A sideways look at economics

Ever watched a dog chase its own tail?

It’s a thankless task for the dog, but can be amusing for the observer. An exercise in futility always has comedy value, provided it’s carried out by someone else. We shake our heads and smile at the dog’s foolishness.

Next time, though, perhaps we should look in the mirror for a laugh — particularly those among us who make or comment on monetary policy.

In chasing its tail, the dog goes in circles, snarling at, but never quite managing to capture its prize. The harder it pursues the prize, the faster it recedes.

Dizzy from its defeat, the dog dozes, only to continue the folly tomorrow, and the next day, and the one after that, too.

A decade later, and despite its best efforts, the dog will be no closer to achieving its goal. All very frustrating, but, in the broader scheme of things, the exercise probably does it good.

In the dog world, this foolery is without consequence, except possibly beneficial. However, in the world of central banking, there are consequences — damaging consequences.

Through excessively accommodative monetary policy central bankers contributed to the colossal build-up of private sector credit and asset prices that resulted in the global financial crisis. Instead of being punished, their powers were then enhanced, and they were given a whole suite of shiny new weapons to use. Since the recession, they have used the lot, again and again. In pursuit of what? First, avoiding a total, systemic collapse of the global banking system — a vital goal, and one that was (thankfully) achieved.

But what has been their aim since then? They seem to want a return to old-normal growth rates, yields and inflation. A return to the good old days, back out of the rabbit hole that we plunged into after the recession. Unfortunately, that cannot be achieved through monetary policy. In fact, it is monetary policy that took us down that rabbit hole in the first place.

Monetary policy was the problem before the recession, and it remains the problem now. Emergency low rates of interest are encouraging even further accumulation of debt, and weighing on the productive potential of the economy.

But like the dog in our analogy, central bankers have failed to make that connection. Central banks are chasing their own tails trying to fix the problems created by too-loose policy with even looser policy!

For example: do central banks want more private lending, particularly to households, or less? They know that in the old normal, private lending growth was stronger than it generally is now. But they also know that the stock of private lending was too high ahead of the recession, and is too high now. You can’t increase the flow without increasing the stock. Mark Carney and Financial Policy Committee members Alex Brazier and Andrew Bailey have all waged a war of words on lenders. But it is extremely unclear what they want those lenders to do: lend more, or lend less? They warn about complacency and excessive debt, but simultaneously encourage it through low interest rates and a raft of other measures! Quite simply, the problem is closer to home, and not just in the form of low interest rates.

A prime example of this is the Bank of England’s Term Funding Scheme (TFS).

Announced alongside the post-Brexit rate cut, the TFS enables banks to borrow cheaply for four years, with both the price and quantity of that borrowing linked to their lending performance. The aim was to “prevent any perverse effects on the supply of lending from the cut in Bank Rate and help ensure that [the] cut [was] entirely passed through.” So, they do want more lending after all? Perhaps the aim will be clearer when we look at the impact.

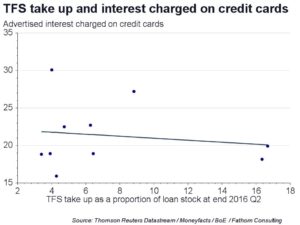

The interest charged on personal loans has decreased, and the Bank reports that the terms on credit cards have become increasingly favourable, such as extended interest free periods. There is also some evidence that banks with the greatest uptake of the scheme tend to offer lower interest rates than their peers, as illustrated by the charts below. Metro Bank is an exception to the rule, perhaps because its clientele is different to the norm and arguably riskier.

But if the TFS has “reinforced the transmission of Bank Rate changes” as intended — then why are Bank staff now busy scolding lenders and warning about excessive credit?

The new normal that we find ourselves in is the result of excessive credit expansion, enthusiastically encouraged by the central banks. They’d like to get back to the old normal. Well, they won’t get there by stimulating further expansion of credit: the faster they run, the further that prospect recedes.

They have already misspent what is — in dog years — almost a lifetime chasing their own tails! It’s not funny any more.