A sideways look at economics

It has long been recognised that some members of the animal kingdom are able to vary the fertility of their species depending on climatic temperature (if you’re interested, look up ‘temperature dependent sex determination’). This effect is typically thought to be evident only in reptiles and fish, but according to research published last month by Kasey Buckles, Daniel Hungerman and Steven Lugauer, it may be that humans have achieved something remarkably similar¹. Picked up by Monday’s edition of the Financial Times, and subsequently reported elsewhere in the UK press, this groundbreaking study found that the number of conceptions in the US was a good leading indicator of US economic activity. Intriguingly, the authors found that US fertility declined sharply several quarters ahead of the Great Recession of 2008-09 – a recession that many economists failed to spot until it was well under way. Humans, it would appear, raise or lower their reproductive rate according to the economic, rather than climatic temperature.

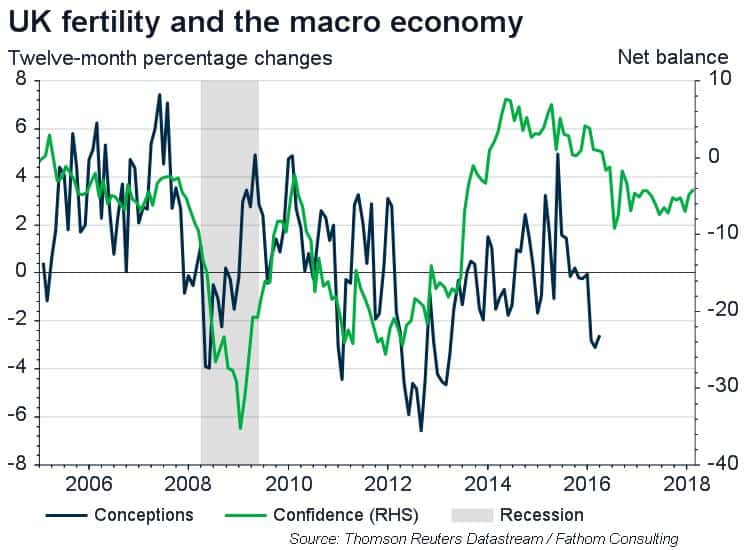

As regular readers will be aware, Fathom is gloomier than most when it comes to assessing the UK’s near-term economic prospects. Indeed, we see around a 50% chance that the UK suffers a recession at some point this year. Should we be adding a measure of UK fertility to our list of things to watch? Maybe. Our chart compares the rate of growth of conceptions with consumer confidence. It seems that the rate of growth of conceptions leads consumer confidence by around two months. Notably, the twelve-month rate of change of the number of conceptions peaked at just over 7% in May 2007. By November of that year, this same figure had turned negative². The UK economy didn’t enter recession until the second quarter of 2008.

Fascinating though this finding may be, as a forecasting tool, its usefulness is limited. Owing to the way in which the data are collected, we can’t hope to measure the number of conceptions until at least nine months have passed! But there’s an additional difficulty, hinted at by our chart. The ONS only publishes monthly birth statistics once each year, and then with a considerable lag. However, this isn’t much worse than the timeliness of the guidance we get from official forecasters, such as the Bank of England or the IMF, who each waited until the final quarter of 2008 before declaring that the UK economy had entered recession six months previously! We’ll keep you posted on any developments via our UK Newsletter service.

1.Kasey Buckles, Daniel Hungerman and Steven Lugauer, ‘Is Fertility a Leading Economic Indicator?’, NBER Working Paper No. 24355 (2018).

2. Others have looked for a relationship between fertility and economic activity in the UK using lower frequency annual data, where the relationship is less clear.