A sideways look at economics

It had to happen someday. After managing to keep its head down for a good few months, Greece is back in the spotlight. By last night’s close the spread between Greek two-year yields and those of Germany had risen by more than 250 basis points since the beginning of the year. The trigger was the publication of the IMF’s latest Article IV consultation with the indebted European nation, in which the world’s lender of last resort argued that the burden of public debt in Greece would rise without bound given any plausible path for growth, inflation and the rate of interest.

Under its own rule book, the IMF cannot extend credit in such circumstances. With a series of elections on the horizon, European heads of state, who represent the only other major creditor, continue to prefer the tried, tested and failed approach of more austerity. But press reports suggest the other euro area countries and the IMF today agreed on a common stance. Markets took heart at the news. Two-year spreads have fallen sharply, reversing more than 50% of their year-to-date rise.

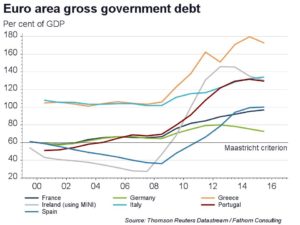

The tussles remind us that the European project is fundamentally flawed – the “E” in Economic and Monetary Union has been ignored. A lack of fiscal transfers means there are no automatic stabilisers. This has caused public finances of the periphery to turn sour. Those who laid the groundwork for the single currency area recognised the importance of sound public finances. Remember the Maastricht criteria? As it happens, this week marked the 25th anniversary of the Maastricht Agreement. Were the tests to be rerun, none of the major member states would now be eligible to join. Even Germany’s debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds the Maastricht criterion by more than ten percentage points. With a debt-to-GDP ratio of almost 180%, Greece would fail by a huge margin. Since Greece joined the euro in 2001, the amount owed by every man, woman and child in that country has risen almost three-fold to stand at some €34,000.

Of course, in its assessment of the Greek public finances, the IMF is correct – just as it was when it first declared, almost two years ago, that the Emperor had no clothes. It was the leak, and subsequent publication of its debt-sustainability analysis in early July 2015 that triggered the first major disagreement between the European Institutions and the Washington-based fund. According to our Financial Vulnerability Indicator (FVI) database, no major economy has yet recovered from such a debt position without defaulting, whether outright, or indirectly through a sharp rise in inflation. Though Japan, in that respect, remains a test case.

We wait for the details of the agreement between the euro area countries and the IMF, but unless it includes substantial debt forgiveness we remain long-term euro area bears.