A sideways look at economics

We Brits love to make fun of the French. It’s close to a national pastime. Back in 2008, inspired by news that a trader at Société Générale, Jérôme Kerviel, was suspected of running up losses totalling $7 billion in unauthorised deals, the Daily Mash published a brilliant piece of satire: ‘French trader was forced to work 30 hours a week’. It encapsulates, neatly, everything that we in this country find irritating about our neighbours to the south. Miraculously, not all of these criticisms stand up to closer inspection.

“The French are lazy”, we cry, “they barely work 30 hours a week”. It may be true that the French working week is shorter than ours, but their productivity is higher. Much higher. And not just per hour, but per employee. They produce more, in a shorter space of time. “But the unions. Everyone’s a member of a union over there. They down tools at the drop of a hat.” Actually, at just 8%, trade union membership is less widespread among workers in France than it is in any other major economy.[1]

Emmanuel Macron, together with his La République en Marche! party, enjoyed great success at this year’s presidential and legislative elections, at least in part because of a commitment to implement sweeping labour market reforms. So there must be something wrong with the way the French work, right? Well, yes, arguably there is. But it has little to do with the length of the working week, or indeed trade union density.

Mr Macron wants to make it easier for French firms to fire poorly-performing workers. Present legislation allows dismissal in specific circumstances, but only after a long disciplinary process is followed to the letter. Failure to comply in full can result in unlimited damages being awarded against the employer. Indeed, as an amusing rejoinder to the story above, Mr Kerviel was last year awarded €450,000 by a French court for wrongful dismissal from Société Générale, despite serving a three-year prison sentence for his crimes!

Most economists would accept that, rather than ensuring that a greater proportion of the population are in work, stricter employment protection legislation tends to raise a country’s unemployment rate in the long run. This, at least, is the prediction of so-called ‘search models’. In labour market search models, unemployment is purely frictional. It exists not because wages are set too high to clear the market, but because there are matching frictions, which means that it takes time for firms with vacancies to find suitable people who are looking for work, and vice versa. The harder it is to fire an employee who turns out to be not quite the person the employer thought she had hired, the more certain the employer will need to be that she has found the right match. It will, in short, take longer for successful matches to occur, and frictional unemployment will be higher.

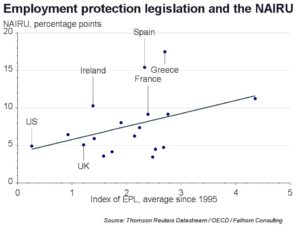

So much for the theory, what do the data tell us? In fact, they are quite supportive. Our chart compares an OECD index of employment protection legislation (EPL), which ranges from ‘0’ for the least restrictive through to ‘6’ for the most restrictive, with that same organisation’s estimate of the NAIRU in 18 major economies[2]. The correlation between these two series is 0.4, suggesting that higher levels of EPL do indeed tend to be associated with a higher rate of unemployment in steady state, though the relationship, unsurprisingly, is imperfect. Other factors are at work.

Our chart also shows a line of best fit. Of all the 18 countries, Greece, Spain and Ireland are the furthest above the line. That is because hysteresis is also an important determinant of the NAIRU. When a country has suffered a long period of cyclically-high unemployment, which is precisely what has happened in all three of those countries following the post-crisis collapse in output, the NAIRU will tend to rise, as people who have been out of work for a long time become deskilled – an effect known as ‘scarring’.

France is quite close to the line of best fit. With an EPL index of 2.4 on the latest reading, our simple regression suggests that France should have a NAIRU of 8.2. In fact, according to the OECD, it is a little above that at 9.2. What if Mr Macron were successful in implementing his reforms? Imagine he is able to cut EPL by a half. Our model suggests that would lower the NAIRU for France by some two percentage points. Were that to be translated into an equivalent fall in the average unemployment rate, as theory predicts, and were the newly-employed French workers to be as productive as those already in employment, that would boost output in France by 2.4%. Every person in France would, on average, be better off to the tune of €800 per year. Were he to do better still, and achieve America’s ‘state-of-the-art’ level of EPL, that dividend rises to €1500 per person, per year. Bonne chance, M. Macron. We wish you well!

[1] We found this hard to believe too. So we checked it very carefully. But according to the OECD it really is true.

[2] We show a long-run average of the EPL in our chart on the grounds that it is likely to take time for a change in the degree of EPL to affect a country’s NAIRU (Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment).