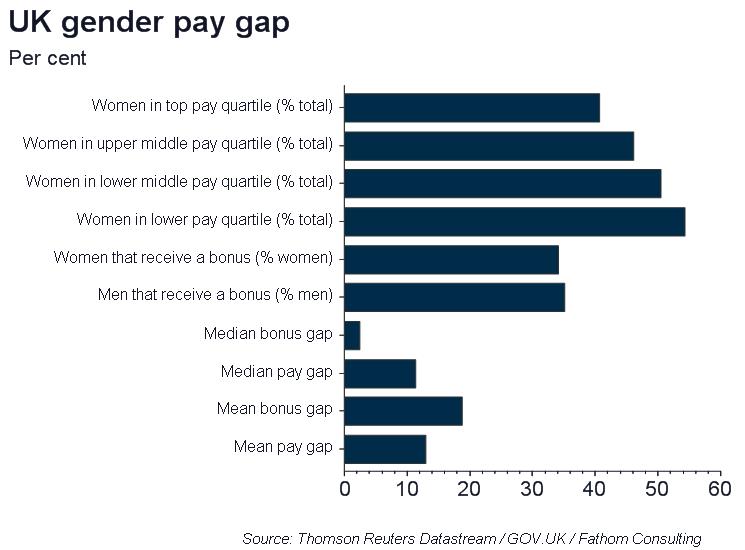

As of next month, companies in the UK with 250 or more employees will be legally required to publish data on their gender pay gaps, which should help illuminate the size of the problem. At the time of writing, more than 2500 businesses have submitted their data, which suggest that men account for nearly 60% of earners in the top quartile, with the dominance of women in the lower quartiles dragging the average female salary down and contributing to an hourly pay gap between men and women of around 13%.

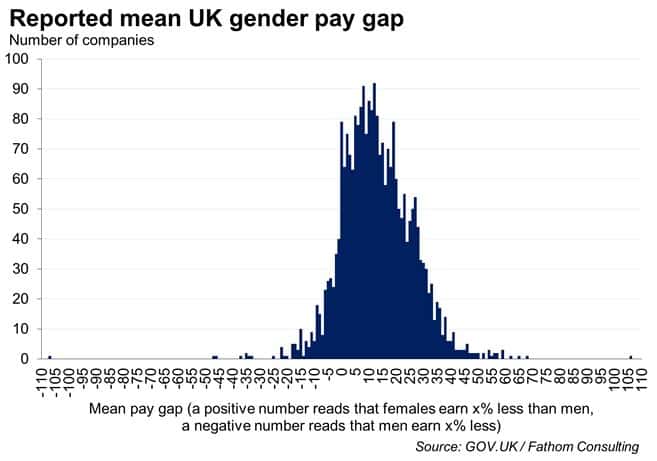

In some instances, including women’s fashion brand Phase Eight, women earn less than half the hourly wage of men. And as the chart below highlights, only 12% of companies, those that sit below zero on the x axis, pay women more on average! Reassuringly though, the average proportion of men and women that receive a bonus is similar at around 35%, although that isn’t the case across the board, with what appears to be large divergences in the bonus structure of some companies. It should also be noted that an implausibly large number of companies claim to have no wage gap, while at least one reports the impossible – a positive gap of 106%.

The pay gap between men and women is particularly glaring in the film industry – media headlines frequently highlight gender disparities. Indeed, using data from Forbes, we estimate that last year’s pre-tax earnings of the top ten actresses as a share of their male counterparts amounted to just 35%! Could this be because women are under-represented in movies? Why wouldn’t a lead female role have the same value as a lead male role, and therefore be paid the same?

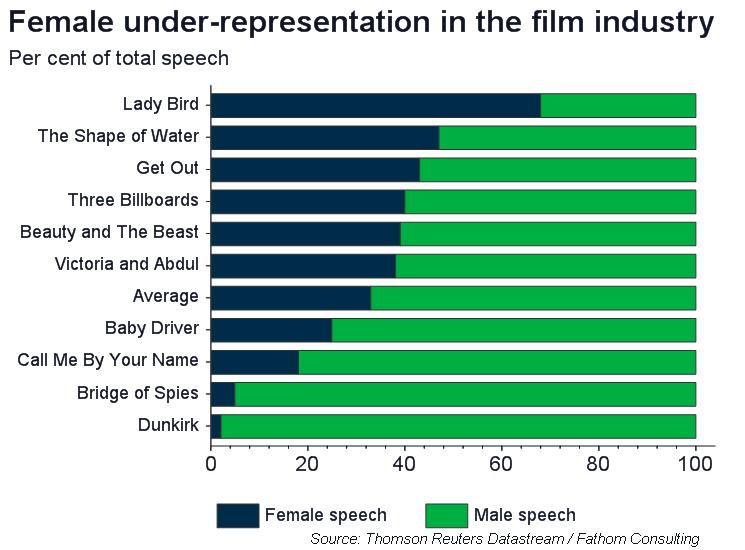

In a bid to find the answer to that question, the team at Fathom Consulting selflessly set about watching a variety of Oscar-nominated movies,[1] from edge-of-your-seat dramas like Dunkirk, to The Shape of Water, which proves that in 2018 a relationship between humankind and fish can be a romantic and beautiful thing! What we discovered, after filling sheets upon sheets (and in one case the back of a Tesco receipt) with tallies, was a marked difference between female- and male-apportioned speech,[2] with the latter dominating.

This was even the case for films with a lead female role, such as Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, which is about a mother’s radical response to the lacklustre police investigation of her daughter’s murder. In fact, of the nine movies assessed, Lady Bird was the only exception to the rule, with its female stars accounting for just under 70% of the spoken content.

Interestingly, films with a larger share of women in the production crew tended to be more evenly balanced. Although, given those films centred around female characters, causation is unclear. At the other end of the spectrum, with men dominating both the conversation and production, were the films Dunkirk, Bridge of Spies and Call Me By Your Name.

That aside, on average across the films analysed, we found that female speech accounted for 33%[3] of the total. That number is remarkably similar to the aforementioned figure on relative pay implied by the Forbes data. This is an interesting finding. In the acting profession, there’s a huge gulf in pay between speaking roles and non-speaking roles – the former typically being protected by unions and the latter not – even if only one word is spoken. Moreover, there’s a branch of the economics literature that assesses the impact of cultural endeavours.[4] The aim is to get at the role of a cultural event or institution in sparking life in a fertile new field.

Measures that look at the market impact miss this point – they would, for example, judge Harry Potter 7 to have had a greater impact than Harry Potter 1. In market terms that might be correct, but in ‘cultural’ terms it would be hard to accept that finding. So other measures are looked at: counting the number of spin-offs in the regular or in the social media for example. At its heart, this is a question of volume: counting the quantity of text that each cultural innovation generates. (Note that it’s the quantity that matters, not the quality: so press coverage along the lines “the latest exhibition by [insert conceptual artist of your choice here] is an abominable waste of time and of public money that would be better spent improving public lavatories” is text, and counts equally as a measure of the cultural impact of that exhibition as the same number of words in a glowing review!)

The sheer quantity of words matters: at the very least as a reflection of an unequal reality and, conceivably, as a contributing factor in maintaining that inequality. In other words, for the film industry, could narrowing the gender pay gap be as simple as giving women more of a voice? Maybe there’s a deeper truth there, too, for the whole of society.

1. To remove any danger of selection bias, films were picked at random, with a few readily-available options added to the mix so as to avoid lonely cinema trips.

2. Sign language included.

3. This broadly fits with the findings of other related studies.

4. See for example NESTA, ‘Five Principles for Measuring the Value of Culture’.