A sideways look at economics

“A person’s name is to that person the sweetest and most important sound in any language.”

Dale Carnegie

The name Kevin was made famous by a fifth-century Irishman, later canonised in 1903. It gained popularity through the twentieth century, peaking in the UK and US during the 1950s and 1960s, but has been in secular decline ever since. In an increasingly globalised world, that may have something to do with its poor reputation elsewhere. In France, the name is associated with work-shy layabouts, while a 2009 study identified bias on the part of German teachers against students named Kevin.

As his namesake, I’m pleased to see Kevin Warsh buck the Gallic stereotype, with a CV worthy of praise. A former Federal Reserve Governor and Wall Street banker, he also happens to be married to a billionaire heiress whose father is chums with President Donald Trump. His impressive career may soon reach its pinnacle. Last week, Mr Warsh interviewed for the role of Federal Reserve Chair, and he’s seen as a leading contender to replace Janet Yellen when her current term ends in February. More than an uplifting story about how a wealthy, well-connected financier managed to overcome the odds and find himself in the Trump White House, his appointment could deliver a fundamental shake up of US monetary policy.

Mr Warsh’s views suggest a radical break from the status quo. Sceptical of monetary largesse, he opposed QE when it was originally implemented, fearing that it would lead to runaway inflation. Maybe those German teachers were on to something after all? But his more recent comments warrant greater merit. He has said that the Fed looks more “asset price-dependent than they look economic data-dependent”. And reports of a private speech he gave last month suggest that he thinks Fed policy has been excessively loose during the post-crisis period. He does not buy Larry Summers’ notion of demand-deficient secular stagnation, and therefore rejects the Fed’s current accommodative policy stance that appears designed to address it.

Investors are taking the prospect of Mr Warsh as future Fed Chair seriously. US Treasury yields rose last week following news of his White House meeting. But can one appointee really make that much difference? After all, there are twelve votes on the FOMC and an unusually large number will soon need replacing, including the Vice-Chair. Surely market participants should focus more on the future overall composition? History suggests not. During the post-war period, no Fed chief has ever been on the losing side of a monetary policy vote.

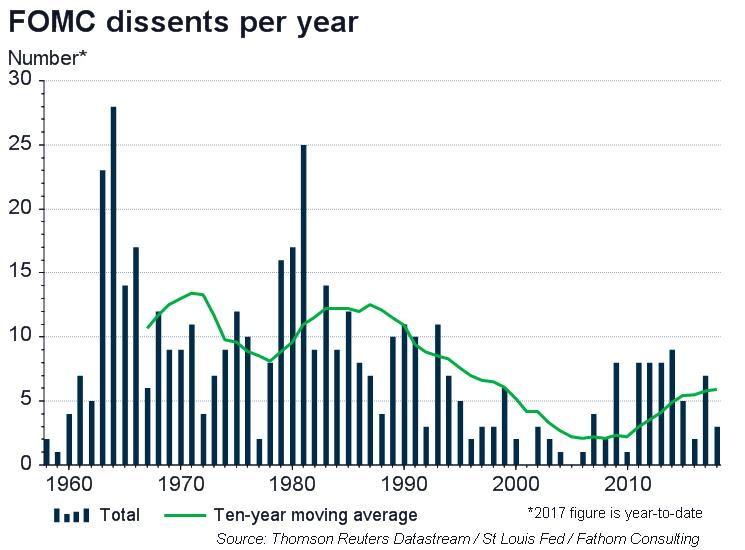

While the Chair has always carried a majority, they have not always carried the entire Committee. The period of near-consensus among FOMC members, witnessed immediately before the crisis, was an aberration. It offers a valuable warning on the dangers of groupthink — a mistake Mr Warsh seems to think is being repeated. Dissents were common throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and seem likely to make a comeback. Big questions remain unresolved about the role of globalisation and technology on inflation, and policymakers have several new policy instruments to manage, including the size of the Fed’s balance sheet and forward guidance. There should to be more to disagree about now than in the past. But does dissent even matter?

Our own prior research shows that dissenting votes at the Bank of England and Federal Reserve rarely end up garnering a majority — a fact that is particularly true stateside. But the past is not always a good guide to the future, as the varying popularity of the name Kevin demonstrates. If Mr Warsh is nominated, and sticks with his decidedly hawkish view once in Washington, investors will have to seriously consider whether will soon see a Fed chief outvoted. The alternative? Too horrible to contemplate: a Fed Chair who continues to carry the FOMC, but who does not get pushed around by markets.